Native Texan John P. O’Neill is the rarest of birds: a world-renowned zoologist whose Audubon-esque expeditions and paintings draw comparisons to the great American naturalist.

Bird artists commonly are measured against Audubon, whose works remain the benchmark for ornithological illustrations. But for most painters, the similarities stop with the brush strokes.

Enter the 70-year-old John Patton O’Neill, who like John James Audubon, spent his career in the field. For almost half a century, starting in 1961, O’Neill explored the jungles, mountains and cloud forests of Peru, observing some of the world’s most secretive birds. Like Audubon, O’Neill’s discoveries—14 species of birds, all in Peru, and the most recorded by any living person—were new to science. And like Audubon, his view of the birds as depicted in paintings is how they were presented to science.

O’Neill’s paintings have graced the pages of the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, the modern-era bible for birders. And his influence is seen at Louisiana State University, where he earned master’s and doctoral degrees in zoology with a specialty in ornithology. Thanks to O’Neill’s research, the LSU Museum of Natural Science, which he directed from 1978-82, boasts the world’s largest collection of Peruvian birds.

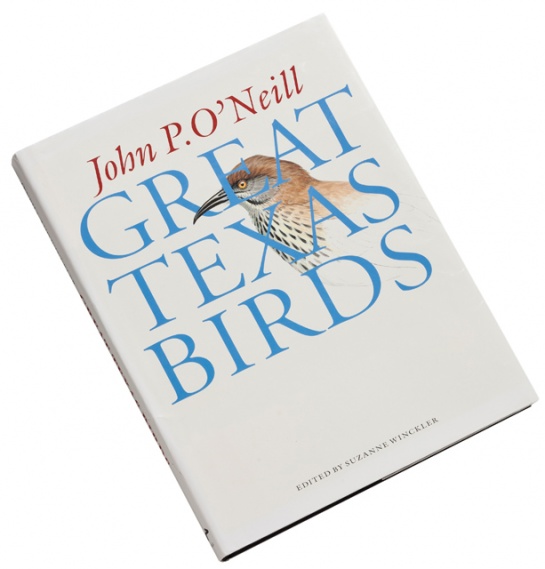

Rarely has a life been so beautifully painted—which makes it even more intriguing to look back at the undeveloped woods of west Houston and the messy canvas, as it were, of a wild-hearted boy in love with nature. It was there that O’Neill planted the seeds for Great Texas Birds (University of Texas Press, 1999), the book so exquisitely reflecting his belief that all birds are wondrous creatures.

At the age of 5, O’Neill gave his mother his first illustration: an oil painting of a bantam chicken. He roamed fields and woods, studying birds. He raised baby ducks and let them swim in the bathtub. And he dismayingly watched his father clean ducks after hunts: The boy wanted the beautiful birds’ feathers left on so he could paint them.

Today, O’Neill and his wife, Leticia A. Alamía, a fellow ecologist and zoologist, monitor the wildlife of the Rio Grande Valley, where they are members of Magic Valley Electric Cooperative. In March, the couple moved to Hidalgo County from Anderson, near College Station, where they were served by Mid-South Synergy.

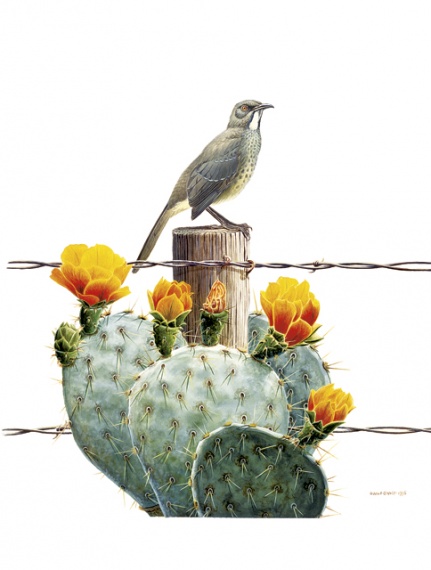

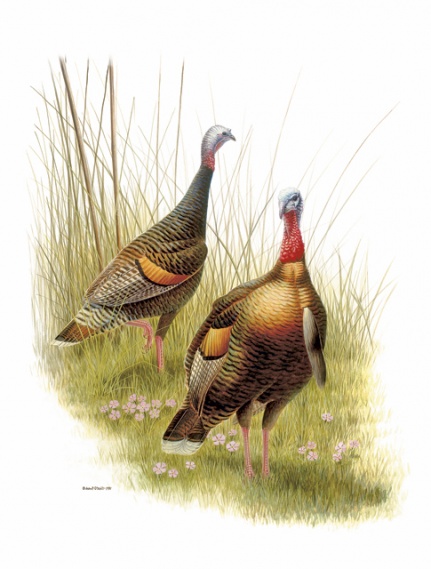

O’Neill, who continues to recover from a stroke he suffered in 2008, hopes to next produce a book of paintings of Rio Grande Valley birds. For now, we invite you to enjoy four illustrations from Great Texas Birds, which showcases 48 of Texas’ almost 640 official species alongside native plants specific to that bird’s habitat. Essays from native Texas naturalists (see illustration above and illustrations in slideshow presentation) mirror O’Neill’s passion: All birds—from the Least Tern to the Greater Roadrunner—are magnificent.

O’Neill floods his paintings with light, revealing feather colors that change, depending upon time of day, in brightness and hue. On this artist’s canvas, no bird is left in the dark. No bird is left behind.

——————–

Camille Wheeler, associate editor