Amy Von Lintel’s art history students need little guidance when she shows them Light Coming on the Plains No. III. The abstract painting consists only of an elliptical shape formed by darkening cool hues and bisected by a horizontal line of paper.

The West Texas A&M University students aren’t fine arts majors, but they recognize that image.

“I’m like ‘What is this? You guys know what this is,’ ” Von Lintel says of the 1917 watercolor by Georgia O’Keeffe. “The students know what a sunset and a sunrise look like here, and you put up an O’Keeffe that’s totally abstract. They’re like, ‘Oh yeah, she got it, and I get it.’ ”

O’Keeffe got it—the stunning way the sun breaks the horizon on the Staked Plains of the Texas Panhandle—because she lived it.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Light Coming on the Plains No. III.

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986); Light Coming on the Plains No. III; 1917; Watercolor on newsprint paper; Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas; 1966.31. © Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

One hundred years ago, O’Keeffe taught art on the same campus—years before her oil paintings would earn her the title Mother of American Modernism. O’Keeffe’s Texas landscapes hang in galleries nationwide, but only recently has her dazzling prose—preserved in dozens of letters and studied by scholars—allowed the artist herself to convey the feelings that colored the paintings and painter. Her words show a stunning well of creativity within a young woman who was figuring out life—and how to stay upright in the craggy paths of Palo Duro Canyon.

O’Keeffe spent only a few years in Texas, but it had a hold on her.

“There is something wonderful about the bigness and the loneliness and the windiness of it all,” O’Keeffe wrote to a friend. “I like it so much that I wonder if it’s true—The country is almost all sky—and such wonderful sky—and the wind blows—blows hard—and the sun is hot—the glare almost blinding—but I don’t care—I like it,” she wrote another.

Friends in New York City supplied O’Keeffe with books and prints of textiles and pottery for her Canyon classroom.

Courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

‘Kick Your Heels in the Air’

Many decades before she would be hailed as “the undisputed doyenne of American painting” by The New York Times, O’Keeffe needed a job. That’s what brought her to Texas from Virginia in 1912, when the 24-year-old artist took a job teaching art in the Amarillo public school system. She had never been to Texas, knew no one when she arrived alone and had never taught.

She took to the place and the work. “Pretty soon, I got so interested in teaching I wondered why I should be paid for it,” O’Keeffe said in a 1974 interview.

In 1914, she relocated to New York City and expressed jubilation in 1916 when she was offered the job as head of the art department at what was then West Texas State Normal College, in Canyon, south of Amarillo. The Wisconsin native who had studied in Chicago and Virginia and taught in South Carolina was headed back to the Panhandle.

“Kick your heels in the air!” she wrote to a friend. “I’ve elected to go to Texas.”

‘Big Quiet Moonlight’

A decade ago, Von Lintel needed a job. When West Texas A&M University offered her a position in O’Keeffe’s former department, the Kansas City native, who studied in California, moved her family to Amarillo. She had never lived in the Texas Panhandle and had never studied O’Keeffe.

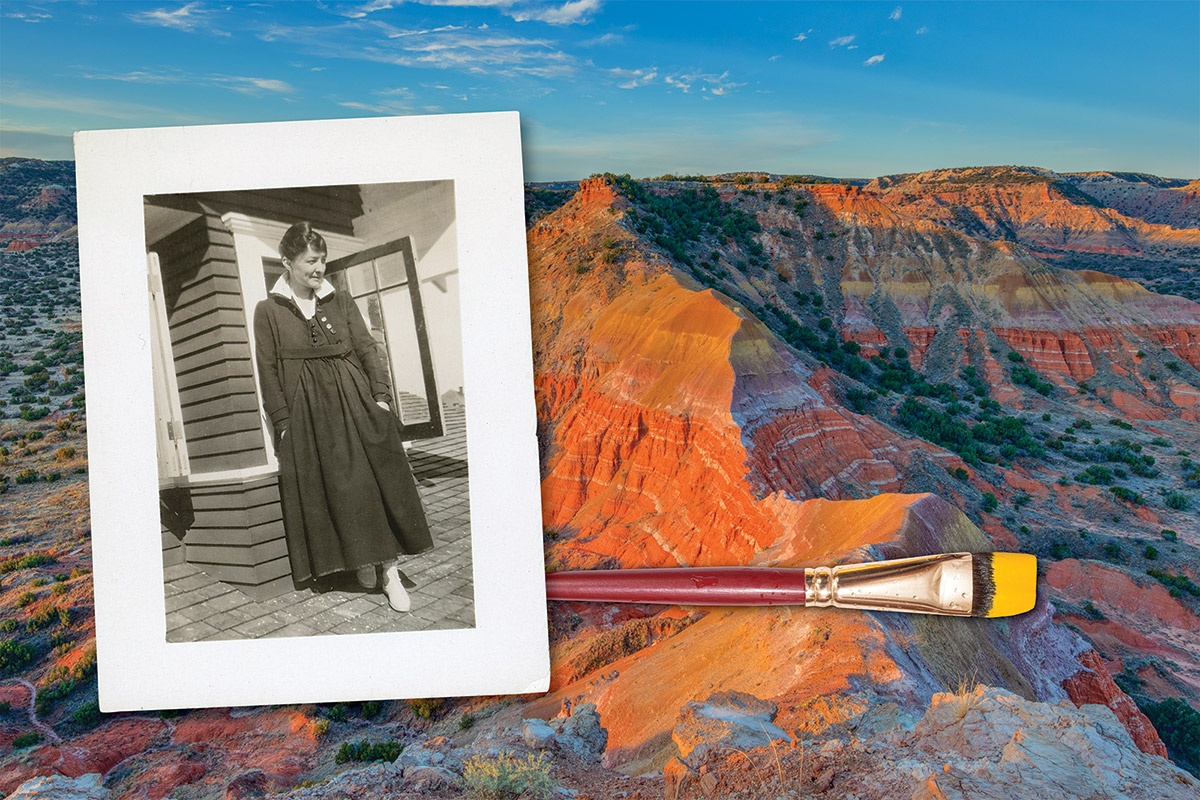

Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1917 yearbook photo.

Courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

“I think the thing that also led me to study her is this strange connection of being in the department that is hers,” Von Lintel says. “It takes some bravery to move into the middle of nowhere and fall in love with it, and I think she did.”

O’Keeffe is still present in the Panhandle. The Amarillo Museum of Art and the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum display her works.

“Canyon is very aware of its history with Georgia O’Keeffe,” says Carol Lovelady, PPHM director. “It’s a tremendous point of pride for the museum and for Canyon.”

The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, near where the artist spent her later years, houses many of her works, but her letters are kept at Yale University.

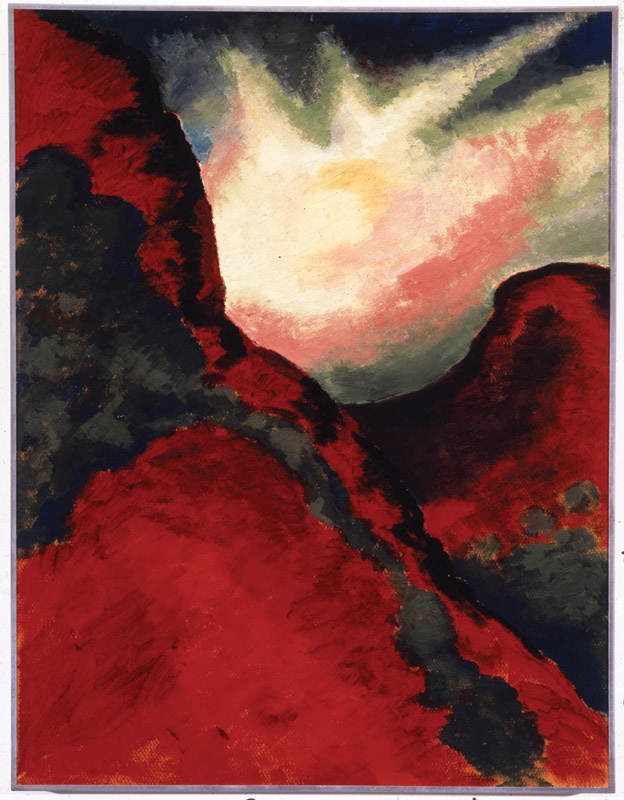

Red Landscape is on display at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Red Landscape, 1916–1917, Oil on board, courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

The trove is mostly correspondence between O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz, the New York City photographer whom she married in 1924. The letters were unsealed in 2006. In them, “She talks about abstraction, about how her mind works and about how she makes a piece,” Von Lintel says. “We learn about her technique, we learn about her thought process, her frustrations of like, ‘I’m seeing this form, but I can’t get it right.’ ”

The dozens of letters recorded life among the vestiges of the Old West: Texans coming to terms with a world at war and life as a 20-something who spent her free time not just painting on front porches but also shooting rifles, riding in cars with boys and walking for miles on end.

“It’s a wonderful night—still and warm and moonlight—big quiet moonlight—As I walked home alone in it—I was tired,” she wrote Stieglitz. “… I think the best way I can tell it to you is—that last night I loved the starlight—the dark—the wind and the miles and miles of the thin strip of dark that is land.”

Hikers in Palo Duro in the 1910s.

Unknown photographer. Group Hiking in Texas, ca. 1912 / 1918. photographic print. Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation Photographs. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation

‘So Big and Impossible’

Von Lintel began studying the letters in 2011, using them to assemble a timeline of O’Keeffe’s time in Texas. That work culminated in her book, Georgia O’Keeffe’s Wartime Texas Letters, published in March. The professor sought to empower the artist to tell her own story.

“I wanted her to just kind of stand on her own because when she was out here, she was on her own,” Von Lintel says.

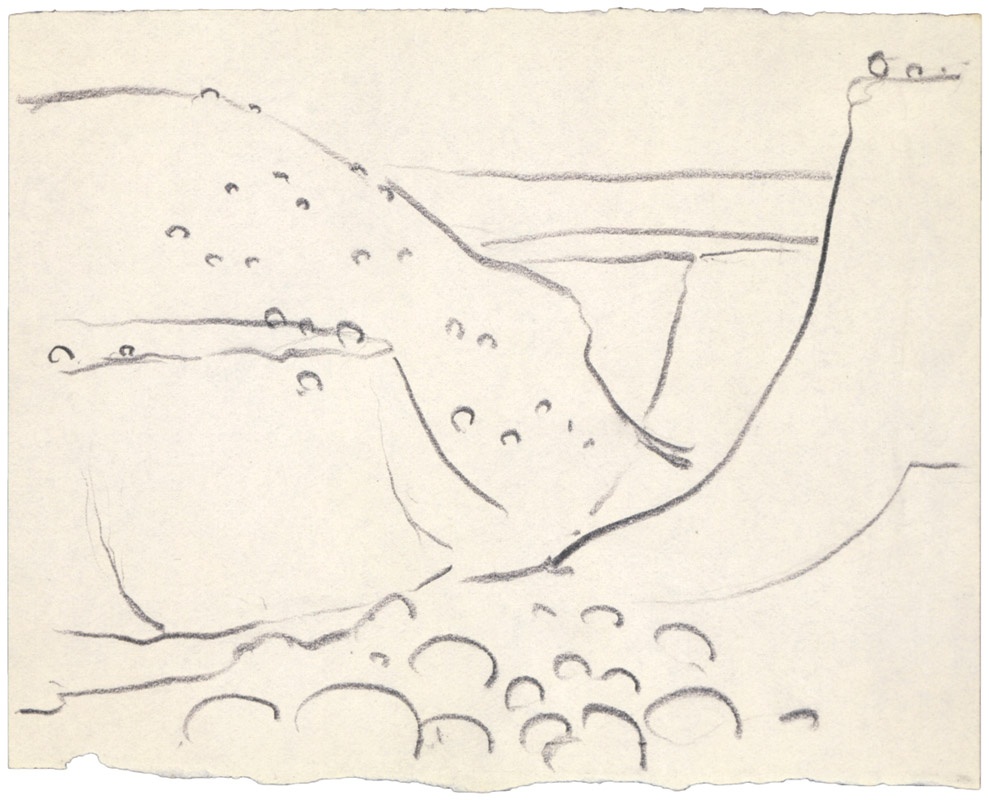

The letters trace the feelings that shaped O’Keeffe’s early paintings, some of which feature 800-foot-deep Palo Duro Canyon—what she called “a curious slit in the plains.”

O’Keeffe explored the canyon with fervor, writing of it in many letters: “Yesterday was sunny and fine and I went to the Canyon again—about twenty miles east—climbed and scrambled about till I was … out of breath many times over—and felt very little—such a tiny little part of what I could see had worn me out—Yes—I was very small and very puny and helpless—and all around was so big and impossible.”

Those “big and impossible” feelings are apparent in O’Keeffe’s 32 canyon works—many of which include imposing forms and dark colors, including deep reds. And while the iron-rich walls of the place do bear a reddish tinge, O’Keeffe’s feelings bore the rest.

“What she liked here were people that she felt like had a lot of red in their blood,” Von Lintel says. “Red-blooded, vibrant people who go outside, who stand in the light and live their lives.”

‘Terrifically Alive’

In April 1917, O’Keeffe opened her first solo show, in New York. She also sold her first piece, a charcoal drawing of a Panhandle train, which she described in a letter: “A train was coming way off—just a light with a trail of smoke—white—I walked toward it—The sun and the train got to me at the same time—It’s great to see that terrifically alive black thing coming at you in the big frosty stillness.”

Von Lintel hopes her students, through O’Keeffe, can see the beauty right in front of them.

“One of the things I always do is connect whatever I’m teaching to the local area because students should learn to look around themselves and see art and beauty here,” she says. “It’s not like we’re in the middle of nowhere.”

Chris Burrows is a TEC senior communications specialist.