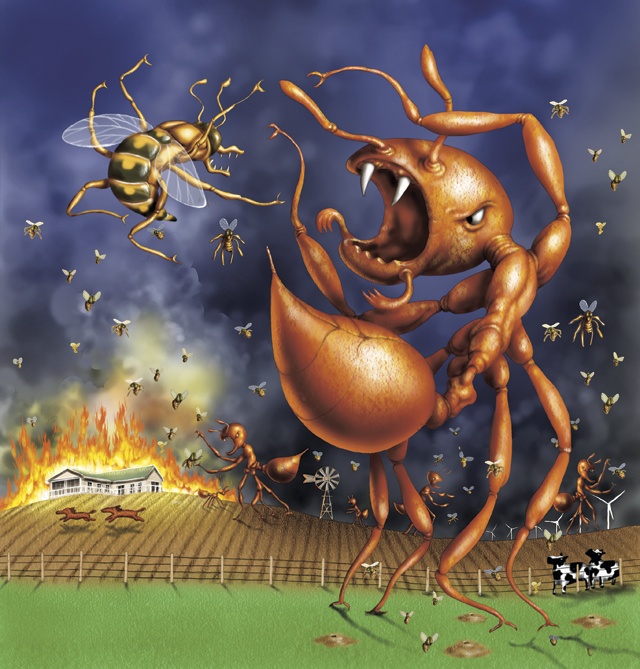

Under attack. Nowhere to run. Nowhere to hide. The fire ants cower. They panic. The flies keep coming. Dive-bombing. Injecting eggs. No mercy. It’s a fight to the death.

And the flies always win.

——————–

Texans burn, drown, smash, poison and cuss red imported fire ants. But 20 years of research at The University of Texas reveals that one of the most effective weapons in our arsenal against these relentless invaders just might be—drum roll, please—tiny phorid flies.

The gray-brown, gnat-like insects from South America star in a scene straight from a B-grade horror movie. A female fly sneaks up behind an unsuspecting worker ant and lays an egg in its body. The egg hatches, and the larva moves into the ant’s head, sending the host ant out of the colony—zombie-like—to find a place to die. The ant’s head eventually falls off, providing a nice, hard shell in which the larva pupates into an adult fly. The whole process takes about 45 days.

It’s too soon to say just how much damage the flies are actually inflicting, but scientists know this: The presence of phorid flies around mounds drives ants crazy and disrupts their normal behavior.

So does this mean we’ll never again have to spend hard-earned dollars on ant bait, or precious time pouring boiling water over swarming mounds? (The latter method, by the way, is reasonably successful—see our Weapons in the War on Ants sidebar about what works and what doesn’t in trying to kill these fierce invaders.) No. But for Texans waging war against red imported fire ants, it feels as if the cavalry—in the form of tiny winged crusaders—has arrived.

Texans hate invasive fire ants, and with good reason. Armed with back-end stingers and serrated mandibles, or jaws, they aggressively attack and can injure or kill livestock and wildlife, particularly when animals step into or lie down on mounds. They can produce life-threatening allergic reactions in people. The ants render lawns, parks and other outdoor areas inhospitable. They displace native ants, reduce native insect populations and interfere with pollination. A bane of agricultural producers, the ants build mounds that can damage mowing, shredding and baling equipment.

These invaders aren’t satisfied with spoiling the outdoors, either: During the winter, fire ants seek out the warmth of electrical circuit boxes, causing shorts responsible for fires (although fire ants are named for their burning sting, not their ability to ignite flames).

Red imported fire ants, in fact, according to Texas A&M University researchers, cost Texans roughly $1.2 billion a year—a total that includes the damage these critters cause and the cost of our efforts to fight them.

Stowaway Fire Ants

Fire ants haven’t always been such a problem. Texas is home to a native species of fire ant (Solenopsis geminata), but natural enemies and competition have kept its numbers at a tolerable level. The natives seldom bother most people.

Red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta), however, are native to South America. They arrived in the U.S. around 1930 as stowaways on a ship from northern Argentina that docked at Mobile, Alabama. The ants quickly spread throughout the southeastern U.S. Crossing into East Texas in the late 1950s, the ants rolled unimpeded to the western edge of the Hill Country, where cold and dryness slowed their progress.

With no natural enemies here, the invaders quickly outnumbered native ants. No one knows just how much greater their numbers are, says Rob Plowes, a research associate at The University of Texas’ (UT) Brackenridge Field Laboratory in Austin. But 200,000 to 250,000 imported red fire ants live in a typical colony, and many a landowner reports mounds covering pastures like a deadly pox. The ants’ numbers vary with rainfall and temperature, with more found in warm, moist areas or where soil has been disturbed. Their highest densities occur in the eastern and southern portions of Texas.

Fortunately for us, and unfortunately for them, fire ants showed up at the Brackenridge lab, 82 wooded acres on the shores of Lady Bird Lake, in the early 1980s. Watching them bulldoze across the property inspired Larry Gilbert, professor of integrative biology and lab director, to create The University of Texas Fire Ant Research Project, with the goal of finding a self-sustaining, biological control method.

In contrast to chemicals—which kill pretty much everything in their path, cost a lot and must constantly be re-applied—biological control, or biocontrol, mostly targets the invasive species and is something that will keep going on its own, Plowes explains.

But biocontrol is complicated to figure out and establish. First, using their genes, researchers matched invasive ants to the specific locations from which they originated in South America. Then, the scientists explored those home ranges for potential ant predators and parasites. This somewhat tedious work revealed that the natural enemies keeping fire ants in check in their native habitats include wasps, nematode worms, pathogens such as bacteria, fungi and viruses—and flies belonging to the Phoridae family (genus Pseudacteon).

Attack of the Killer Flies

UT researchers worked with South American biologists to identify 24 phorids, Plowes says. Each is very host-specific and primarily attacks the invicta ant species, the type menacing Texas. (The flies will attack native fire ants, but don’t make them hosts.)

UT began experimental releases of phorids in Austin in 1995, initially setting flies loose near mounds in hopes that they would attack the ants. Later, the lab began using what Plowes calls a Trojan horse approach, using infected fire ants to unwittingly carry the enemy back to their homes.

To do this, researchers bring a bucket full of ant colony members into the field lab, fill it with water to float ants to the top, and transfer the scrambling insects to a tray. In the Mass Attack Chamber—a room entered space station-style via an air lock—trays are placed in boxes containing flies. The flies lay their eggs, and the infected ants are returned to their original colony.

UT’s phorid fly research was great news for landowner Wesley Horn-

buckle. By the early 1990s, invasive fire ants had infested his family’s 1,875-acre ranch on the Trinity River near Centerville, building mounds roughly every 15 feet in open areas. Hornbuckle observed a marked decline in the number of quail and blames the ants for failed efforts to re-establish wild turkeys on the land. For four years, he fought back with expensive chemicals—$2,000 per application—but the ants always came back.

So in 2009, Hornbuckle, his brothers Brad and Will and friend Kevin Johnson made nine trips between the ranch and the Austin-based lab, bringing buckets of ant beds and returning the infected residents to their original mound sites. Within a year, phorid flies were well established on the ranch.

“Over time, Rob says we should see the ants decline about 15 percent a year,” Hornbuckle says, explaining that with the flies present, the mounds aren’t expected to be as big or as numerous.

Chemical treatment, Hornbuckle says, temporarily depleted the ants’ numbers, and after applications, he would see a huge increase in cottontail numbers.

But the flies offer the promise of a long-term solution in the fight against red imported fire ants. “I just hate those suckers,” Hornbuckle says. “It is personally rewarding to see them go.”

Mounds of Trouble for Fire Ants

Researchers can’t yet quantify how many fire ants the flies are killing. But projections show that in areas where flies are introduced, they infect up to 1 percent of worker ants. “That’s a huge amount of fire ants going down the drain,” Plowes says.

But what’s more important, Plowes says, is that the mere presence of phorid flies makes life harder for the ants. The ants clearly don’t appreciate being hijacked as larval hosts and frantically try to escape dive-bombing phorids by going underground or hiding in the nest. This restricts the ant colony’s ability to gather food, effectively limiting the size of a colony and its ability to found new ones (ant colonies spread much like beehives; when things get crowded, a queen and workers leave to start a new mound). So, with phorids around, fire ant mounds aren’t as big or as numerous, putting the invaders more on the par with native ants.

In more good news for Texans, Plowes says that phorid flies introduced on public and private land by UT, Texas A&M, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and various state agencies have spread to about 160 million acres, more than half the fire ant range in Texas (see map at www.sbs.utexas.edu/fireant).

Prevailing winds apparently have aided their spread. “The flies normally move maybe tens or hundreds of meters a year,” Plowes says, explaining that the leading edge of the population moves about 40 or 50 miles per year, representing 10 to 12 miles per generation. Small insects, including phorids, can get wafted 5,000 or 6,000 feet up in the atmosphere and picked up by winds aloft, then rain down somewhere else.

Naturally, Plowes has been asked whether Texas will be plagued by swarms of the flies. Not likely, he responds. As already noted, the South American phorids have a significant preference for a specific host ant, and the lab’s years of research prove that bringing them here hasn’t changed that. The flies don’t attack any old fire ant, and without the proper ant host around, the flies die off.

Plowes stresses that despite the promising results of phorid fly attacks, we’ll never eliminate invasive fire ants, in Texas or anywhere else. But long-term, he believes we can reduce them to more tolerable levels through some combination of flies, pathogens, native ant recovery and environmental stress. However, it will, he cautions, take time—perhaps decades.

Meanwhile, landowners plagued by invasive fire ants can take comfort in the knowledge that at least help is on its way. So for now, keep on burning, smashing, drowning or poisoning them. And practicing patience.

——————–

Melissa Gaskill, a freelance writer based in Austin, is a frequent contributor to the magazine.