This is the story of the little stream that could.

Close your eyes and imagine a quiet place 200 years ago on the banks of an idyllic waterway in the southeast part of what would become the state of Texas. There’s a stream flowing quietly, with the occasional protruding tree trunk beneath overhanging cypress branches, its water so clear the buffalo fish are visible from its banks. It’s nothing to behold in terms of grandeur, just about 60 yards wide and 15 feet deep, but there’s an inexplicable sense of untapped potential.

Next put your nose and ears to work. There’s a whiff of magnolia cut with the faint scent of a dying sea breeze. There’s the hoarse honking of herons and the barely audible sound of Karankawa braves paddling past in a dugout canoe.

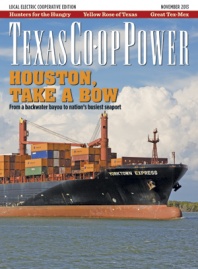

This is Buffalo Bayou. Or was. Open your eyes and take a look now. Snaking its way toward the Gulf of Mexico is a 52-mile-long channel, its waters roiled with the prop wash of 100,000-ton oil tankers and its banks crowded with cranes, wharves and warehouses as far as you can see. The 130-decibel air horn of a freighter bullies the air, punctuating the sounds of whirlwind commerce. The magnolia smell has given way to an industrial potpourri of diesel fumes and other petroleum production vapors and, yes, an even fainter whiff of a sea breeze.

What used to be a simple stream is now, two centuries later, part of an enormous complex of waterways and infrastructure known as the Port of Houston, which helps drive the Texas economy. As the busiest seagoing export port in the United States, it generates more than 1 million jobs and pumps more than $178.5 billion into the statewide market, including $4.5 billion in state and local taxes, according to a 2012 study by John C. Martin, a maritime transportation economist. Next November will mark 100 years since the deepwater Port of Houston opened for business.

Not bad for a little stream.

“It is a fascinating story,” says author Mark Lardas, who wrote about the port and the movers and shakers behind its development in “The Port of Houston” (Arcadia Publishing), due out this month. “In many ways, the Port of Houston is a metaphor for the story of Texas in that they put it together with hard work, risk-taking and a little bit of Texas brag.”

What they created was a magnet for international business that put Houston on the map. It easily could have been Harrisburg, a few miles downstream, or Galveston, where the bayou eventually empties into the Gulf of Mexico through the state’s only true deepwater harbor, if not for vision, salesmanship, innovation, serendipity and more than a little politics and pluck.

John Kirby Allen and Augustus Chapman Allen, land speculators and brothers from New York who sought to establish a city named after the great hero of the Texas Revolution in the late 1830s, had the salesmanship. They also had the vision. The Allens saw plenty of opportunity, not in the plush, verdant banks of Buffalo Bayou, but in the potential for money, easy and quick. “They weren’t thinking this was one day going to be the fourth-largest city in the United States,” Lardas says. “They just thought, ‘Oh, gee whiz, this is a good spot to build a city, sell some land, and get out of here.’ ”

It didn’t hurt that the Allens also were adept at that time-honored tradition of backroom dealmaking, donating land and construction in Houston to build the new republic’s capitol. They also helped build the image of Houston as the state’s potential dominant port by dubiously claiming that the head of the waterway that leads to Galveston Bay was near Houston, not Harrisburg.

Top trading partners in 2012 based on combined imports and exports, by tonnage: Brazil, China, India, Russia and Germany

But when the railroads came in the 1850s, and getting cargo to and from Galveston became easier, the potential for Houston to become a seagoing city was at a precipice. “Houston really had a problem,” quips Lardas, who worked as a NASA contractor at the Johnson Space Center for 25 years. “Unless they could turn it into a deepwater port.”

One of the local newspapers, the Weekly Telegraph, forewarned in 1867, “Houston, with the ship channel, is the favorite commercial point in Texas; without it she is a small commercial town gradually growing up by her railroads and manufactories, but destined never, in our lifetime, to grow very much beyond what it is now.”

So deepwater it was. And when the cities of Galveston and New Orleans rubbed Charles Morgan, the top shipper in the Gulf of Mexico, the wrong way with their methods and taxes, he snatched up companies and land, and in the 1870s dug a private canal to give Houston the upper hand. In 1900, a powerful hurricane devastated Galveston, and 12 years later, work began to dredge a deep channel from Houston to the Gulf. Game over.

“Houston and Galveston were kind of like brothers who quarrel with each other, depend on each other, but really don’t get along,” Lardas says.

Technology tells the story of how Houston dominated the Galveston port, and ultimately the nation’s ports. When the railroads came in and a deepwater port was needed, Houston already had the dredging capabilities. When the triple-expansion steam engine, which allowed ships to recycle steam for power two more times, came into use in the 1890s, going the additional 50 miles from Galveston to Houston became more efficient.

Would anyone believe in 1836 that Houston would be the largest seaport in the United States? Lardas asks. “I don’t think so, but the reason it is is technology,” he says. “It seems every time there’s a technological revolution, it seems to end up helping Houston.”

Top commodities in 2012 based on combined imports and exports, by tonnage: plastic, petroleum and petroleum products, organic chemicals, iron/steel products and miscellaneous chemical products

Now the recent development of profitable methods to squeeze oil and gas out of oil shale, such as hydraulic fracturing—fracking—is allowing Houston to again experience an oil and gas boom.

“Last year, we had a record year in steel piping,” says Bill Hensel, director of corporate communications with the Port of Houston Authority. “This year there’s a big gain in oil exports. That’s all because of fracking.”

Economic factors also made a huge difference through the years, Lardas says. When the Great Depression hit and unemployment soared, many people made ends meet by buying cheap trucks and using them to carry cargo to ports. Houston was closer to the supply than Galveston, and fewer miles to drive meant more profit. When containers cut the cost of shipping in the 1950s and ’60s by 97 percent, Lardas says, union longshoremen in other ports nationwide refused to unload them because they required less labor. Houston’s port wasn’t fully unionized. Houston won again, and it hasn’t let up much since.

Bill Diehl, retired Coast Guard officer and former captain of the Port of Houston, is now director of the Greater Houston Port Bureau. “People never think of Texas as a maritime state,” Diehl says. “Our ports are our on-ramp to the global economies. Big companies across the country are looking to expand to other countries. We’re well positioned for that, and if you don’t sell to the whole world, someone else will.”

The port bureau acts as a clearinghouse for ship movements and port promotion. “We’re the 411 for the port,” Diehl says. It’s important to stress the economic impact of the Port of Houston because ports are often overlooked when state politicians are doling out funding, he adds.

With $110 billion in exports in 2012, the Port of Houston became No. 1 in the United States, surging past the 2011 leader, the Port of New York and New Jersey, by $8 billion. The 5.6 percent rate of growth also topped all domestic ports, according to data from the U.S. Department of Commerce released in July.

The Port of Houston is preparing for more growth. Expansion of the Panama Canal, which cut through the 48-mile-wide Isthmus of Panama in 1914 to allow ships to bypass the treacherous and lengthy trip around the tip of South America, began in 2010 and is expected to be finished next year. The $5.25 billion project will widen and deepen the channels and replace existing locks with larger ones to allow bigger ships to make the crossing.

Meanwhile, Houston again must resort to technology to catch up. Rather than wade through government bureaucracy that might delay the project a decade or more, Diehl says, the port is using money from its own version of a rainy day fund to pay for the dredging of offshoots of the lower ship channel to accommodate the bigger ships, which draft at least 45 feet, 5 feet more than the current depth.

Houston has an inherent advantage over ports where the dredging depth is limited, Lardas says. “The only thing at the bottom is mud,” he says. “Bedrock is at least 300 feet down. The problem is, once again, technology. You roll the dice one more time, and so far it’s been a winner every time.”

Companies interested in keeping the Port of Houston vibrant aren’t shying away from investing in the future, according to a port bureau survey that drew responses from 39 percent of those firms. The study reveals known investment of $28.8 billion in improvements between 2010 and 2015. Martin Associates, which conducted the Port of Houston economic impact report, estimates the investment will lead to 111,700 direct construction jobs, 154,100 induced and indirect jobs, and $800 million in tax revenue from 2012-15.

“The best thing about the Panama Canal expansion is that it’s not going out of business,” says Diehl. “The ships are getting bigger. If you’re not able to handle bigger ships, you go out of business.”

Diehl expects the state’s oil shale plays to allow Houston to again get ahead of the curve. Oil companies along the ship channel have been refitting to handle the expected flood of natural gas exports.

And if some future technology creates a way to ship goods cheaper? It would be time to adapt once again—employ the vision, technology, verve and innovation that got the Port of Houston where it is today, on the verge of its 100th birthday.

It’s an unlikely story, how a small inland stream near a town named after the first president of the Republic of Texas, neither of which were given much of a chance for success in their infancies, not only survived, but prospered and ultimately dominated. It’s the story of Texas, a microcosm of how the state overcame seemingly insurmountable obstacles to get where it is today, and it all began with a stream and a dream.

——————–

Mark Wangrin is an Austin writer.