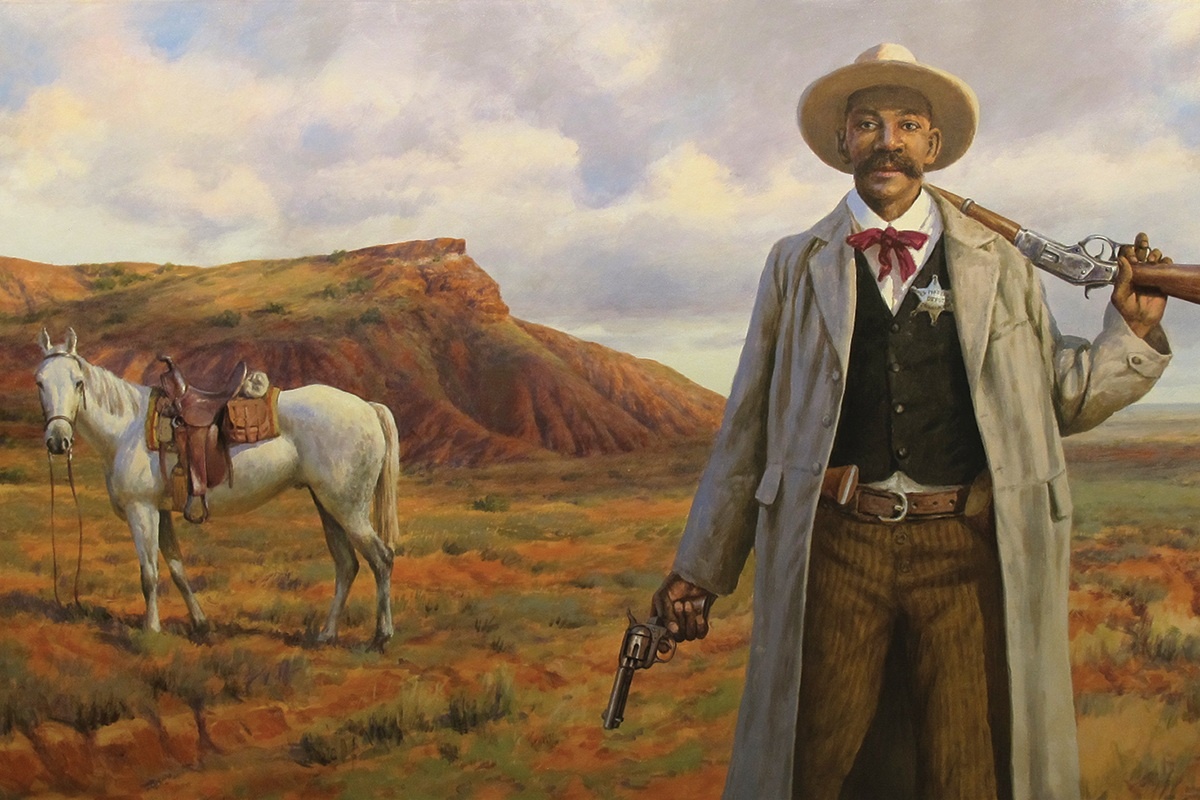

Bass Reeves came to Texas from Arkansas as an enslaved 8-year-old with the William Reeves family in 1846. He would go on to become the first African-American U.S. deputy marshal west of the Mississippi and among the most relentless lawmen of his or any day.

When William’s son, George, went to fight for the Confederacy during the Civil War, Bass was sent along with him. At some point, Bass lit out for Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) and never encountered the Reeves family again.

Bass Reeves found refuge in Indian Territory with the Seminole, Creek and other tribes and later bought land near Van Buren, Arkansas. He married Nellie Jennings, a Texas girl, in 1864 and grew crops, raised livestock and reared five boys and five girls.

In 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant ordered Judge Isaac C. Parker to bring law and order to Indian Territory. Parker authorized the hiring of 200 deputy marshals, and Reeves, an occasional scout and guide for deputy marshals, was one of them. Reeves was big (6 feet, 2 inches) and already a legendary marksman, and he knew the country.

Reeves also turned out to be dedicated and fearless. He worked for 32 years as a U.S. deputy marshal and reportedly brought to justice 3,000 felons, all but 14 of them alive.

Art T. Burton, author of the 2006 biography Black Gun, Silver Star: The Life and Legend of Frontier Marshal Bass Reeves, isn’t sure about that 3,000 number, even though it came from Reeves himself in a 1902 interview. Even so, Burton found many newspaper accounts of Reeves bringing in a dozen or more desperados at a time.

Burton’s lifelong fascination with Reeves began when he was 11. He saw a movie about Wyatt Earp and asked his grandfather if there were any black marshals in the Old West. “There was one,” his grandfather told him. “His name was Bass Reeves.” Burton sought out family members and others who were around during the marshal’s heyday and listened to often-fantastic and nearly always unverifiable stories about Reeves. But once retired as a history professor, he got to wondering if some of the stories might be true, which led him to write the biography.

“He was the baddest of the bad,” Burton says. “He was an expert with a rifle and a pistol. And if you were hiding, he would find you.”

Reeves operated, Burton says, without fear or favor, arresting the minister who baptized him for selling illegal liquor and even his own son, Bennie, for killing his wife. It’s hard to compare him to anybody, except maybe the Lone Ranger. And Burton does make that comparison.

Burton notes that U.S. marshals working in the region at that time, including Reeves, routinely hired Native Americans to work with them, and he found instances of Reeves repaying strangers for their kindness and hospitality with silver dollars. Perhaps that compares to how the Lone Ranger handed out silver bullets to verify his identity.

The original Lone Ranger wore a black mask, and Burton found several accounts of Reeves using disguises to capture bad guys. Many of the desperados Reeves arrested were sentenced to prison in Detroit, where The Lone Ranger radio show originated.

While Burton readily admits there is no conclusive evidence to support the notion that Reeves was the prototype for the Lone Ranger, he believes that Reeves “is the closest real person to resemble the fictional Lone Ranger that we have.”

Of course, there’s also the possibility that the creators of the radio show just made up the character. But Reeves was the real deal. He died in 1910, but, oddly, no one knows where he’s buried.

Burton believes he’s still in disguise.

Writer Clay Coppedge is the author of Forgotten Tales of Texas (The History Press, 2011).