In the darkness of a cold winter night, we follow our guide and the beam of his flashlight through a short stretch of rocky, weedy, West Texas prairie to the spot where his treasure lies buried.

Abilene city lights twinkle in the distance, and the silence of this open terrain is broken only by howling coyotes and our soft chatter and pitter-patter.

We stop at the edge of a 54-foot-diameter disk of cement.

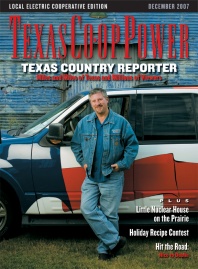

Our guide, Larry Sanders of Abilene, explains that it is the cap covering his 185-foot-deep nuclear missile silo—an $18 million relic of the Cold War he is acquiring for $54,000 through a lease-to-own economic development agreement with the city of Lawn.

He is turning it into a historical preservation center at the cost of up to another $200,000. And he plans to continue collecting revenue from visitors who already rent the facility for business meetings and catered dinners. He believes the center will become the first of its kind in the country and the first 20th century addition to the 19th century Texas Forts Trail.

The Cold War is raw enough in our collective memory that few Americans see its trappings as historic sites worthy of tourist visits. But it’s possible to imagine people 50 and 100 years from now being drawn to the site as they are to the state’s eight historic frontier forts.

That the Atlas ICBM was never launched against an enemy does not make Texas’ role in the Cold War less significant, Sanders says. To have fired an Atlas at an enemy at any time during its deterrent life “would have spelled the ultimate failure of the system,” he says.

Many historians agree that American and Soviet fears of mutually assured destruction from nuclear weapons, including the Atlas, kept the superpowers from direct warfare for more than 40 years.

Sanders’ silo in Lawn was one of 13 Atlas ICBM F-series silos built in Texas—12 of them near Dyess Air Force Base (in Abilene, Albany, Anson, Bradshaw, Clyde, Corinth, Denton Valley, Lawn, Nolan, Oplin, Shep and Winters) and one north of Vernon along the Texas-Oklahoma border. Other F-series silos were based at Schilling AFB, Kansas; Lincoln AFB, Nebraska; Altus AFB, Oklahoma; Walker AFB, New Mexico; and Plattsburg AFB, New York.

The F-series was America’s first missile to assure survival of a first-strike nuclear attack through retaliating second-strike capacity. During the Cuban Missile Crisis at the height of the Cold War, the silo housed a missile 85 feet tall and 10 feet wide. “It would have reached Russia in about 30 minutes,” Sanders says.

At the center of the cap are two flat concrete-and-steel doors, each 45 tons and more than 2 feet thick. At the press of a button, those doors would have opened in seconds, allowing the missile to roar into the sky.

We proceed to view the rest of Sanders’ treasure as he leads us about 25 yards away to his underworld abyss’s grand entrance—a concrete structure resembling a little outhouse on the prairie. It stands about 10 feet tall between a power pole and a willow tree.

The smell of fresh paint greets us as we proceed through the entry portal’s hinged door and descend two stories down a well-lit stairwell into the launch control center.

The silo was only in use from 1962 to 1965, when newer technology prompted the U.S. Air Force to terminate the Atlas ICBM mission. The military sold the Lawn silo in the late 1960s to the nearby town, which bought it for use as a public shelter.

By the time Sanders took possession of the silo in 1999, it was in such disrepair that murky water with dead critters had risen to the fourth stair, making the place reek like a fish market.

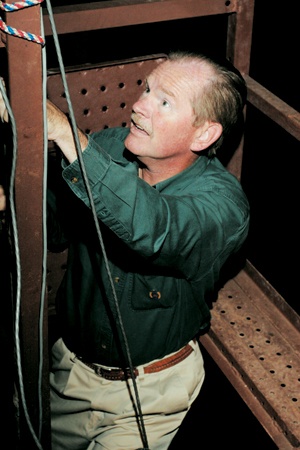

We continue trailing Sanders through a steel entrapment door and two blast-proof doors, then down a hallway lined by Christmas lights. They’re connected by an extension cord to an electric panel powered by Taylor Electric Cooperative. Though the facility has not yet been rigged with permanent fixtures for electricity, the power source is a vast improvement since Sanders’ initial days there working with flashlights, camp lanterns and a portable gasoline-powered generator.

“Believe me, almost anything is better, and probably much safer, than underground life with a kerosene lantern,” he says.

He plans to add electrical wiring, heating and running water within the next year.

During the tour, he talks with excitement about his plans to turn the place into a museum-type center filled with Cold War relics.

“What safer place for the artifacts?” he asks with a smile.

Sanders’ grassroots effort to restore the facility has been fueled almost entirely by his own money and sweat. While some men tinker with lawn mowers, Sanders passes Saturday afternoons working on his missile silo. Shortly before our visit, he had been painting the walls of the stairwell and hallways. It’s the latest of his labors of love, which began in 1999 when he, his family and friends removed knee-deep water, organic material and trash from the launch control center entry stairwell using pumps and water hoses.

We descend another stairwell to the launch control center, then down one more flight to a short tunnel connecting the control center to the silo—the now hollow colossal former home of the missile.

We step onto a railed stairwell platform and into the darkness, where our voices and the sound of dripping water echo. Sanders points his flashlight to the opposite wall 52 feet away, then up toward the ceiling 45 feet above our heads.

He then points down below us where the stairwell descends 50 feet to a yellow raft floating on the surface of water 90 feet deep.

“This site will vastly outlive the pyramids,” Sanders says. “Thousands of years from now, scientists will look at this and say, ‘What was that about?’ ”

During its disuse, the abandoned silo became a popular hangout for area high school and college kids, who would sneak into it for weekend adventures and leave their marks with graffiti on the walls, Sanders says.

Sanders, a graduate of Abilene Christian University, was among those who used to explore the nearby Oplin silo, so he understands how kids managed to get in. But he has yet to figure out how one particular marking made it onto a spot high on the wall inside his missile chamber.

He points his flashlight up toward the ceiling to the barren wall, where 75 feet above the water, “BUD” is painted in red letters. The sight of it with nothing nearby to climb on is chilling.

I ask how Bud got up there.

“I don’t know and don’t know if he ever made it down safely,” Sanders says, pointing back toward the water.

The possibility of human remains lurking in the pool below is one reason Sanders won’t scuba dive there just yet, even though he has done so in other missile silos. (Dive Valhalla, another missile site some 20 miles southwest of Abilene, is used by experienced divers.)

On that note, I head for the exit.

——————–

Read more about the Lawn Atlas Missile Base at www.atlasmissilebase.com.