A trip to the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum in College Station brings an expectation of seeing a line in the sand, given that the 41st U.S. president told the world he was drawing one right before delivering a one-two punch of shock and awe against Saddam Hussein in the first Gulf War.

And, lo and behold, there it was on the second floor of the administrative office of the museum, save two small details—no sand, no Saddam.

On one side, this side, was a long hallway lined with paintings of presidents leading to a large oil work of the presidents Bush, père and fils, standing side by side.

On the other side, that side, was what Supervisory Archivist Bob Holzweiss had promised minutes earlier.

“Here,” he says one Sunday last fall, as he unlocked a set of double doors, “is the Indiana Jones room.”

The doors opened to reveal a real-life warehouse of antiquities, extending as far as the eye could see, even if that was mostly because the lights were off at the far end. There was no Ark of the Covenant, just row after row of neatly labeled and indexed boxes containing 45 million documents.

And that line? Only museum personnel are allowed to cross it. Crossing it is not part of the ticket-buying tourist experience, or even that of the sharp-eyed researcher keen on mining the documents for nuggets of history. Academics and historians can access the documents only in secure viewing rooms. But peeking into the storeroom was an eye-opening glimpse into one important aspect of U.S. presidents and the keepers of their legacies: They’re government-sanctioned and -subsidized political packrats.

“They saved everything,” Holzweiss says of President George H.W. Bush and wife Barbara, “and they gave it all to us.”

Presidential libraries are the executive branch storage unit for everything from documents to photos to bicycles to gifts of ruby-encrusted gold stirrups from the king of Morocco—pretty much anything that might be of value, whether it’s historical, cultural or just plain curious. George W. Bush received 43,000 gifts from U.S. citizens and foreign heads of state, but before you suggest an Oval Office garage sale to erase the national debt, realize there are strict laws that govern what to do with those gifts. (See Article I, Section 9, U.S. Constitution.)

So White House staff painstakingly packs and sends them to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, or NARA, for that day when a president’s veto power is no longer over Congress but over how their own legacy is seen in the world of postpresidential revisionism.

On a sun-splashed day on the Southern Methodist University campus last April, all five living presidents convened for the opening of the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum. Amid the pomp and pageantry, President Bill Clinton stepped to the presidential seal-embossed lectern and candidly said with a grin: “I told President Obama that this is the latest, grandest example of the eternal struggle of former presidents to rewrite history.”

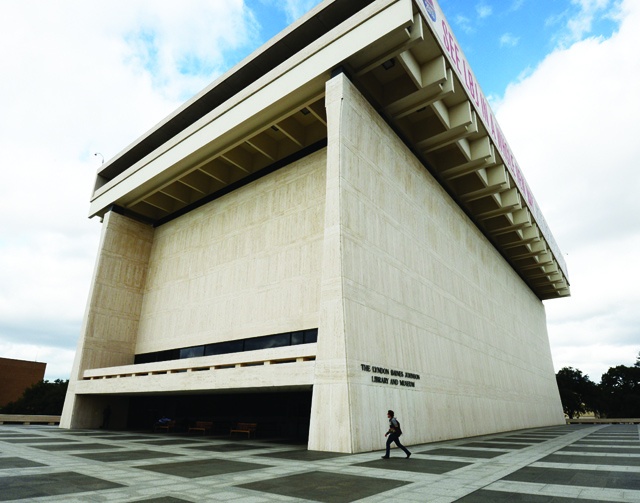

Much of that history is being reshaped right here in Texas, which leads the U.S. with three presidential libraries—the LBJ Presidential Library on the University of Texas campus in Austin; the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum on the Texas A&M University campus in College Station; and the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum at SMU in Highland Park.

“These shrines are amazing, and they can be a little weird,” says Benjamin Hufbauer, a University of Louisville professor and author of “Presidential Temples” (University Press of Kansas, 2006). “There’s nothing modest about them. They are all pretty aggrandizing. Each one tries to top the last one.”

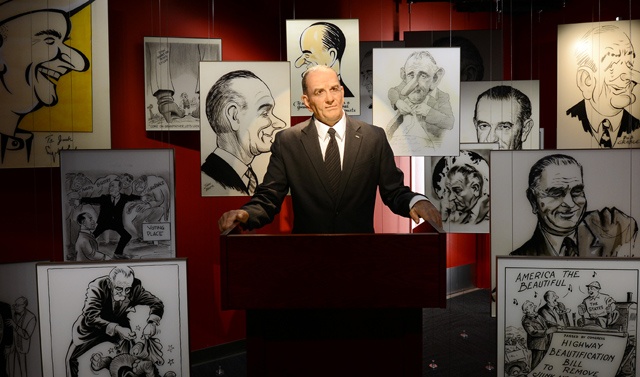

Each has its own personality. The LBJ library, the design of which the president had conceived just one month after he was elected to his first full term, is an imposing 10-story monument of white travertine on 30 acres that befits the namesake’s larger-than-life personality. The building boasts a giant lobby—called the “Great Hall of Achievement”—featuring a four-story glass wall behind which the archives are visible.

On the 10th floor is a replica Oval Office. Adjacent to it and not open to the public is a suite that includes a room that Johnson used as an office. There’s also a shower room that hints at how enamored with power Johnson was. It features a powerful array of mirrors and four industrial-strength shower heads, just like the ones he had installed at the White House that his successor, Richard Nixon, likened to bathing with a fire hose, Hufbauer says.

The domed, classical George H.W. Bush library is sprawling, with fountains and sculptures set on a 90-acre plot on A&M’s west campus. Its Oval Office replica is two-thirds scale. (LBJ’s Oval Office is seven-eighths scale, mostly because of ceiling limitations; W.’s replica office is actual size.)

Hanging overhead early in the exhibit is a full-size replica of the TBM Avenger torpedo bomber Bush piloted in World War II in which he was shot down, killing his crew. There’s a photo of a burr-headed Bush, looking more like a scared kid than a future president, being hustled into the conning tower of the submarine USS Finback seconds after being plucked from the Pacific Ocean.

There’s also Bush’s tribute to his first daughter, Robin, who died of leukemia at age 3 and inspired his postpresidency work to promote cancer research. Near the end of the maze of displays is a section of the Berlin Wall, one side covered in bright graffiti, the other pristine and stark, bearing mute testimony to why it stood and why it fell in 1989, the first year of his presidency.

The newest of the three libraries, George W. Bush’s, is a Georgian brick and limestone structure surrounded by a lawn of natural Texas grasses. It’s the first presidential library to earn a “new construction” Platinum LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification from the U.S. Green Building Council.

Not surprisingly, one of the George W.’s most evocative displays comes early in a tour of his museum, as it did in his presidency. Less than eight months into Bush’s first term, the terrorist attacks of 9/11 devastated the country. The centerpiece of the room is a twisted pair of steel beams from the twin towers of the World Trade Center.

Paul Goldberg, 65, visited the museum one Sunday last fall. He was a construction supervisor working on a public school building in Brooklyn that clear, crisp September morning in 2001. One of his crew noticed smoke billowing from one of the twin towers, which had moments before been hit by a passenger airliner. They all watched as a second plane hit the north tower. Goldberg closed the site, sending the workers home, but many, like Goldberg, stayed atop the school’s roof to watch the grim, stunning tableau play out.

“I’m the biggest flag-waver this country’s ever seen,” says Goldberg, who was visiting his daughter in Texas recently. “I did two tours in Vietnam. Anything to do with patriotism, I’m for. This is my country.”

A few days earlier, he had visited a different visceral presidential site a few miles down the road—Dealey Plaza, where President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed. “Next trip is to see the Alamo,” he added.

There are 13 official presidential libraries recognized and managed by NARA. There are also many that predate the Presidential Libraries Act of 1955, which created the federal presidential library system. These unofficial libraries are often operated by former presidents’ estates, hometowns or home states.

Hufbauer says the libraries are the manifestation of the “civil religion” of the United States, “that veneration that has existed since the country’s founding for particular events, people and things.”

Such as presidents.

LBJ was in office for 1,887 days; George H.W. Bush for 1,461. Only George W. Bush went out on his own terms—two of them, actually. LBJ finished Kennedy’s term and won re-election in 1964. Worn down by domestic strife and growing opposition to the Vietnam War, he declined to run again in 1968. George H.W. lost his re-election bid to Clinton in 1992, a defeat dutifully commemorated in a section of his museum that summarizes his loss: “In the end, the election was decided more on perception than anything else.”

In truth, leaving office might be the best thing to happen to a president’s image. According to a Gallup poll, of the last nine presidents, only LBJ and Clinton have a lower average approval rating after leaving office than they did while in office. LBJ slipped from 49 to 42 percent, Clinton from 66 to 60 percent. The first President Bush jumped from 56 to 66 percent, and

W. is up 13 points from his final 34 percent rating. Even Nixon is up nine points, to 33 percent.

Because presidential libraries are decentralized—each has its own site instead of being combined at a single site—and funded by NARA and private endowments, there is little control over what each library management wants to emphasize and omit or cast in a more favorable light.

The LBJ library has a section devoted to the acceleration of the Vietnam War. H.W.’s library mentions how Bush was portrayed as out of touch on the economy. The W. has an interactive exercise that portrays his decisions on Hurricane Katrina, the Iraq War and other key policy decisions as being well intentioned considering the information available at the time.

The LBJ and the first Bush libraries each underwent major renovations since 2007, and administrators at each say image burnishing is not high on the list of priorities.

Harry Middleton was the LBJ library director when it opened in 1971. “Years later, he has said that the more years that pass, the more objective a presidential library becomes,” says Anne Wheeler, the library’s communications director.

Holzweiss says the approach at the George H.W. Bush library is to be as objective as possible. “He’s said to me directly that he would like history to be the judge, warts and all,” Holzweiss says. “Put all the documents out there and let the people judge. We’re the facilitator, whether people come in and say ‘George Bush is a blankety-blank’ or ‘the greatest president who ever lived.’ ”

——————–

Mark Wangrin is an Austin writer.