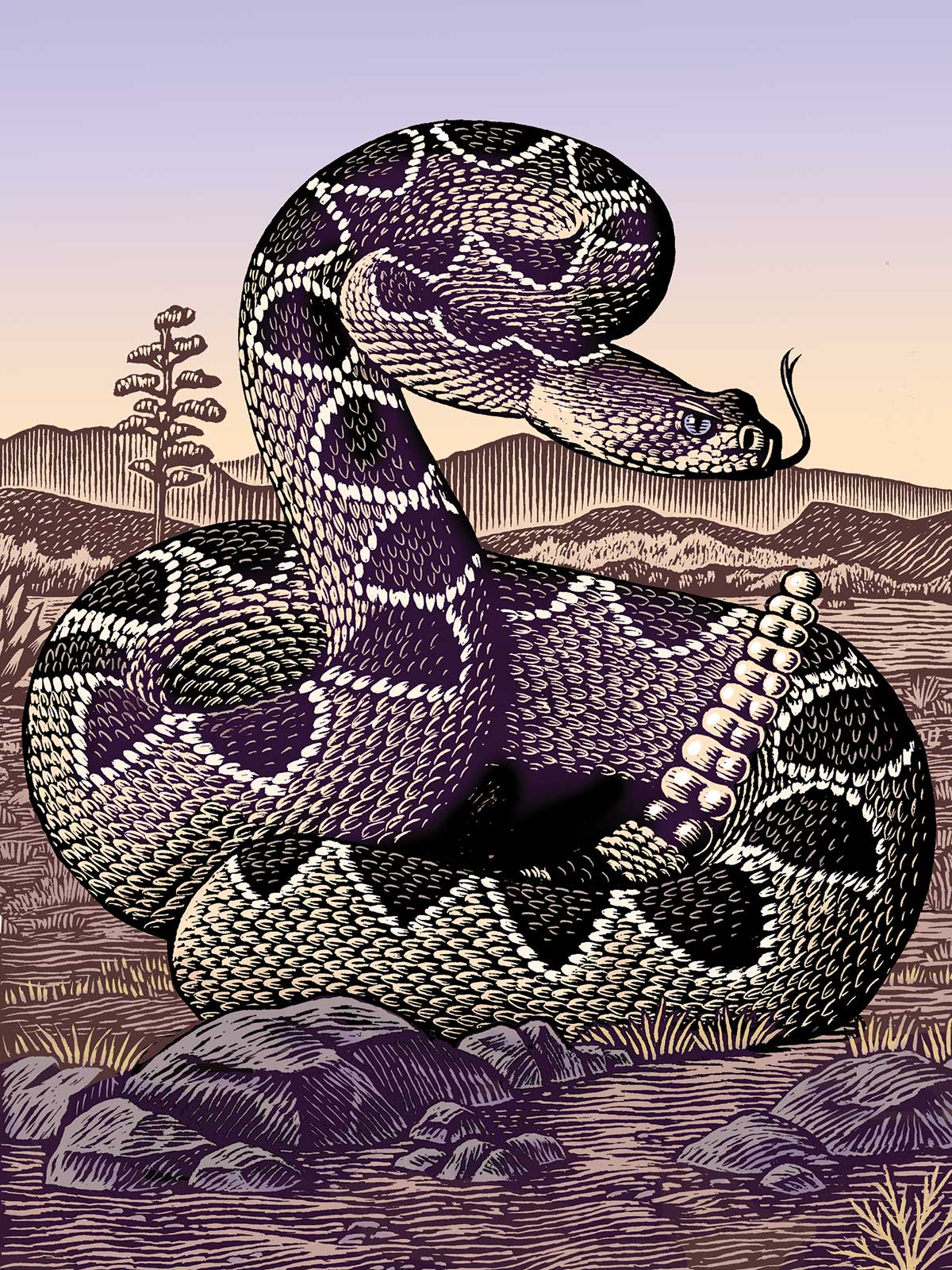

I can trace my love affair with rattlesnakes back more than 60 years to a cool, misty October Saturday morning in the mid-1950s when somebody showed up at the little general store in DeBerry with a very large canebrake rattler in the back of a pickup.

I would have been 6 or 7 years old then, and there was no threatened status as there is now for these shy, somewhat gentle reptiles. In those days, when anybody encountered one, the snake invariably lost a war with a load of No. 6 squirrel shot. This one had succumbed to just such a blast, but it wasn’t his missing head that fascinated me. It was the full-grown fox squirrel that lay in the slit-open belly of the snake. His last meal.

That rattlesnake was absolutely beautiful to me and kicked off a quest that has kept me fascinated for more than six decades. I loved that snake and hated that it had to die.

I wouldn’t see another rattler for at least 30 years. By then I was the outdoors editor at the Austin American-Statesman. I was looking for someone who kept rattlesnakes to allow me to check the efficacy of wading leggings designed to blunt the attacks of stingrays and rattlesnakes.

A Texas Parks and Wildlife Department employee offered a 3-footer, and I placed my right boot down next to the snake. The strike was surprisingly fast, not even registering as a blow against my calf. There were golden droplets of venom hanging off the ballistic cloth of the leggings.

I went several more years without crossing paths with another rattlesnake, but once I hit my stride, I began to see them and hear them more often. I would catch them when I could and pose them for photos in the wild.

I’ve seen them during spring turkey season especially, usually crossing a road or sendero and trying to go on about their business. I’ve literally stepped on rattlers, stepped over them and walked within inches of them as they hid in the brush, usually under a guayacan or other shrubby kind of South Texas bush. Only one of those tried to bite me, a big snake—more than 5 feet long—that fired off from under a bush in South Texas one day. I killed it with a deer rifle, something I’ve always regretted.

Most of the time, rattlesnakes try to stay hidden or move to a hiding place and avoid any contact with humans. In the course of daily life in Central Texas, if you encounter a snake, odds are it will be a western diamondback rattlesnake or a Texas rat snake. But rattlesnakes are not the evil beings of legend and myth in Texas.

Rattlesnake

Mike Leggett

Respect Their Lethal Powers

We are too big for rattlers to eat, and they know that. But they will bite if pressured or frightened, and anyone who suffers a bite from a rattler is in for a tough time.

On average, one to two people per year die from snakebites in Texas, according to the Department of State Health Services, and often, those individuals were handling the snake in some way, either by trying to pick it up or fool with it. Most snakebites in Texas are by western diamondbacks, the most common venomous snake in the state.

Except for the big timber areas of East Texas, western diamondbacks are the most widespread of venomous snakes, with a range covering the area along either side of Interstate 35 and on into the mountains of West Texas. The South Texas desert and the coastal plains are home to very large diamondbacks, 6–7 feet long. Prairie rattlers show up in the grasslands and scrub brush of the Texas Panhandle.

There are no regional differences in aggressiveness or venomous status of the local snakes, which all have the equipment to bite and injure or kill humans.

University of Texas herpetologist Travis Laduc has spent lots of time studying rattlesnakes and the way they bite. Capturing many hours of footage with ultrahigh-speed cameras, he’s learned that the bite itself, from coiled position to contact and back to coiled position, takes but half a second. In that halfsecond, the rattlesnake can deliver a load of hemotoxic venom that works through the bloodstream.

Their Role in the Ecosystem

Rattlesnakes are abundant in most of their natural range, and they are there for a reason. Rats and mice might be stacked a foot deep without rattlesnakes around to eat a few from time to time.

However, I’m not saying you should ignore a rattler in your yard or close to your house where kids or pets might be in danger.

I’ve lost two Labs to rattlesnakes over the years myself.

My wife and I came home one night. As we walked up onto the front porch in the dark and I was trying to get the key into the lock, we were shaken by the loudest buzzing I’ve ever heard—so loud up under the porch I thought it had to be cicadas. However, Rana wasn’t fooled. She was back in the truck in seconds and yelling for me to get in as well.

I climbed into the cab and turned the lights on to illuminate a large rattlesnake lying on the doormat, just inches from where I had been standing moments before. We had cats then, and as outdoor cats tend to do, they had choused that snake until he couldn’t get away and was cornered against the front door.

I had no choice but to do away with the snake. That’s one rule I don’t break: No snakes around the house.

In Central Texas, where I live and where a generous portion of Texas rattlesnakes live, that is kind of a classic encounter.

Maybe you find one hiding in your flower bed one morning or crawling through your corral. We should be thankful for them and for what they do to keep vermin under control.

Here’s a challenge for anyone who comes across a rattlesnake:

Let it stay in its hiding place or just crawl away into the brush. If it’s hiding, rattle or not, it’s just hoping you’ll go on by and leave it to hunt in peace.