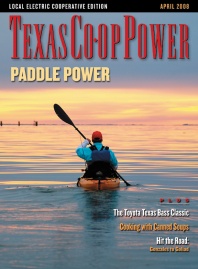

Boats tend to shrink in relation to the size of the waters they occupy. By that measure, my 12-foot kayak might as well be a dried-out oak leaf drifting across the mirrored, sprawling surface of San Antonio Bay north of Rockport.

Piled atop the horizon like a mile-high cluster of stained and waterlogged cotton balls, a colossal, anvil-shaped thunderhead is slowly sliding across the expansive mid-coast bay’s easternmost fringe. Mercifully, the storm is headed offshore. Sunlight leaks through thin blue cracks in the clouds, each one spilling pastel streaks of pink, orange and purple onto the shimmering bay’s shallow and reef-laced waters.

Come springtime on the Texas Coastal Bend, mountainous cloud formations such as this are classic early morning signatures. Montana, it’s safe to say, holds no monopoly on “Big Sky Country.”

From the tiny village of Fulton down State Highway 35 through Rockport—and farther to the south, the waterfront communities of Aransas Pass and Port Aransas—it must be virtually impossible not to see the swollen and billowing squall line vividly punctuating the advent of the late-April sunrise.

Seeing an angry weather system from the ground is one thing. Observing it from the plastic seat of a kayak smack-dab in the midst of a gargantuan lagoon is altogether another.

I could just as easily be viewing the super-sized seascape from my vee-hulled fiberglass bay boat, the same 21-foot rig that transported my kayak across Aransas Bay, up the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway past Ayers Dugout, into the entrance of Mesquite Bay north of Cedar Bayou and beyond.

Still, the encounter wouldn’t be nearly the same. Not by a long shot.

The intimacy of coastal kayaking is indescribable, particularly to those who have yet to experience it. Not surprisingly, the number of enthusiasts who regularly enjoy the peaceful, calming serenity of open-water paddling is rising like an incoming storm tide.

According to the Outdoor Industry Association, kayak participation nationwide doubled in the six-year span between 1998 and 2004. On the Texas sport-fishing front alone, some 2,000 new participants a month are entering the vast and amazingly untamed arena of saltwater angling. Motivated by a variety of reasons, from featherweight, near-effortless portability to remarkable affordability, a rapidly increasing number of the state’s rod and reel-wielding newcomers are taking to the bays and flats via kayak.

Be it on the Coastal Bend, Baffin Bay or the Lower Laguna Madre, shallow-water gamefish are extremely skittish creatures. For the half-million-plus Texas anglers who avidly pursue redfish, speckled trout and other popular inshore species, kayaks are the boating equivalent of stealth fighters.

All the same, despite their surging popularity as angling platforms, the scope and utility of the diminutive paddle-powered boats infinitely transcends the quest for the perfect catch. Coastal kayaking possibilities are as limitless as the water.

Silent as the wind, unexpectedly stable, light enough to navigate otherwise inaccessible habitats and incredibly durable, modern “sit-on” kayaks open seamless natural windows to a mind-boggling array of shorebirds and scenery.

For many, kayaking is not so much a sport as it is a spiritual retreat. It’s intriguing, even awe-inspiring, to stab a sharp-bladed paddle into the olive-green waters of the same coves, flats and tidal pools that centuries ago were probed by canoeing tribes of Karankawa Indians.

No matter the mission, whatever the motivation, ocean kayaking has become the fastest-growing water sport on the western Gulf Coast. What was once an oddity is now an obsession for tens of thousands of devoted saltwater paddlers.

Elsewhere this morning, a rainbow-hued armada of dedicated kayakers is tracing the shorelines and inlets of the Coastal Bend. Some rented their craft. Others brought their own kayaks and launched from a host of points that grant easy access to paddle-friendly locales. Yet others, yours truly included, launched their “big boats” solely as vehicles to transport their favorite kayaks.

A well-known bird-watching boat, the 40-foot-long Skimmer, provides yet another option to intrepid Rockport-area kayakers. Owned and operated by Capt. Tommy Moore and moored at Fulton Harbor, the touring vessel doubles as a kayak transport on select bay excursions.

Drawing a scant 2 1/2 feet of water, Moore’s “mothership” (continued on page 14) (continued from page 12) ferries kayakers across Aransas Bay to remote locales on the grassy outside fringes of San José Island. For paddlers who don’t own bay boats to carry their kayaks, the Skimmer presents a first-class ticket to isolated getaways that teem year-round with native and migratory wildlife.

Some Skimmer passengers bring their own kayaks. Others rent from Moore. Either way, no matter how it’s procured, no matter where and how it’s cast adrift, a quality kayak reserves a unique front-row seat to the Texas Coast’s most enthralling vistas.

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s Coastal Paddling Trails represent some of the finest. TPWD offers maps for each of the seven existing trails, and all are marked with signage to help novice explorers stay on the right track.

The department website (www.tpwd.state.tx.us) contains a wealth of information, including a comprehensive list of the existing trails and details on each, put-in and takeout points, GPS coordinates, water-safety advice, maps and helpful references to kayak-related reading materials and resources.

Bob Spain, TPWD coastal conservation coordinator, is the state’s leading authority on the Coastal Paddling Trail network. “Our goal is simply to provide more recreational opportunities for the public,” Spain said. “Many of our areas, like the Lighthouse Lakes Paddling Trail near Aransas Pass, are ecologically sensitive. Kayaks allow visitors close-up but low-impact looks at the habitat. Aside from that,” he said, “they let their occupants see wildlife that they’d never get the chance to see from a boat with an outboard engine.”

The nonchalant demeanor of a mature great blue heron prowling the bank less than 30 feet away is living testimony to Spain’s assessment. Tiny whirlpools spin outside the paddle blades and funnel past the stern as I quietly enter the regal shorebird’s territory.

The closer I get, the more I realize how tall a full-grown heron stands. Then again, it may just be that this little red boat of mine seems smaller than ever.

——————–

Journalist and photographer Larry Bozka of Seabrook is an expert on salt-water fishing.