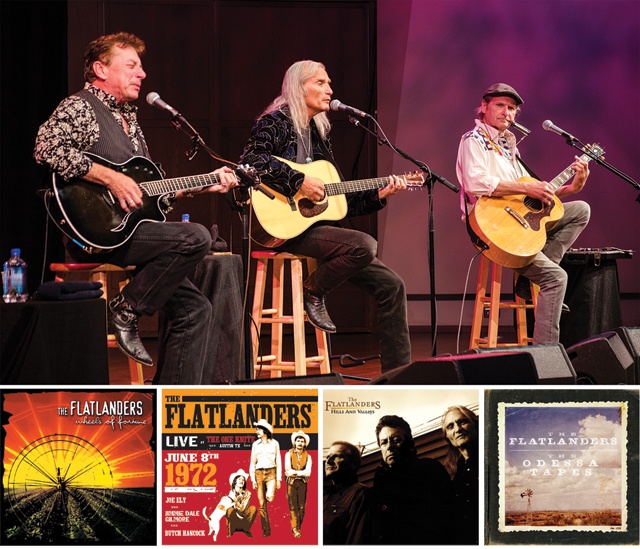

This is an excerpt from John T. Davis’ new book, “The Flatlanders: Now It’s Now Again.”

Genesis

Joe used to say that none of us had a thimbleful of ambition. But between the three of us, we had a towering lack of ambition. —Jimmie Dale Gilmore

The thing that is startling to realize is that, for all the gravitas the Flatlanders and their music acquired over the years, their tenure as an actual, functioning, gig-playing band was startlingly brief. From the time they coalesced around the living room of the 14th Street house until they went their separate ways in the wake of their Nashville recording session was only a year, maybe less.

The fact that they even got together is a study in serendipity. In the spring of 1971, Joe Ely had been knocking around in Europe; Jimmie Dale Gilmore had made a foray to Austin with his band, the Hub City Movers; and Butch had been studying architecture and photography in San Francisco. They just happened to all show up back in Lubbock more or less simultaneously.

“I was in touch with both of them,” Jimmie told No Depression magazine. “And at one point I said to Joe, ‘You know, I’ve got this friend who writes some really good songs. You gotta hear him.’ So we got together and we stayed up all night playing together and laughing. And that was the beginning of the Flatlanders.”

The core of the group was, of course, Butch, Jimmie, and Joe, along with Tony Pearson and Steve Wesson and, to a much lesser extent, Sylvester Rice. Others drifted in and out of the loosely knit group for short periods, maybe just a handful of times. There was guitarist John X. Reed and the reclusive songwriter Al Strehli, from whom Jimmie plucked some lovely songs, including “I Know You” and “Keeper of the Mountain.” There was also a drummer named Tom Jones, an artist named Jim Eppler, and accordionist Ponty Bone, who would go on to join the Joe Ely Band. It was Bone who would describe the Flatlanders’ tiny but select group of followers with a wonderful phrase: “small circles of good taste.”

Syl Rice, Country Lou D, and Royce Clark might have been eyeing the group in terms of record deals and radio play, but there wasn’t much thought given among the principals to building commercial momentum, or any sort of a music career in the sense that the public tends to think of it.

“We weren’t perceiving it through the eyes of someone trying to get into the music business,” said Jimmie, laughing at the very thought.

“The band was never created as a commercial entity, even though Joe and I were already set on professional [music] careers,” he continued. “That band came out of a circle of friends that had some musicians in it that liked playing together. We were beatniks!”

Speaking in 2013, he said, “In some people’s eyes, it’s sort of miraculous, the whole deal that we’re not only a functioning unit, but that we’re still friends. But it’s pretty natural, because the whole band worked that way from the beginning. The Flatlanders came about because we liked each other so much to begin with. Going off to Nashville and making the record was just a tangent.”

One struggles, in looking at their story then and talking to them now, to find any hint of discord or rancor or ego-driven one-upmanship among the trio.

Journalist Richard Skanse gave it a good shot, though, in a cover story for Texas Music magazine in 2000:

… 30 years of friendship and not a bump in the road? It’s just too good. Out with the skeletons.

“Well,” offers Hancock, “there was that nasty credit card scandal of Jimmie’s … ”

“Oh, and that Eskimo girl,” Ely adds cryptically.

“And Joe stealing a steamroller—when I got blamed for that,” continues Hancock, “there was some friction there.”

“We were in prison for a couple of years in Costa Rica,” offers Ely. “We were in the same cell, but we didn’t talk to each other for weeks.”

“That,” says Gilmore, “was Butch’s fault.”

The camaraderie ran deeper than just intersecting musical tastes or similar temperaments or happy geographical proximity. They are bound by a shared search, a yearning to, as the Hindu teacher Ram Dass and a latter-day Flatlanders song say, be here now.

“The three of us have always had a desire to understand everything we can understand,” said Joe Ely to the Statesman. “And to be very awake and conscious of everything that’s going on. That’s really all you can do in this universe. You can’t be certain of anything. But you can be present.”

That deliberate choice—to be awake and conscious and all on the same wavelength—gave the guys a level of creative intimacy that was almost subatomic. Joe might wake up and jot down a song that he had dreamed the night before … but in his dream, Butch had written the song and Jimmie was singing it. It came out in their performances, too.

“Their voices sound great individually, but they also blend,” said Lloyd Maines, who has played with and/or produced all three men individually and together. “They sound so different when they’re singing by themselves, but when they do harmonies it’s almost like they’re brothers.”

The Flatlanders played informally pretty much every night—hundreds of shows for friends, Ely recalled. But their paying gigs were sporadic and their crowds sparse.

“There’d never be more than ten people whenever we’d play somewhere,” said Ely, exaggerating for effect. “But we’d meet other musicians.”

Memories can be hazy things, and the Flatlanders shows that folks can recall seem almost maddeningly random in retrospect. They played at Tony’s and Laura’s Supernatural Health Food Store, a place called the Attic in the basement of an ice cream shop, and such coffeehouses as Tech’s microscopic bohemian population could support, including a place called Aunt Maudie’s Fun House. Debby Savage (aka “Little Deb”) said they performed at “maybe the Elks Lodge.” Tommy Hancock recalled them playing at the Unitarian Church and one time, he thinks, a state school for, as he put it, “retarded children.” One picture in the booklet included with “The Odessa Tapes” CD shows them playing on the commons at Texas Tech.

Their favorite venue, according to Hancock, was a place called the Town Pump.

“It was in a little old strip mall on 4th St.,” he said to No Depression magazine. “It was sort of a seedy place—gambling, and they say a prostitution ring ran out of there. But it turns out the only trouble we ever ran across down there was from the tenants next door. It was one of those success groups—motivational training, you know. One of them stabbed somebody in the alley one time. I guess they got motivated.”

“Syl Rice told me, ‘You’ve got to come hear these guys, they’re real unusual, totally off the cuff,’ ” said Maines. “So, Syl took me to the Town Pump [to see them]. I knew there was something there, but it sort of took me aback. They appeared a little disorganized, and the songs didn’t really have arrangements. At the time, I was used to playing in a rehearsed, arranged situation, but I thought it was great.”

But what the Flatlanders lacked in big-time shows and professional polish, they more than made up in repertoire.

Ely’s background, and natural inclination, were rock ’n’ roll. Gilmore was grounded in classic country and Western Swing, and Hancock came out of the wordy, Dylan-esque folk music universe. When they came together, each brought something to the table that the other two had largely not experienced.

“Between us, we had hundreds of songs that we knew, and we’d sit up all night and play them,” said Ely, speaking at his home in 2012. “It was a vast repertoire of songs. The musicians in Lubbock were from all different worlds. There were the rock guys and the folk guys and I kind of went in between them. I went to Europe for a year, then came back and got with the Flatlanders and I had a whole other repertoire than Jimmie or Butch, and I found their repertoires fascinating.”

He searched around on his computer and came up with a scanned image of a couple of Flatlanders set lists to illustrate his point:

Here’s Daddy Dave Dudley’s truck-driving anthem, “Six Days on the Road,” and Hank’s “Honky-Tonkin’ ” and Willie Nelson’s “Bloody Mary Morning.” Over yonder is the Cajun waltz “Jole Blon,” an untitled schottische, Dylan’s “One Too Many Mornings,” and Flatt and Scruggs’s “Salty Dog Blues” and Buddy’s “Peggy Sue.” Mix that stuff up with the Lloyd Price/Elvis hit “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Black Snake Moan,” and Townes Van Zandt’s “Waitin’ Around to Die.”

Throw in some originals (mostly by Butch), and you have a pretty good idea of the Flatlanders’ home range. “Vast,” as Ely says.

With Jimmie singing most of the lead vocals (though not all; their demo and Nashville album tracks give a false impression), Ely’s rudimentary learn-while-you-earn Dobro playing, Steve Wesson’s ethereal, oscillating musical saw, and Tony Pearson’s jaunty mandolin licks, they sounded like nothing going on in the commercial country or pop music worlds in 1971. If they are to be placed in context at all, it would be more fitting to rank them with contemporary Americana groups like the Lumineers or The Civil Wars.

I never thought that I would ever wonder why

I ever said goodbye

I had my hopes up high

—“Hopes Up High” by Joe Ely

——————–

Text by John T. Davis excerpted from “The Flatlanders: Now It’s Now Again,” used by permission of the University of Texas Press. Copyright © 2014.