Early travelers along the fabled Camino Real, or the King’s Highway, in what is now Cherokee County in East Texas saw a series of mysterious mounds in a prairie opening in the forests not far from the Neches River. Some of those travelers had probably seen similar earthen structures, sites of former ceremonial and burial grounds, along the Natchez Trace in Mississippi and elsewhere.

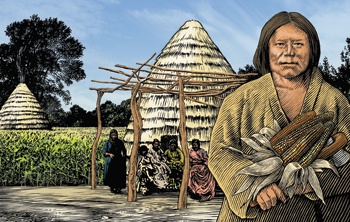

The mounds, now known as the Caddo Mounds State Historic Site, are the most visible reminders of the Caddo people, who flourished all over East and Northeast Texas for hundreds of years, their farms and villages spilling over into modern-day Louisiana, Arkansas and Oklahoma. The Caddo are also credited with giving Texas its name, which has been loosely translated to mean “friendly.”

The Caddo existed for the better part of a millennium on the southern and western fringes of the great Mississippian native cultures. The Texas branches, sometimes referred to as confederacies, settled in the valleys and near the banks and tributaries of the Red, Sabine and Neches rivers. The Texas Caddo consisted of the Kadohadacho along the Red River; the Hasinai in the Neches and Angelina River valleys; and the Natchitoches on the Red River.

The Hasinai called each other “Tayshas,” which meant “friends” or “allies.” The Caddo welcomed Spanish explorers as “Tayshas,” which the Spanish wrote as “Tejas” and we know as Texas. Some of La Salle’s hard-luck sailors are said to have deserted to the Caddo because they were friendlier than their French comrades.

That information might lead some to think of the Caddo as always docile, but that would be wrong. The Caddo were known as fierce warriors, particularly in battles with enemy tribes, as well as farmers, potters and traders. They fought the Apache and Choctaw and were reported to have been every bit the match of the Comanche and other tribes noted by history for their savage torture techniques. The first Europeans to encounter the Caddo, Hernando De Soto’s army in 1541, were attacked. The Europeans left the Caddo alone for the next 150 years or so.

The Caddo set themselves apart from most Texas tribes by becoming accomplished farmers, growing the “three sisters” crops of corns, beans and squash along with watermelons, sunflowers, tobacco and other crops. Ever resourceful, the Caddo planned for dry years by saving and protecting two years’ worth of seed corn “so that, if the first year is dry, they will not lack for seed the second year,” as recounted in C. Allan Jones’ book Texas Roots: Agriculture and Rural Life Before the Civil War.

Archaeologists have determined that the early Caddos chose to settle at the Caddo mounds site about 800 A.D. and stayed until the 14th century, when the mounds were abruptly and mysteriously abandoned.

Some of the artifacts found at the Caddo mounds are trade items from as far away as Illinois and Florida and include shell from the Gulf Coast and copper from the Great Lakes region. Caddo pottery is well constructed and functional and includes plain and finely decorated ceramics.

Though historians believe the Caddo culture was already in decline by the time they were “discovered,” the arrival of Europeans dramatically hastened the demise. Smallpox struck the Caddo in 1690 and became a plague in the 1700s. The Caddo were placed on the Brazos Indian Reservation in 1855, and in 1859 a thousand or so Caddos were removed to the Washita River in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma.

Aside from the mounds, the Caddo left behind a sterling reputation in Texas.

“For hundreds of years the Caddos were the most highly organized and successful people in what is now Texas,” Jones wrote in his book. “The Caddo food system was reliable, sustainable, and its communal nature gave the Caddos and other Mississippian peoples the leisure to develop complex hierarchical societies with impressive material cultures.”

——————–

Clay Coppedge, who lives in Granger, co-authored “The Dukes of Duval County” in the May 2009 issue of Texas Co-op Power.