The Devils River snakes through 94 miles of scenic yet hostile terrain southwest of Sonora. Before the mid-19th century, the river was reportedly called the San Pedro or Saint Peter. In 1848, Jack Hays led a scouting expedition of Texas Rangers and Delaware Native Americans in the region. A story goes that when Hays came upon a forbidding gorge bottomed with water, he asked a native what the river was named. When told, Hays sputtered, “Saint Peter, hell! It looks like the devil’s river to me.”

The name stuck. But did Hays name the river?

Read another account of that conversation, and the details could differ. Or, if you’re like Midland author Patrick Dearen, you may dig deeper and discover little-known information. While writing Devils River: Treacherous Twin to the Pecos, 1535–1900, Dearen studied the 1848 journal of rancher Samuel Maverick, who accompanied the Hays expedition. Upon reaching the waterway, Maverick recorded in his notebook, “Mouth of Devil’s River.”

The earlier date of Maverick’s entry, Dearen believes, challenges the Hays version, later reported in a newspaper. Quite possibly, the men “may have only reaffirmed the name ‘Devil’s’ rather than coined it,” the author theorizes.

Such uncertainty bedevils those seeking to learn how or why the horned hellion came to be a namesake for so many places, plants and points of interest in Texas. Few names can be referenced to a specific source, except perhaps for mentions by folklorists. No matter the origin, the devilish names in nearly all cases hint at a trait or demeanor so unpleasant or vile that only the devil himself must have inspired their creation.

No doubt, topographic features in West Texas were often named after the devil because the land can be so inhospitable, says Dearen, who grew up in dusty Sterling City in West Texas.

“I’m reminded of Ann Kelton, the wife of the late author Elmer Kelton,” he recalls. “A native of Austria, where forests and streams abound, she was shocked when Elmer first brought her to his home near Crane. As she once told me, as they got closer and closer to Crane, she thought she had reached the ‘jumping-off place to hell.’ ”

Hot and dry describe the Trans-Pecos region, where the devil and his Spanish counterpart, el diablo, lurk amid fearsome canyons and rugged mountains.

For a short time, the Diablo Dam and Reservoir existed only in name. That’s because officials of the time deemed the evil connotation inappropriate for a future international lake to be fed by the Devils and Rio Grande rivers. In 1959, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower and Mexican President Lopez Mateos agreed on amistad, Spanish for “friendship.” Amistad Dam was dedicated in September 1969.

Archaeology buffs may know of the Devil’s Mouth Site in Val Verde County. From 1959 to 1967, archaeologists worked to examine the prehistoric remains of a campsite near the mouth of the Devils River before the new Amistad International Reservoir flooded the site. The stratified excavations produced ancient pollen records and stone projectile points called Golondrina.

Ghost stories galore haunt the Devil’s Backbone, a ridge of rolling hills in Comal County. Along a scenic stretch of Ranch Road 32 once promoted as Devil’s Backbone Skyline Drive, a roadside park offers stunning views. In Montague County, another ridge called Devil’s Backbone served as a lookout for Comanches and Kiowas.

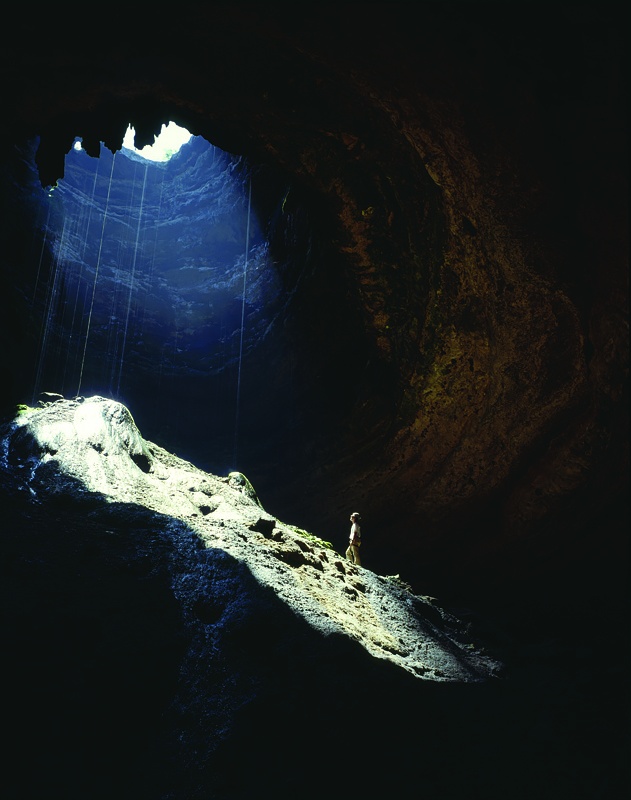

Near Rocksprings, Devil’s Sinkhole State Natural Area protects a gaping cavern that hosts a huge Mexican free-tailed bat colony from late spring through early fall. No one is certain who initially discovered the hole, but a firsthand account credits some pioneer women with naming it in May 1876.

While searching the area for Indians, rancher Ammon Billings and his posse came upon the dark chasm. They invited their wives to see “a helluva hole in the ground.” His wife, Lucinda Billings, later recalled, in a story printed in the Kerrville Mountain Sun in August 1949, that the women, who agreed the hole was impressive, suggested that the less profane name of Devil’s Sinkhole “would do just as well.”

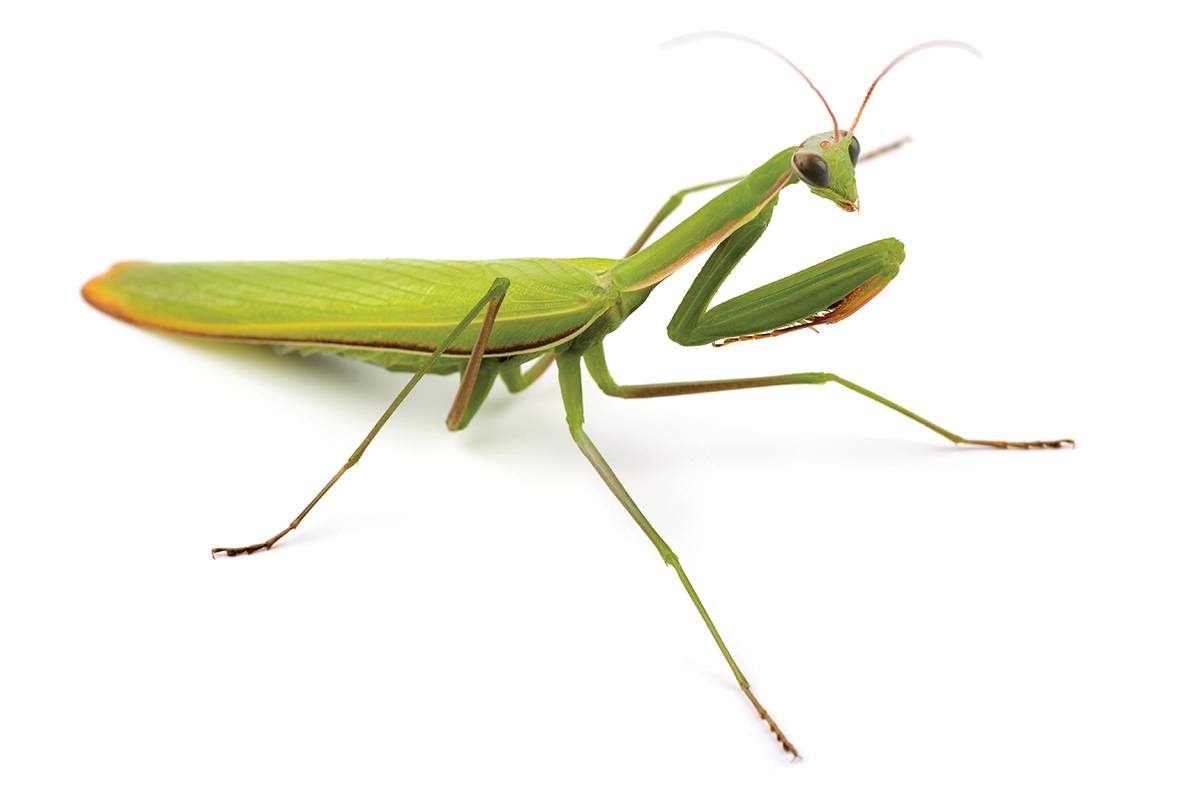

Devilish names once stigmatized a few fauna. Native Americans and hunters called blue jays “devil birds” because their raucous cries alert other animals of danger. According to Texas folklore, the devil’s horse (praying mantis) was poisonous. Thus, a man would go blind if one spit in his eye, and a cow would die if she swallowed one. Another devil’s horse was the scary-looking but harmless walking stick, also once called the devil’s darning needle.

According to A Dazzle of Dragonflies, old-time believers feared another devil’s darning needle, the dragonfly.

Co-author James Lasswell’s grandmother was certain that “devil’s darning needles” were poisonous (they are not) and “told us that if they stung us we would be sick for a long time and might even die.”

In the plant kingdom, the devil also appears frequently. Historical Common Names of Great Plains Plants lists more than 50 species besmirched with diabolical names. Devilwood, also called American olive, is hard to split. Elephant’s-foot, a perennial herb, also goes by the name of devil’s grandmother. Three plants share the name devil’s shoestring. One, commonly known as trumpet vine, spreads aggressively. Another is also called goat’s rue, a silvery plant with stringy roots that contain a toxic substance called rotenone. And one is a grasslike agave that’s also called beargrass.

Devil’s head cactus, also called devil’s pincushion and horse crippler, grows wide but low to the ground, making it hard to spot. On the frontier, cowboys sometimes would slice off a devil’s head and use the level surface to play mumblety-peg, a game typically played with pocket knives that required the loser to remove a peg driven in the ground (or cactus) with his teeth.

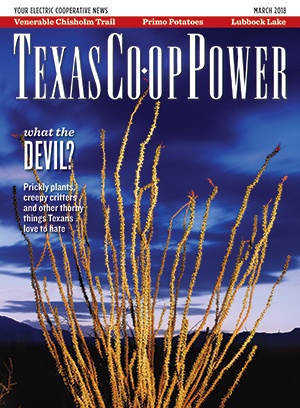

Devil cholla grows in a small region of Presidio County. Ocotillo, a spiny-stemmed, woody shrub of the desert, is also called devil’s walking stick.

Treacherous thorns and prickly leaves arm another devil’s walking stick, a native tree also known as Hercules club and prickly ash. Its creamy yellow flowers attract honeybees and other pollinators. Birds and other wildlife relish its purplish-black berries, which may be toxic to humans.

Devil’s claw refers to the bizarre seedpods of Proboscidea louisianica, a low-spreading, bushy annual with pastel-colored flowers. Its tender, edible seedpods resemble okra. When dried, they split lengthwise into two curved, sharp claws that latch onto furry animals and scatter the black seeds inside.

Devil’s claws serve other purposes. In a December 1888 issue of the Stephenville Empire, a columnist advised young boys to collect and bundle the “common, hooked nuisances” to make Christmas gifts “fit for a king.” Used as toothpicks, devil’s claws “are very tough, do not splinter off, and curve to suit the mouth,” she wrote. Modern hobbyists fashion the claws into sculptures, dream catchers and wreaths.

The town of McLean in the Panhandle hosts an ominous place called the Devil’s Rope Barbed Wire Museum. Inside the brick building, you’ll find a huge collection of barbed wire strands, not to mention posthole diggers, barbed-wire sculptures and antique fencing tools. “When barbed wire began to be used in the 1870s, livestock were not used to it,” explains Delbert Trew, former museum curator. “Because many animals were injured by it, religious people considered barbed wire to be the work of the devil. Hence, the name devil’s rope.”

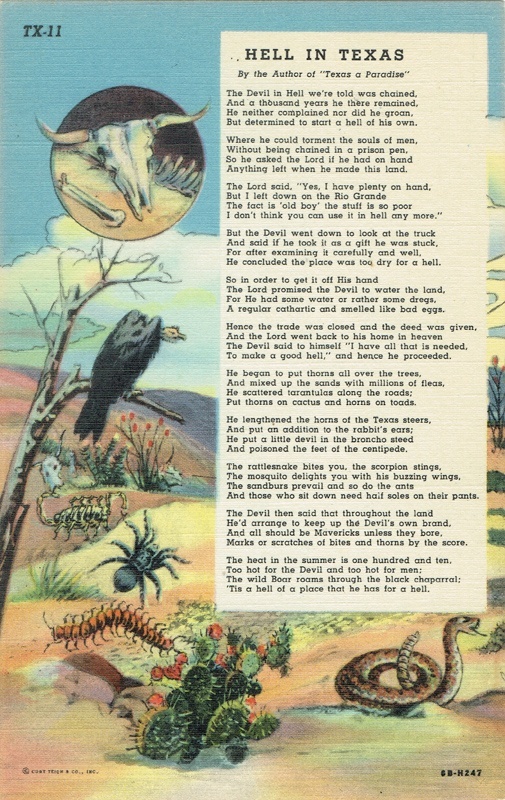

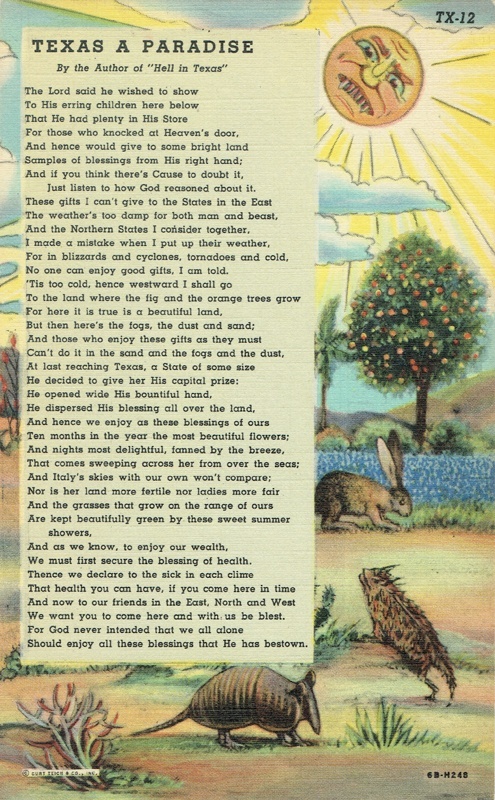

Blistering heat likely inspired Hell in Texas, a lyrical poem that humorously tells how the devil negotiated with God for a plot of land, where he could torment men. As folklore will do, Hell in Texas (also titled The Devil Made Texas) evolved to describe various locales in the Southwest, such as Arizona and New Mexico.

The Best Loved Poems of the American People, published in 1936, reprinted a longer version of Hell in Texas attributed to an “unknown” writer. According to a 1944 Texas Folklore Society publication, attorney E.U. Cook of Iowa, who managed a land and cattle company in Frio County, probably penned the original text after witnessing the effects of a severe drought that lasted from 1885 to 1887. He later returned to Texas during a greener year, which inspired another poem that omitted any mention of the devil.

Its title? Texas a Paradise. But that’s another story.

Sheryl Smith-Rodgers, a member of Pedernales EC, lives in Blanco.