Doug Baum strides through the prickly Chihuahuan Desert of West Texas, a straw cowboy hat shading his face from the sun and a string of five camels sauntering behind him.

I’m perched high atop one of those camels, listening intently as Baum, owner of Texas Camel Corps, points out a canyon wren’s nest, stops to inspect a rust-colored millipede marching across our path and then explains the role camels played in the Lone Star State’s history.

“Texas is perfect for camels,” says Baum, born in the West Texas town of Big Spring. “That point was not lost on the Army when they decided to use camels out here in the 1850s.”

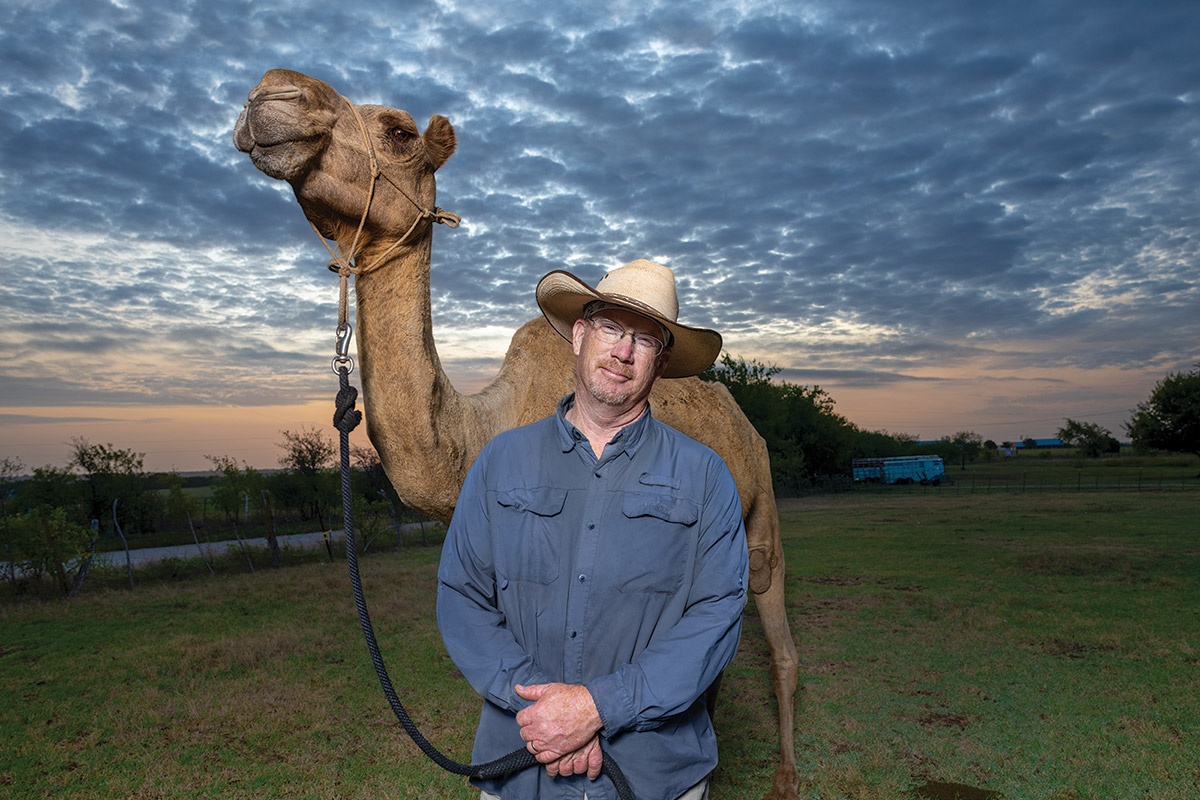

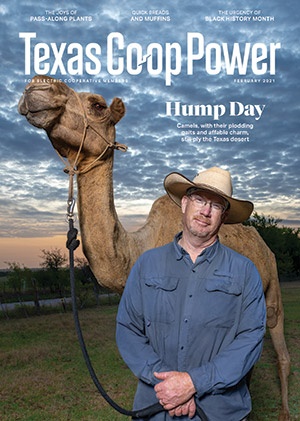

A face that only a … no, that anybody could love.

Scott Van Osdol

That’s when the U.S. military imported 75 camels from Egypt, Turkey and Tunisia for use as pack animals. For nearly a decade, the heat-resistant creatures carried water and hauled supplies for the U.S. cavalry at Camp Verde, south of Kerrville.

When the program ended in 1866, the army sold the animals. Some wound up in California; others hauled freight between Texas and Mexico; a few ended up in traveling shows; and some made their way to Austin, where they were kept along Congress Avenue near the river and then sold off a few at a time.

Today Baum, who lives with his menagerie on a farm near Valley Mills, where he is a member of Heart of Texas Electric Cooperative, keeps the camels’ history alive by introducing his cartoonish but affectionate creatures at events around the state. I’ve joined him at Cibolo Creek Ranch, south of Marfa, for an overnight camel-riding trek to learn more about the role they once played in the Big Bend.

Texas Camel Corps owner Doug Baum throws a saddle on Richard at his farm near Valley Mills.

Scott Van Osdol

I feel like I’m riding a rocking chair strapped to a stepladder that’s being dragged down a gravel road. It’s both rough and rolling, with the bonus that my camel, Cinco, swings his neck around to give me a big goofy smile now and then.

Baum first fell in love with camels while working as a professional musician in Nashville in the 1990s, when he played drums for country music star Trace Adkins. He took a day job working at the Nashville Zoo.

“I had zero experience with camels,” he says. “Within a week I was absolutely smitten. They’re sweet, affectionate, playful and so, so gentle.”

Author Pam LeBlanc perched atop Richard.

Scott Van Osdol

They’ve also got leathery, pie-sized feet; spindly, stiltlike legs; nostrils that squeeze shut to keep out blowing sand; and peach-sized eyes fringed in lush, 3-inch lashes.

Baum stuck with music for a while, but eventually “the camel thing just won,” he says. “It was an obvious choice to me.”

He moved back to Texas and in 1998 bought four camels, with the idea of using them for educational programs. Two of those camels—Richard and Cinco—are with us on this cool September afternoon, slowing periodically to munch on creosote bushes.

“They teach me what I should be—patient, observant, methodical,” Baum says of his camels. “These are things I recognize I lack in myself.”

He leads treks each spring and fall at Cibolo Creek and delivers members of his eight-camel herd to museums, parks, schools and libraries. He also leads treks in Egypt, where he has a second home, and if you need a camel for a church Nativity, he’s the guy to call.

Part of Baum’s mission is to dispel myths about camels. They’re not, he says, ornery, smelly beasts that spit at people. Their humps aren’t filled with water, either, though a camel can go 10 days or more without a drink. Camel humps—one for dromedaries, two for Bactrians—are filled with fat. (If you’re riding a single-humper, you’ll sit on a padded seat behind the hump. For a two-humper, you ride between the bumps.) Camels can be downright cuddly, and they don’t spit—although llamas, which are closely related, do.

I learn, when Cinco exhales on me, that the stinky part of the stereotype rings true. Camels’ awful breath is both sweet and pungent, like grass clippings mixed with syrup—in part because they chew their cud. They are ruminants and employ three stomachs to process their food. Stand next to one for a few minutes, and you’ll hear that digestive system in action, gurgling and glugging like a clogged drain. Also, they fart—loudly and potently.

Doug Baum, walking behind the first camel, leads a trek through the desert at Cibolo Creek Ranch, south of Marfa.

Pam Leblanc

Two other guests on the trek, Sue and Randy Howerter, Guadalupe Valley EC members, are equally taken by the animals. Randy, who makes musical instruments, met Baum at a festival in New Braunfels. Sue, a blacksmith, was intrigued, too, and the Seguin couple visited Baum’s farm, where he lives with his family, the camels, five miniature donkeys, a pair of dogs, a flock of chickens, assorted sheep and goats, one horse, and “too many” kittens.

After that the Howerters needed no convincing. They headed to Cibolo Creek Ranch, where we all loaded sleeping bags and pajamas into large canvas saddlebags; climbed aboard our kneeling, straw-colored steeds; and hung on as the animals rose to full height.

“Sometimes you get an attachment to animals,” Sue Howerter says. “It’s the same with camels. They have so much personality and character.”

Before our two-day trip ends, we’ve lumbered a dozen miles across a stark landscape that looks like the backdrop of a John Wayne movie, soaked in a spring-fed creek, eaten a traditional Moroccan meal, sung around the campfire, watched shooting stars streak across the sky and listened to coyotes yip as we snuggled in our tents.

But it’s the camels that get top billing. And that’s just how Baum likes it.

Pam LeBlanc, an Austin-based adventure journalist and former staff writer at the Austin American-Statesman, prefers riding a camel to driving a car in heavy traffic. Her book, My Stories, All True: J. David Bamberger on Life as an Entrepreneur and Conservationist, was published in September.