On a sunny October day in Elgin, east of Austin, the Hogeye Festival is in full swing. The historic town center, in Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative’s service area, closes streets to make way for a car show, a barbecue cook-off and an art fair along with blues music. The Peterson Brothers—Glenn Jr., 21, and Alex, 19—of nearby Bastrop captivate the audience with classic Texas blues customized with their unique riffs.

The Peterson Brothers are furthering the blues tradition in their own way. “T-Bone Walker is a big influence along with Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, Freddie King and Albert Collins,” Glenn says. “Their sound and even their arrangements, especially live, had lots of things mixed in. T-Bone had some jazz and a little bit of everything mixed in.”

A few months earlier, the Peterson Brothers performed their modern brand of Texas blues at a whole other kind of function, Preserving Historic Texas’ Real Places conference in Austin, addressing the creation of the Texas Music History Trail. The Petersons’ presence at this event is significant: The soulful, indigenous music they play is directly connected to many of the people and places that will be featured on the Texas music history virtual driving tour and specifically to four musicians who poured the foundation of what the world knows as Texas blues.

Bastrop’s Peterson Brothers—Glenn Jr., left, and Alex—have been playing music for about a decade, since they were 12 and 10.

Julia Robinson

Along with the Mississippi Delta, Texas is a seminal source for blues music, which evolved from field hollers first articulated by enslaved African-Americans seeking relief from the drudgery of forced labor and from gospel music in African-American churches, both of which had connections to musical traditions in West Africa.

But Texas blues has a unique sound. “Texas blues is different because of the vastness of the geography of Texas and the different cultural groups that have settled here,” says Alan Govenar, biographer of Texas blues legend Sam “Lightnin’ ” Hopkins. “This cross-fertilization of musical styles includes the Cajun and Creole music of Louisiana, the music of Mexico to the south, and dance sounds lifted from German, Czech and Polish immigrants.”

Thanks to audio recordings dating back to the beginning of electronic reproduction in the 1920s, the trajectory of Texas blues is easy to trace.

It starts with Lemon Henry “Blind Lemon” Jefferson, from Wortham in rural East Texas—the state’s first blues star. His reputation came from a lengthy career playing the streets of Deep Ellum, Dallas’ entertainment district, and on his records, beginning with Long Lonesome Blues and Got the Blues, a 78 rpm disc he made for Paramount Records in Chicago in March 1926.

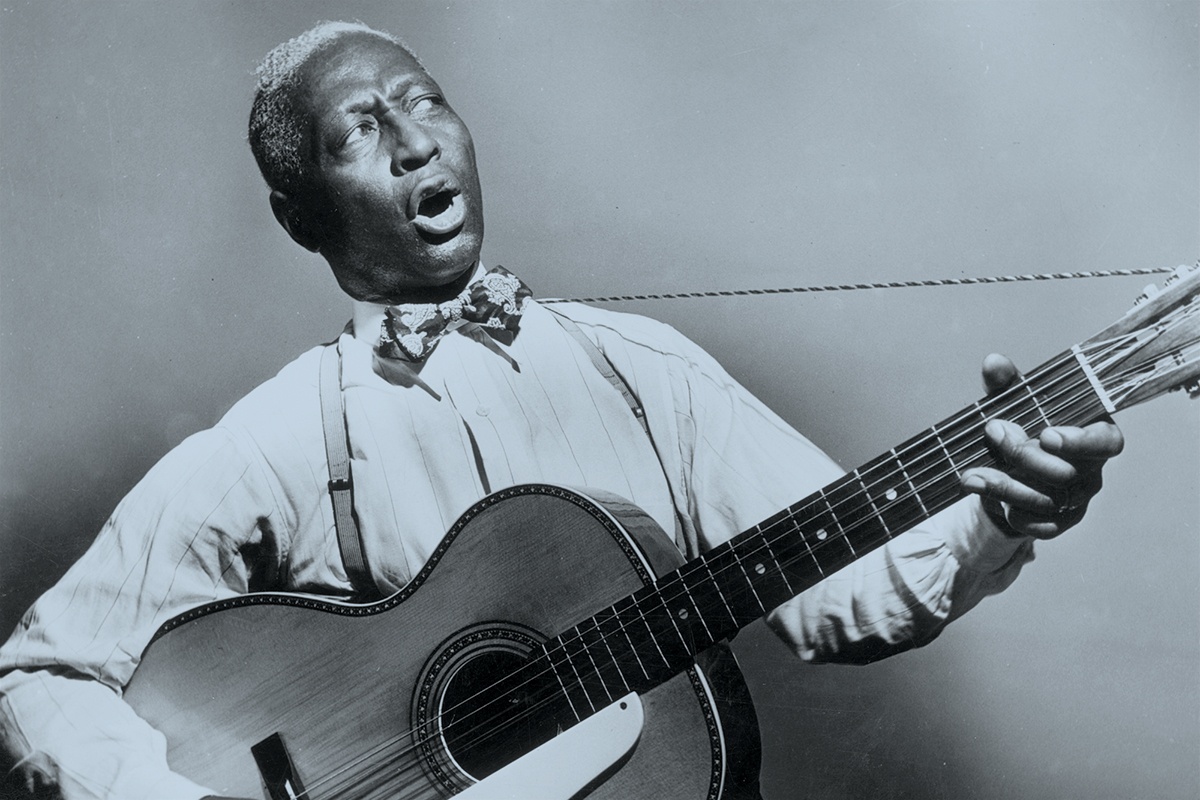

Blind Lemon Jefferson, left, was Texas’ first blues star. Like Jefferson, Lead Belly, right, played on the streets of Deep Ellum in Dallas.

The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

A skilled guitarist and evocative vocalist who expressed his pain with a lonesome moan, Jefferson, born blind, found acclaim by singing songs narrating troubled relationships underscored by loss. He was hardly the only one. According to Govenar, rural Central and East Texas brimmed with bluesmen and -women, many who embraced recording technology and made records. These folks included Henry Thomas from Big Sandy, who played a handmade cane flute he called the quills and achieved fame with songs about railroading; Blind Willie Johnson from Marlin, whose Motherless Children and Nobody’s Fault But Mine continue to get covered; the Houston singers Sippie Wallace, Victoria Spivey and Elvie Thomas, who all enjoyed national fame as recording artists in the 1920s; and Washington Phillips, who constructed and played a unique instrument he called a manzarene that resembled two autoharps welded together.

“The brilliance of the great African-American blues artists in Texas is that their ears were wide open,” explains Bill Minutaglio, author of In Search of the Blues: A Journey to the Soul of Black Texas. “They were listening to these other forms of music and then weaving it in,” he says. “The Texas blues is a sort of international blues, a United Nations gumbo of sounds.”

Jefferson’s acclaim caught the attention of others. Huddie Ledbetter moved to Dallas from his native Bowie County to accompany Jefferson on the streets of Deep Ellum and sang about it. In 1933, the world finally heard Lead Belly, Ledbetter’s performing name. University of Texas folklorist John Lomax traveled to Louisiana’s Angola Prison to record prison field songs. When he heard Ledbetter, who was serving time for murder, Lomax was so taken that he delivered a recording of Ledbetter and an appeal for the blues singer’s release to the governor of Louisiana. After Ledbetter was released from Angola for good behavior in 1934, Lomax hired him as an assistant and eventually became his manager.

Like Jefferson, Lead Belly, played on the streets of Deep Ellum in Dallas.

Hulton archive | Getty images

As Lead Belly’s manager, Lomax exposed him to audiences who embraced the singer as a folk artist rather than as a bluesman. A charismatic multi-instrumentalist who sang songs about work, Hitler, prison, sailors and cowboys, Lead Belly was the first Texas bluesman to travel from the streets of Deep Ellum to perform concerts in New York and Paris.

Soon, Texas blues musicians took the next leap forward by electrifying the guitar. Eddie Durham of San Marcos and Charlie Christian from Bonham are considered the first to experiment with amplifying guitars in the 1930s. “With those big bands, you couldn’t hear the guitar,” Durham said in a 1984 interview with Govenar.

Christian secured a microphone between his knees to boost the volume on his guitar solos. Durham carved out the inside of an acoustic guitar and inserted a resonator made from a tin pan. He also experimented with steel guitars and drilling phonograph amplifiers into the body of an acoustic guitar. “I used to blow out the lights in a lot of places,” Durham said. “They weren’t really up on electricity like they are now.”

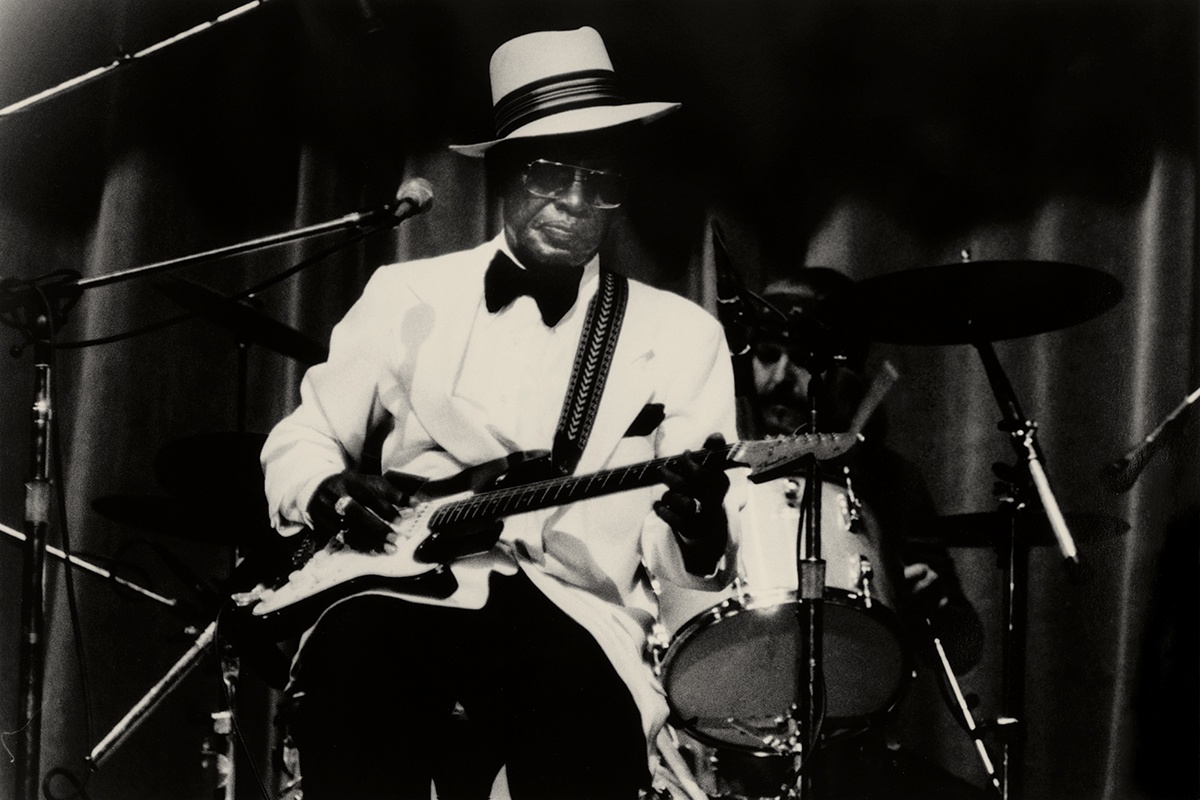

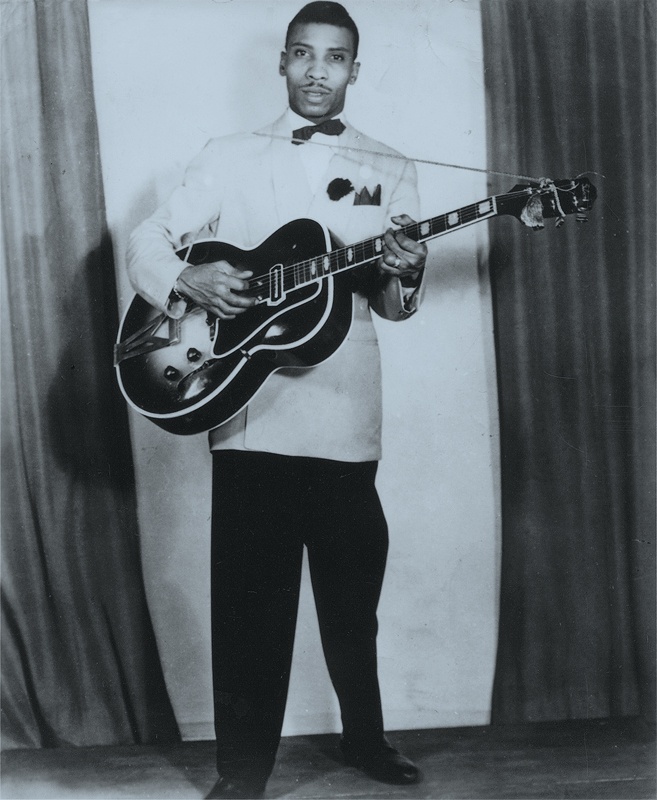

T-Bone Walker is known as the father of electric blues guitar.

Courtesy University of Texas Press

Durham and Christian set the table for another Texas blues player who would become known as the father of electric blues guitar. Aaron “T-Bone” Walker, born in Linden in East Texas, grew up in Dallas’ Oak Cliff neighborhood in the 1910s. Walker’s earliest recordings carry on Jefferson’s traditional guitar style, but when he went electric in the 1930s, he created a brand-new sound. His guitar is “really out front, the engine driving the train,” Minutaglio says. “T-Bone made the electric guitar really cool, and a lot of people wanted to play it after seeing him. You can connect the dots to Keith Richards, Eric Clapton and John Lennon and everybody else that comes after.”

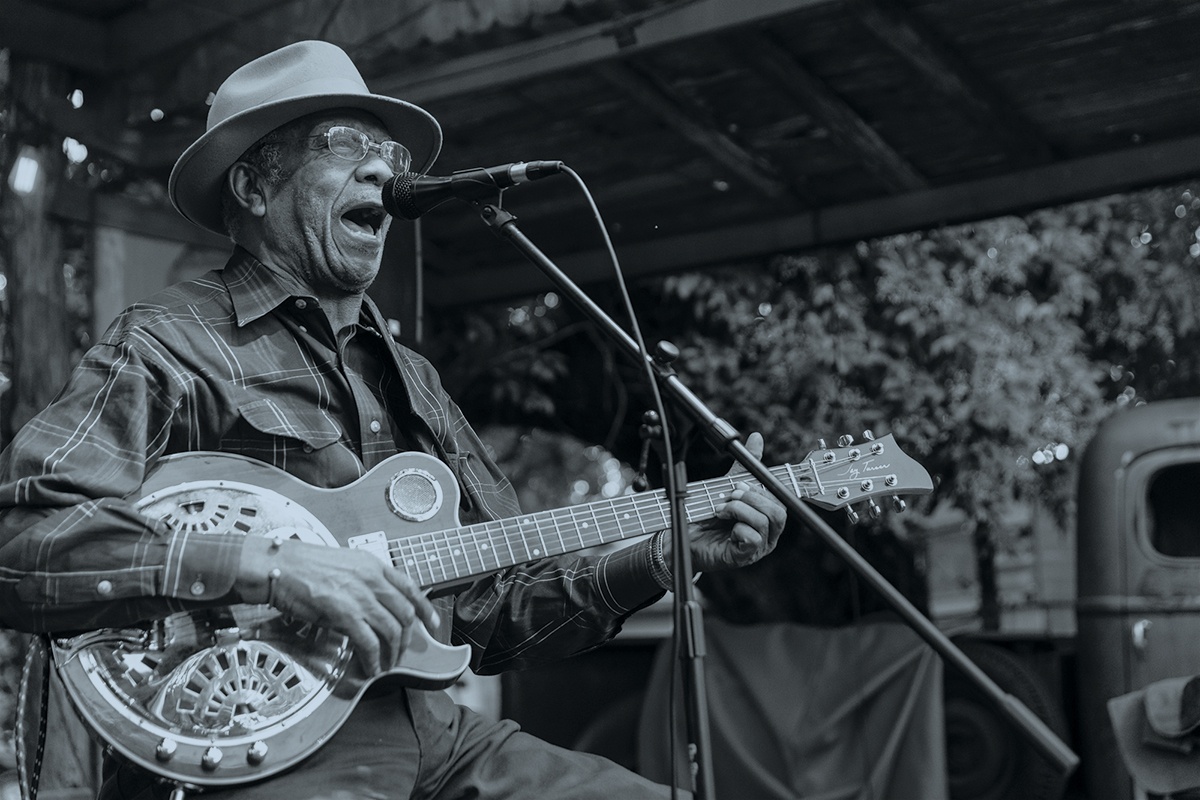

Lightnin’ Hopkins, a singer and guitarist from Centerville, has a Jefferson connection, too. An 8-year-old Hopkins witnessed Jefferson at a church picnic in Buffalo and fell in love with Jefferson’s blues; Jefferson returned the favor by letting the younger Hopkins play alongside him, something he didn’t let anyone else do.

Hopkins played electric guitar but usually solo or as part of a small combo, a marked contrast to the big band ensembles Walker preferred. Hopkins started as a street bard. His original songs were free-associating commentary, often made up on the spot, accompanied by a stinging, jangling six-string sound. “Lightnin’ had this floating encyclopedia of blues lyrics in his head, and he could put them together in different combinations at will, so if you put down the money, he’d make you a song,” says Govenar.

Hopkins moved to Houston in the 1940s and played bars, street corners and city buses. He recorded prolifically, more than 800 songs. Recording engineer Bill Quinn built his Gold Star Studios in Houston, now SugarHill Recording Studios and the oldest continuously operating recording studio in Texas, primarily to record Hopkins.

A parade of notables followed Jefferson, Ledbetter, Walker and Hopkins. Hopkins’ cousin, Mance Lipscomb, helped his Navasota birthplace earn the title, “Blues Capital of Texas.” W.C. Clark grew up singing gospel music in the rural enclave of St. John’s in 1940s north Austin. He now plays his own repertoire of blues, rhythm and blues, and soul songs, combining original music with tunes from B.B. King, Al Green and Otis Redding. Texas blues created Don Robey’s Duke-Peacock recording empire in Houston; the blues soul of Dallas’ Johnnie Taylor and Fort Worth’s Delbert McClinton; the Houston guitars of Albert Collins, Johnny “Guitar” Watson and Johnny Copeland; and the new generation of blues articulated by ZZ Top, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Freddie King, Jimmie Vaughan and the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Gary Clark Jr., and a whole lot more—all the way up to those kids from Bastrop, the Peterson Brothers.

“The blues is our heritage,” Alex Peterson says. “It’s important to keep it going.”

See more of Julia Robinson’s work at juliarobinsonphoto.com.