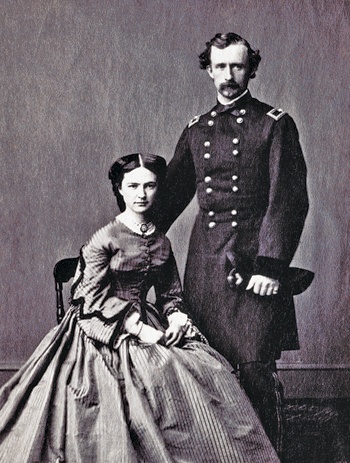

Perhaps it was his curly, blond hair or the rakish red bandana he wore with his uniform that enticed Elizabeth Bacon Custer, wife of Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer, to travel with her husband and thousands of his troops across the Texas frontier in 1865. Libbie, as she was known, gamely endured the hardships to be near her husband. A book she later wrote about her experiences, Tenting on the Plains, is one of the earliest documents of Army life on the frontier told from a woman’s perspective.

When the Civil War ended, Custer, a Union general, was ordered to take command of a cavalry division and march through Texas to squash any lingering Confederate resistance. His volunteer soldiers were understandably irritated because their brethren were going home, and they were not.

“All I knew,” Libbie wrote, “was that Texas, having been so outside of the limit where the armies marched and fought, was unhappily unaware that the war was over, and continued a career of bush-whacking and lawlessness that was only tolerated from necessity before the surrender and must now cease.”

A military ambulance with leather-backed seats that could be flattened to form a bed was repurposed as a traveling wagon for Libbie, but during the day she rode her horse beside the general at the head of the procession. Eliza, Gen. Custer’s African-American servant, was the only other woman who accompanied the troops. Libbie slept in the ambulance at night, out of reach of poisonous insects, venomous snakes and stinging plants. She feared holding up the division’s departure each morning because of the many tiny buttons on her dresses and the difficulty of finding her hairpins in the dark. “Our looks did not enter into the question very much,” she wrote. “All we thought of was, how to keep from being prostrated by the heat, and how to get rested after the march, for the next day’s task.”

Custer “tried to arrange our marches every day so that we might not travel over fifteen miles,” Libbie wrote. “So far as I can remember, there was no one whose temper and strength was not tried to the uttermost, except my husband.”

Libbie and many of the troops suffered the torments of “break-bone fever,” a mosquito-borne disease known today as dengue fever, which caused agonizing muscle and joint pain. Water was scarce, and the scorching sun beat down relentlessly, but Libbie’s positive outlook and joy at being allowed to accompany her husband raised the spirits of all. “The General had reveille sounded at 2 o’clock in the morning,” Libbie wrote. “It was absolutely necessary to move before dawn, as the moment the sun came in sight the heat was suffocating.”

Custer’s trek began in Alexandria, Louisiana. After a stop in Hempstead, more orders arrived in November to move the soldiers to Austin for the winter. The heat gave way to whistling north winds, but Libbie’s determination not to be a “feather-bed soldier” goaded her out of the ambulance each morning where she huddled by the fire until it was time to mount up.

After a three-month march, the soldiers finally pitched camp on a hill above Austin, and Provisional Gov. Andrew Jackson Hamilton offered the use of the Asylum for the Blind, closed during the war, as a headquarters building. The couple moved into a room with three large windows, and the pleasures of getting out of bed on a carpet and dressing by a fire helped to smooth Libbie’s adjustment to living indoors again.

In spite of the cutthroats and villains roaming freely throughout Texas during Reconstruction, Custer’s troops gradually brought order to the frontier. Rumors of war with Mexico subsided, and little by little, civil authorities took over the job. By the end of 1866, Custer was ordered north to await a new assignment.

For the next several years, Libbie would faithfully follow her husband, singing his praises even as he led his troops—and himself—into the arms of death at the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn. After the massacre, she grieved for a decade before sitting down to write her own version of Custer’s story, books that portray him as a gallant soldier, loving husband and brilliant commander. Custer’s image was so highly polished by Libbie’s stories that, although he had many detractors, he is remembered today as a romantic, headstrong hero. Libbie died in April 1933, four days before her 91st birthday, and is buried next to her husband at West Point.

——————–

Martha Deeringer, frequent contributor