General R.G. Dyrenforth wasn’t a general, and he wasn’t really a rainmaker, nor was he a U.S. commissioner for patents, though he claimed all of these titles at one time or another. Officially, he was known as a “concussionist,” one who makes it rain by blasting water from the sky with explosives in the belief that “rain follows the artillery.” The general must have been pretty convincing because the U.S. government hired him to make it rain by virtue of things that go boom in the sky.

For a little more than a year, starting in 1891, Dyrenforth was seen as everything he said he was, but mainly he was the man who could blast rain from the sky. The notion that such a thing could be done had been around for centuries. Plutarch, in the second century, first observed, or thought he did, that rain followed battles. Napoleon believed it, and so did a man named Edward Powers, a civil engineer who wrote the book on the subject, “War and the Weather,” in 1871. The book detailed how rain generally fell a few days after a battle, but Powers neglected to study the probability of rain at a given site when a battle hadn’t been fought there.

Powers persuaded Congress to invest $2,000 initially to conduct experiments based on the theory. Dyrenforth was chosen to lead the task, and so he sallied forth to—where else?—Texas in the heat of summer.

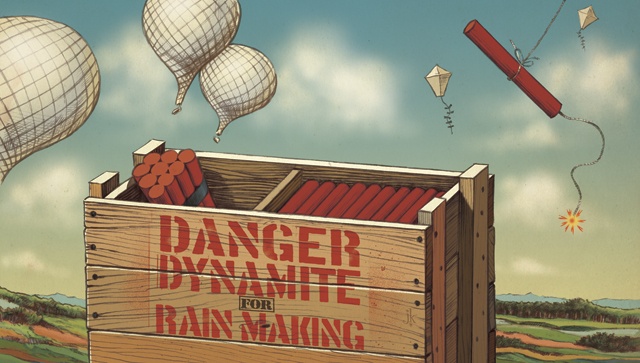

Dyrenforth and his team of fellow scientific novices arrived in Midland armed with boxcars of dynamite, gunpowder, cannons, kites and balloons designed to explode. All of this firepower was directed at the sky: Rain or else! Come out of those clouds or we’ll blast you out!

“I have no doubt that rainmaking will be carried on in portions of the country as a practical thing,” Dyrenforth told The New York Times. “It is certain that rain can be caused by explosion in mid-air. I do not make any predictions as to the general practice, nor am I interested a cent in the question, but, as a matter of cold fact, based on my experiments, I know that rain can be produced.”

Newspapers across the country hailed the experiments as an earth-shattering breakthrough—somewhat literally—in mankind’s never-ending struggle to bend nature to its own purposes. The Washington Post, New York Sun, Chicago Tribune and Rocky Mountain News all reported torrents and gully washers resulting from Dyrenforth’s explosives and gizmos. Of course, none of those papers were located anywhere near Midland; they had to take Dyrenforth’s word for it, and they mostly did.

Two periodicals that did send reporters to observe the experiments firsthand were a couple of agricultural journals, Farm Implement News and Texas Farm & Ranch. The ag writers had a much different take on the proceedings and their results than Dyrenforth’s press releases. They saw a group of people who mostly didn’t know what they were doing, ill and forlorn, watching their gizmos go off at the wrong times and catching all manner of things on fire. Flimsy kites, no matter how well-armed, were no match for the West Texas winds. Scientific American magazine followed up on the ag writers’ reports and deemed Dyrenforth’s experiments “an expensive farce.”

Robert Kleberg of the King Ranch provided some money for Dyrenforth to blast the heavens around his place, and it actually rained there around the time of his experiments. In San Antonio, however, he blew out the windows in a downtown hotel, obliterated a mesquite tree and became an object of ridicule and scorn all over the country. He went back to working in the patent office and made no more news until after he died in 1910 at the age of 66, when his will was revealed.

Dyrenforth, supposedly of sound mind, stipulated that to receive his bequest, Dyrenforth’s 12-year old grandson had to renounce Catholicism; finish high school; attend Harvard, Oxford and West Point; spend six months in the Army; and attend law school in the U.S. when he was through with all that.

The old man might as well have stipulated that his grandson do something really impossible—like fire explosives into the clouds to make it rain.

——————–

Clay Coppedge is a frequent contributor.