The roar of falling water grows louder as our canoe glides to the edge of the drop.

Our eyes are fixed on a narrow channel. Clear, deep and a few feet wide—just wide enough—it cuts between two small stacks of whitewater. We point the bow to the middle of it, dig in hard with our paddles and gain speed as we near the lip.

“Perfect,” shouts my friend Stefan from the bow.

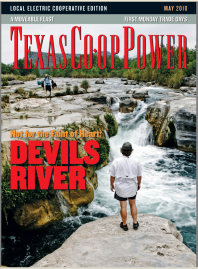

Just four hours into the trip, we have settled into a familiar rhythm. Much of what we have seen of the Devils River so far, since our put-in at Baker’s Crossing north of Comstock, is more creek than river. Often shallow and rocky, the narrow passages are technical, requiring constant adjustments to avoid obstacles and stay in navigable water.

From his seat at the bow, Stefan can see whatever lies in front of us one to two seconds before I can. This makes him the navigator. Since you can only rudder from the stern, his split-second decisions are relayed to me: “Left! Right! Hard right! Straight! Speed-Speed-Speed!” We have been a good team so far—we haven’t swamped the boat yet. A number of runs have been graceful enough for us to call them pretty, and a few paddle high fives have been exchanged.

These small successes have now given us the confidence to aim for the drop, not knowing into what—at least not exactly—we would be dropping. Now, as the boat slips over the edge, the world slows, the volume is turned down, and a few things happen at once: Stefan shouts the word “RIGHT!” several times urgently—I see the large rock we are falling toward, observe how the river hits it and curls back at an almost 90-degree angle to the right—my gut tells me to go left.

Splash! The world is at full speed and volume now as I dig a quick, desperate right stroke to shift us left. We smash into the rock, but at a slight angle. It’s enough, and the boat is bounced left. Still upright, we fall and scrape and bounce over a series of lesser rocks, miraculously sliding into a pool of calm water at the bottom. Not pretty, but we made it.

Being men, whatever impulse we have to warn our friends behind us is overpowered by curiosity. We turn back upstream to watch. Jeff and Brendan are looking tentative as they edge over the drop. For a moment, it seems this slow approach might actually allow them to make the sharp right before the boulder, but in the next they are both in the water and the canoe has been pinned sideways against the rock. We paddle upstream frantically and jump into the rapids. The water is only three or four feet deep here, but pushing hard. Brendan is screaming and pulling in vain at the stern to free the boat.

“It’s going to wrap! It’s going to wrap!”

The hull is already flexing and crumpling against the force of water that will soon and inevitably bend it into a U around the center point on the rock where it is pinned. The boat has been wrapped and patched before and won’t survive this long.

We have only seconds before the sides will be crushed and ripped open. A few panicked, adrenaline-fueled moments later we are all in the rapids with a handle on the boat.

“One, two, three!” We heave and strain against the relentless crush of water, but the boat barely moves.

“One, two, three!” again, and harder this time, but nothing, nothing—then suddenly the boat pops free, springing back to its original shape as it skids over the top of the rock.

In the next several minutes the boat has been emptied, inspected, and repacked. We are all a little shaken by the close call. The panic and the plunge into cold water have had a sobering effect.

We take the next six hours to our first camp at Devils River State Natural Area about 16 miles downriver a little more cautiously, contemplating the situation we would have been in if this—or anything else—had gone wrong. You are often many miles and hours from any help on this isolated and pristine stretch of the Devils. Our dinner of steak and a few smallmouth bass caught along the way feels much deserved.

We face two long and strenuous days ahead and will cover nearly 50 miles in all before the takeout at Rough Canyon Marina on Lake Amistad where we left a second car to run shuttle. It’s an ambitious plan to cover so much ground by canoe in so little time. We wish we could stay longer to fish the riffles and eddies, to admire the high rugged cliffs, and snorkel the deep emerald pools. We promise ourselves, and each other, to return.

Jody Horton is a freelance writer and photographer and a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power.