Nothing speaks of home like a quilt, especially one with a family history. There’s something about the patching and stitching and padding that gives one comfort and joy.

A book, Texas Quilts and Quilters: A Lone Star Legacy, to be issued in October by Texas Tech University Press, has some wonderful stories about the roles quilts play in family life. Primary author Marcia Kaylakie, a quilt appraiser and collector, said her research has enlightened her to “how much Texas heritage is hidden away in closets, attics and trunks.”

While reading the book, I was especially taken with the stories of Osceola Dyer Woodruff, who spent most of her life in Red River County, and her daughter Zella Woodruff of Abilene. Osceola quilted out of necessity, saving tiny scraps of material and piecing them together because that’s the way things were done in her day. “Use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without,” the saying goes.

Kaylakie chose Osceola’s Dutch Doll quilt for presentation in this beautiful coffee table book. The Dutch Doll is a common pattern using a series of little calico figures in broad A-shaped dresses and sunbonnets (see quilt below). Osceola handed the quilt down to Zella, whose children called it “the sick quilt.” “When they were sick, Zella would sit beside them, making up stories about the little Dutch dolls, entertaining her children to keep them quiet,” writes Kaylakie. “These Dutch dolls went on great adventures while little fevered children listened to their mother’s soft voice soothing them, her cool hand testing their foreheads, settling them into the sheets so they could rest and be well. … This quilt made by a loving grandmother became a mother’s book of stories told during her children’s illnesses.”

After Osceola’s death in 1982, Zella discovered the true scope of her mother’s work, unearthing dozens of quilt tops she had never seen. Years later Zella took some of the tops to a shop to be quilted, and the staff encouraged her to learn to quilt them herself. “Zella found that quilting her mother’s quilt tops helped fill a void she’d felt since her mother’s death and also created lasting bonds with other quilters,” Kaylakie writes. As Zella said, “It soothed me to work on the quilts and helped give me comfort and ease my grief.” Comfort. Again, that word comfort.

Zella shared a great talent with her mother. “She decided she would make a quilt that would have special meaning,” according to Kaylakie. “She joined a quilt block exchange group, the Prairie Star Quilters. Each member contributed a block to Zella’s Precious Memories quilt. It includes many of Zella’s fabrics and her mother’s pieces of tatting discovered among the quilt tops and other needlework. “Precious Memories” (pages 14–15), with its pieces of silk, satin and velvet and heavy embellishments of lace, tatting, buttons, embroidery, ribbons and beads, was a finalist at the International Quilt Festival in Houston in 1999.

Quilt contests such as the one Zella entered didn’t start until the 19th century, and in the 20th century came the acknowledgement that the very finest are works of art. In the past couple of decades, as handmade products from China flooded the American market, it looked as if American quilting and quilt collecting might fall on hard times. But foreign imports can’t provide recreation and fellowship. Jean Yarborough of Jean’s Corner in Livingston says people flock to her store for lessons, material patterns and simply to exchange ideas. “The business is booming. People aren’t making quilts to sell. That would be too costly. They are made as art,” she says.

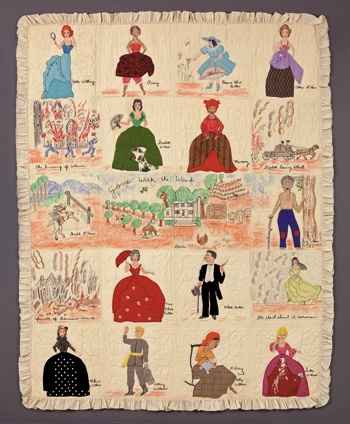

The specimens in Texas Quilts and Quilters represent a rich variety of handiwork. Predictably, quilts made from clothing scraps and flour sacks abound. But there are also tobacco-pouch quilts, with tiny pouches stuffed with cotton balls to make a “puff” quilt (page 12), also known as a biscuit quilt. In addition to traditional designs—such as the Lone Star, the Irish Chain, Four Tulips, Star, Dutch Dolls, Rainbow, Butterfly and so forth—the book also highlights unique quilts, including free-style “crazy” quilts. Several quilts have a cattle-brand motif (page 13), several have the signatures of high school classmates or church members, and one depicts characters and scenes from “Gone With the Wind” (page 13).

In addition to exhibiting beautiful photographs of 34 quilts taken by Jim Lincoln and his wife, Judy, the book, edited by Janice Whittington, provides histories of or interviews with the quilt makers and their descendants. The earliest quilts pictured are from the 1870s; the newest from 2003.

Kaye Northcott is the former editor of Texas Co-op Power.