Everybody farmed when I was a kid, but there’s just one now,” says Royce Johnson, referring to his son. “I’m grateful Shelby wanted to continue.”

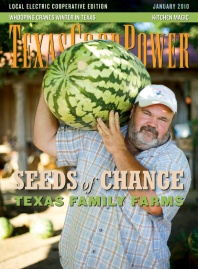

The Johnson family history in farming southwest of Center runs deep, stretching back to the turn of the century before names and particulars are lost to memory. Shelby Johnson, the last in the line of Johnson farmers, is among just a few still farming in Shelby County. His farm, served by Deep East Texas Electric Cooperative, is also the largest in that area in terms of variety and quantity of produce, which includes tomatoes, peas and watermelons. Many community members call him “The Last Farmer.”

“This is what my father did and what his father did,” says Shelby, 40. “I guess it’s a heritage thing.”

Friday, July 17

We’re in Shelby’s pickup truck on the way to the watermelon field for a resupply run. During the peak of harvest season, Shelby might cut this road between the family’s two farm stands, one in town and one on U.S. Highway 96, and the farm a dozen times a day. It’s now mid-July, and the most frantic days have passed. Smashed watermelon chunks litter the sandy dirt road every few hundred feet—casualties of frequent trips in the past weeks. There’s a thud and a squish as the truck’s tire hits one.

“You have to love farming to farm,” Shelby says. “If you do it to make money, I don’t recommend it.” He is quick to point out that while he has had some success, farming has never entirely paid his bills. Like many in the area, Shelby is also an industrial chicken farmer—a business he entered at the age of 18. In past years, during the peak of the farming season, he has been able to leave day-to-day operations of the poultry enterprise in the care of his friend and neighbor, Gene Edward Smith. While Shelby is happy with the stability that growing chickens has brought to his finances, many farmers in the area, including his father, have soured on the industry, claiming it puts farmers in too much debt and at too much risk for too little return.

“The other thing you have to know about farming is that there is no way you can do it yourself,” Shelby says. “I’m a lot more than just one old boy planting a pea patch. I’m literally surrounded by good help.”

He rattles off the names of family members, friends and two full-time farm hands, describing what they do for the business. “So if you want to farm, the first thing you have to do is get 10 to 12 dang good people to help you,” he says. “If any one of them decided to jump ship I don’t know what I would do.”

The back doors of the pickup pop open, and the team sets to work. Shelby puts the truck in gear and eases forward. Full-time farmhand Gustavo Florencio mans the bed while his brother-in-law, Regal, and a high school-age neighbor, Lynn, fan out to one side, staying parallel. Lynn stoops and rises, imitating a shot-putter as he arcs a watermelon 10 feet through the air. It is caught by Regal, and in the same movement floated to Gustavo and stacked in the pickup bed.

“I’ve got the easy job,” Shelby says sheepishly.

He describes the effort and expense of laying irrigation tape, a flat, hose-like apparatus that drips water, and the worry he had over his crops this year. While this part of East Texas skirted the brutal drought felt in much of the state, the period between rains was enough to leave many fields burned up when they should have been peaking.

“That last rain a week ago really saved us,” Shelby says. Despite some long, dry spells, it has been a record year for his watermelons. “We’re on our fifth cutting, and that’s just about unheard of,” he adds.

Since taking over operations from his father eight years ago, Shelby has added well systems and drip irrigation—a rarity for a region where crops almost exclusively are grown on dryland farms. The improvements helped him reduce his total farmed acreage almost by half—to 80 acres—and have saved a few seasons from ruin, including this one.

“We worked real hard. And I prayed about it. We’ve had a good crop,” Shelby says.

Back at the roadside farm stand, James—a cousin of Shelby’s wife, Renee—and James’ wife, Natalie, are handling a steady stream of customers. Recognizable by its weathered farmhouse and patches of merciful shade beneath tall pines, the stand has been a landmark for more than 28 years on U.S. Highway 96 south of town. This roadside stand and a trailer pulled to the town square at the beginning of the season are the only places you can buy Johnson produce.

“We used to farm commercially,” says Royce, who 15 years ago transitioned sales exclusively to the family’s farm stands on the highway and on the square. “You used to be able to sell to local grocery stores, but all that changed. Now they only buy from the big wholesale markets. We couldn’t compete in wholesale.”

“Now we can focus on quality instead of quantity,” adds Shelby. “Commercial growers might grow a certain variety of tomato just because it ships better. We grow for taste.”

At the roadside operation, boxes of green and fresh ripe tomatoes are stacked on tables and under a small, blue canopy tent in front of the house. Displays of cucumber, squash, okra, peppers, sweet corn, new potatoes and cantaloupes share space with a variety of relishes, sauces and jams made by Shelby’s mother, Louise. A glass-door chiller on the porch holds bags of shelled purple-hull peas—a local favorite—as well as butter beans. Hundreds of watermelons cover tables of steel mesh. Hundreds more are stacked on the ground.

But the showstopper is a cluster of eight watermelons as big as hogs, piled to one side near the front of the stand. This is Shelby’s store window dressing. Travelers spy them from the road and stop to take pictures of them or people with them as if the melons were celebrities. In fact, three of them are. They won third-, fourth- and fifth-place prizes at the 20th annual WHAT-A-Melon festival in Center the weekend before. The first-place winner isn’t here. It’s also from the Johnsons’ melon patch and holds court at the stand on the square.

“I could have sold those 50 times,” Shelby says, pointing at the monsters, “but they’ve made more money for me sitting right there.”

Saturday, July 18

We meet at dawn at the pea patch where Gustavo and his brother Miguel, the other full-time hand, are already picking purple hulls. Meanwhile, Louise is picking green tomatoes, and Royce is pulling sweet corn. After bagging and weighing peas and setting them aside to be shelled, Shelby will make stops to collect squash and okra, watermelons, shelled peas and ripe tomatoes picked the evening before. Everyone converges on Center town square around 8 a.m.

“Mama’s the one that built that business on the square,” Shelby says. “When she started that stand 20 years ago, she didn’t make much. And she would sit there all day.”

Today, the stand in town enjoys a steady stream of repeat business. Cars and trucks begin rolling in by 8:15 a.m. Some people get out, but many just lower a window. Shelby and Renee’s daughters, Olivia, 8, and Jenny, 14, offer enthusiastic drive-up service. Their cousin Cody, 14, is here from Conroe for the summer and is also helping at the stand. Sitting on a truck bed full of watermelons, he launches into an explanation of why small towns are better than cities: “You know everybody, people are nicer, there’s basically no crime …”

Jenny is on her cell phone calling the local radio station to make sure there’s an announcement about the “farmers market” at the square. In reality, the Johnsons are the farmers market. The only competition is a man selling eggs from his pickup.

Renee watches Olivia sweet-talk a lady with dark glasses. It seems everybody knows everyone else. These shoppers are more than customers, they are longtime friends. Olivia gives the lady a hug and helps her pick out some cantaloupes, then delivers them to her car. For this she earns a dollar tip, which she pops in the air to show her sister when the lady drives away.

“Try this,” James says.

We are back at the roadside stand on the porch where James has just cut the heart from a yellow-meat watermelon. Some friends have stopped by to pay a visit. He slices the meat, passing chunks all around. The yellow is almost iridescent, perfectly sweet with a texture grainier than a red meat.

Shelby, a cell phone on one ear, cuts open a red watermelon, skewers a square from the heart and slides it off with his teeth. He is tacking down plans for when everybody will meet up for lunch.

An hour later, 30 or more people of all ages have gathered at a small house in the woods for a feast of fried fish and a little bit of everything the Johnsons grow on their farm. Known simply as “The Cabin,” this one-room structure that’s flanked by sheds and kennels for hunting dogs is a hunting camp and the stage for occasional spontaneous lunches like this one. All of the Johnsons and many of their friends from the community are here. It has been weeks since the last lunch, and enthusiasm is high.

Food is piled up along a serving table and on top of an old, white enamel-plated stove.

Two deer heads watch from adjacent walls. Antlers and a few hornet nests hang from the rafters. Men and women grab plates and file through the food line, then huddle at tables to play Texas 42. After most are settled and fed, a storm blows in. Olivia and four other girls lie on a bed in the corner, propped on their elbows, and peer through the window to watch rain pour off the tin roof. It feels like a gathering of extended family.

“I’m blessed,” says Shelby. It’s now September. The harvest ran unusually long due to late-season rains. Shelby has had a good year and now is out for some R&R at another family hunting cabin.

“I’m sitting here on the Sabine River, and I hope to be here another month,” he says. This off time—to hunt and fish and just relax—is part of what Shelby loves most about farming. “My priorities might be a little different than others,” he explains. “My truck is probably worth $2,000, and my wife doesn’t have any credit cards. I don’t make a lot of money, but I sure do enjoy my life.”

———————————-

Jody Horton is an Austin-based writer and photographer whose stories and photographs have appeared in previous issues of Texas Co-op Power.