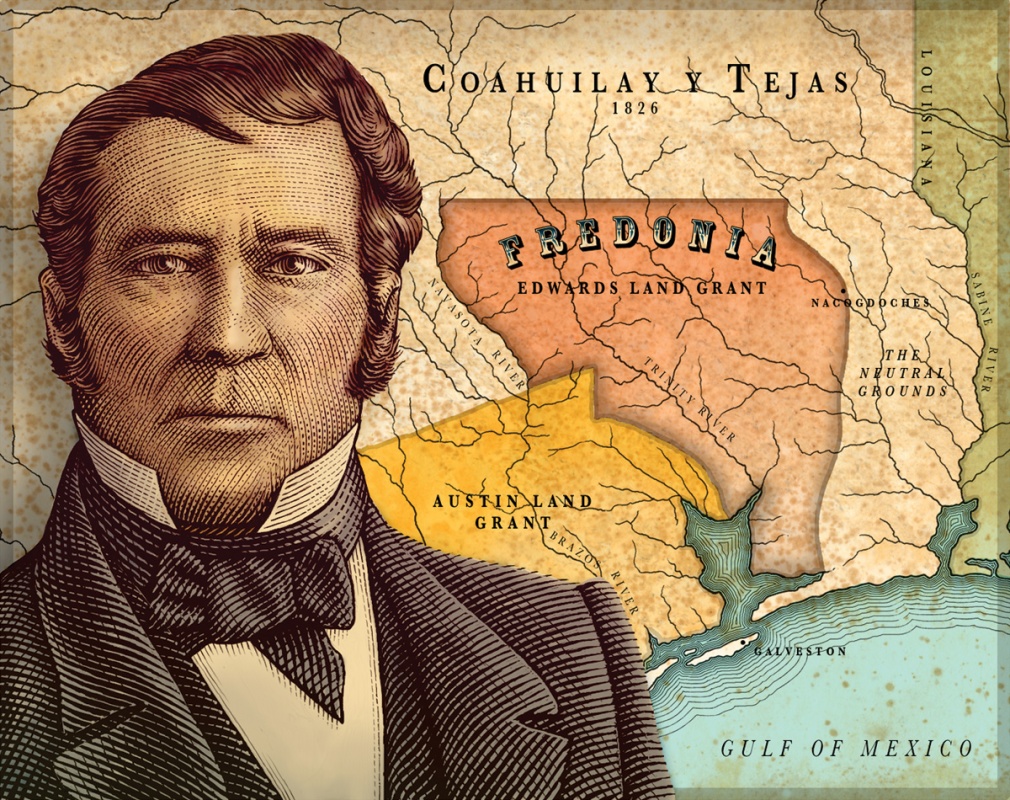

An uprising near Nacogdoches in 1826 foreshadowed the Texas Revolution years before Sam Houston’s army defeated Mexico’s forces. In September 1825, empresario Haden Edwards acquired a grant from Mexico to settle 800 families in an area of East Texas that included Nacogdoches. Edwards’ contract allowed the settlement to be “bounded by a line that began at the intersection of the coast and border reservations and ran north to 15 leagues from Nacogdoches, thence west to the Navasota River, south in an irregular line along the Navasota and east to the point of beginning.”

Edwards posted notices in Nacogdoches demanding that all landowners show evidence of their claims or forfeit the land. His threatening behavior raised the hackles of these settlers, some of whom held earlier grants from Spain and Mexico. Even though these grants dated back more than 100 years, not all the settlers possessed legal documents to prove ownership.

A questionable election for alcalde, or mayor, of Nacogdoches in December propelled Edward’s son-in-law, Chichester Chaplin, into office. Tensions escalated dramatically.

The tempest raged until authorities in Mexico annulled the 1826 Edwards land grant and ordered Edwards to leave Texas. Lt. Col. Mateo Ahumada, Mexican military commander in Coahuila y Tejas, set out from San Antonio with 20 dragoons and 110 infantrymen to enforce this resolution. Edwards vowed to recruit an army and win independence from Mexico.

Edwards christened his disputed land grant the Republic of Fredonia, based on a concept first articulated in New York by Dr. Samuel Latham Mitchill in 1800.

He had simply added a Latin ending to the word “freedom” to create “Fredonia.” Edwards appropriated the name and designed a flag with two red-and-white parallel bars and inscribed with the words “Independence, Liberty, Justice.” The red-and-white bars represented the Native American and white inhabitants of the region, and Edwards hurriedly sought to finalize a treaty with the nearby Cherokee to strengthen his claim.

Amid the turmoil, Edwards petitioned Stephen F. Austin for aid. Not only did Austin refuse, but also he sent 100 soldiers to support Ahumada. At the same time, Peter Ellis Bean, a Mexican Indian agent, convinced the Cherokee to side with Austin, who wanted no further part of it. “It is my candid opinion,” Austin wrote to Edwards, “that a continuance of the im-prudent course you have commenced will totally ruin you.”

Edwards appointed his brother, Benjamin, to lead the colony, and then he left for the United States to raise support. Benjamin gathered 30 men loyal to the Fredonian cause and rode through a December blizzard to Nacogdoches. There they seized control of the Old Stone Fort and ripped down the flag of Mexico, re-placing it with their own. The residents of Nacogdoches, most loyal to Mexico, moved out when they learned that the Mexican military was en route.

The newly minted republic survived only a few weeks. When Mexican military forces and Austin’s militia arrived on January 31, 1827, the revolutionaries re-treated across the Sabine River. Not a single Cherokee warrior had shown up to join the revolt. Mexican authorities eventually offered amnesty to all who had participated in the revolt except the Edwards brothers.

The Fredonian Rebellion accomplished little, but some historians consider it the true beginning of the Texas Revolution. Citizens of Nacogdoches, inspired by the taste of freedom, welcomed Sam Houston to their city and elected him to the first colonists’ convention in 1833, setting a course for liberty that would be realized in less than a decade.

——————–

Martha Deeringer, a member of Heart of Texas EC, lives near McGregor.