Near where Fort Concho soldiers once guarded the West Texas frontier, a former Marine in his first year back from Afghanistan mans the front desk of a small veterans assistance office in downtown San Angelo. He’s one face of today’s young war returnees readjusting to civilian life, but this veteran is far more fortunate than others who’ve come home without job prospects and with recurring psychological difficulties.

Hundreds of miles away in East Texas, a middle-aged lineman for Sam Houston Electric Cooperative recounts how he made the transition back from the horrors of Iraq. With a family and a welcoming workplace awaiting him, he found comfort in daily life far from the violence he survived. Other veterans in the same town of Livingston are not doing so well.

As thousands of veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan return to the United States and leave the service, they face a trying battle over diagnosis and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorders and traumatic brain injuries. Veterans seeking help for these conditions from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs must wait for a year or more on rulings from the overwhelmed federal agency. To help reduce the 107,000 disability claims in Texas, the Texas Veterans Commission is adding 24 counselors.

As an independent advocate for veterans, Laura Serrano works on claims from the San Angelo area every day in her cramped, unadorned offices across the street from the Tom Green County Courthouse. At this veterans center operated by the county and the Texas Workforce Commission, former service members discuss claims and appeals filed with the VA.

“Claims are my passion,” says Serrano, who served in the Army in the 1990s. She talks fast amid a whirlwind of calls and visits from veterans of all eras. She tells younger vets “to honor and respect what they have in benefits available to them that have been handed down at some cost from previous generations.”

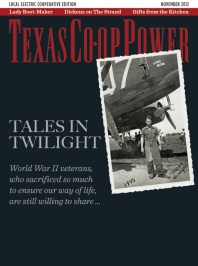

Indeed, many World War II veterans have tremendous sympathy for those who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan and have been subject to multiple deployments. “We went to war, and when it was over we came home. They are back home a short time, and they are back over there again. This goes on and on, and sooner or later you are going to get killed or get a leg blown off,” says Marion Henegar, 95, a World War II veteran who lives in Livingston. “It’s terrible.”

The VA claims process became a logjam in the past couple of years because at the same time new veterans filed disability claims at a greater rate than from previous wars, the government in 2010 began recognizing more health conditions for Vietnam vets.

Assisting Serrano and the county veterans service officer who shares the offices is Hunter Granzin, 22, who in 2011 was a Marine driving M88 recovery vehicles to pick up damaged tanks and Humvees in Afghanistan. Now a student at Angelo State University, he works part time at the office.

Granzin grew up in nearby Miles and looks young enough to still be stocking the shelves of his father’s grocery there. He says he isn’t suffering mental health issues from his combat experiences, but that’s not the case with a friend who also drove an M88. “He had to recover bodies and kill people firing on his convoy. Now he has survivor’s guilt, emotional problems, dreams about it,” says Granzin. “At first he didn’t want to claim PTSD because he thought people were using it as a crutch. But now that he sees it happening to him, he realizes it’s real.”

Granzin concentrates on his job and school. “It’s something to get up for every day. They keep me from getting too depressed about the abrupt lifestyle change from Afghanistan to home.”

That tough transition is the target of the Texas Veterans Leadership Program, which has 18 employment counselors, all Iraq or Afghanistan veterans, in offices around the state. Begun in 2008 under the Texas Workforce Commission, the program primarily helps vets prepare for job searches. It also steers them toward mental health services.

Steven Goligowski, who retains the bearing of an Army officer, retired after a 28-year career, which included three tours in Afghanistan and Iraq. He is the Leadership Program representative for the San Angelo area. “The No. 1 obstacle I see with veterans getting jobs is they [vets] tend to have a pretty narrow view of their talents and abilities coming out of the military,” he says. “They do not understand they could get work with their financial management skills, their property accountability, their personnel management.”

He advises vets to lose military jargon on their résumés and use terminology relevant to civilian jobs. A squad leader who directed a team of soldiers, for example, managed people just as a line supervisor might at a manufacturing plant. He also counsels vets on how to establish proper workplace relationships once a job is landed. For PTSD sufferers, Goligowski and Serrano recommend VA-approved cognitive behavior therapy programs to help fight debilitating symptoms.

In Livingston, a town of 5,500 people northeast of Houston that is home to Sam Houston Electric Cooperative, two post-9/11 veterans meet each other for the first time at the county annex building. This is where Melissa Gates offers assistance as the county’s veterans service officer.

Christopher Mizell, 33, tells his story first. The Army mechanic collapsed outside his sleeping quarters in Iraq one evening in 2008 during his second tour there. He was evacuated for treatment and sent home. “I was told I had seizures, though I never had one before in my life,” says the father of two young children. “Maybe it was because I figured it was my last deployment. I couldn’t take a lot of it anymore.”

Mizell left the Army and had been frustrated at not being able to get a steady job until this summer. He started July 1 as a mechanic for the Texas Department of Transportation in nearby Shepherd. Previously he had lived on his wife’s income and compensation payments for his 30 percent disability rating for back and hearing problems and PTSD.

“It’s hard finding a job,” he said before landing the full-time position. He said he had “looked everywhere. But I don’t think people want to deal with soldiers having PTSD.”

Sitting near Mizell in a conference room is 27-year-old Wes Templeton, who served in the Army infantry in Iraq and Afghanistan between 2005 and 2010. He says he still has severe sleep problems—“waking with cold sweats and nightmares. It’s just ridiculous.”

He has a 50 percent disability rating from the VA for back, shoulder, foot and hearing problems but awaits a ruling on a new claim for PTSD.

Templeton has some training as an auto mechanic. “I filled out job applications just about everywhere. A lot of times they just don’t call you back. You check that you are a veteran or give them a copy of your discharge, but nothing.”

The majority of veterans of recent wars are more fortunate in their transitions to civilian lives. Less than a mile from where Mizell and Templeton discussed their situations, Army reservist Yancy Williams talks about his return from Iraq in 2009 to his family and job at Sam Houston.

The 45-year-old lineman relates his military police experiences in the dangerous city of Mosul to his work with power lines. “Taking shortcuts can get you killed,” he says. “You have to stay aware and use your safety equipment. It’s all about training and knowing you can rely on the guy next to you.”

Williams’ eyes glaze over but his voice is steady as he details the carnage he witnessed on the busy streets of Mosul. Once, a 2,000-pound bomb went off on a flatbed truck near where he was patrolling, leaving a hole deeper than his 6-foot-2 frame: “Body parts were all over the place, pieces of people everywhere, civilians and Iraqi military. We dug through rubble, but there was little we could do.”

Williams, the son of Polk County’s first African-American sheriff’s deputy, says he was able to handle war without nightmares or PTSD because as a longtime volunteer firefighter, he’s seen gruesome fire deaths and wrecks. “I prayed, and having a spiritual balance helped me a lot. Very few guys around here can really understand what it smells like over there, know what it sounds like, know what it feels like.

“I’m fine now,” he says firmly, noting the backing of “my best support system”—his wife of 25 years, Tammy.

Williams recognizes jobs are hard to come by and says, “I couldn’t ask for anything better than working at Sam Houston.” He started at the co-op in 1991 after a tour of duty in the Marines serving in Panama and Europe. In 1993, the lineman joined the Army Reserve, and his unit was called up for a year to help NATO forces end the ethnic warring in Bosnia.

The co-op held his job for him, with no loss of seniority. “This company has been so supportive of my being in the reserves,” Williams says. “I know guys at other companies who have had jobs and they get back with no work for them, and it’s ‘Too bad, so sorry for you.’ ”

Kyle Kuntz, CEO of Sam Houston, praises Williams as “a great employee with a really good attitude.” Turnover is low among the co-op’s 160 employees, and Kuntz says he gets to make only one or two hires a year. But he says the responsibilities carried by troops means “if you have two equal applicants and one has been in the military and one hasn’t, typically we’d go with the one who’s been in the military.”

As for the thousands of backlogged VA claims, Williams says, “They just don’t have the number of people or the budget they need. I don’t think they prepared for what was coming their way with the war, how long it would last and how many people would need help.”

He worries that over time the physical and mental tolls on veterans will increase. “If they don’t care for these young guys now, you just don’t know. …” he says. “I think the veterans, the guys who were willing to lay it out and go over there for our country, should get whatever they need, whatever they want.”

——————–

Ed Crowell is an Austin writer.