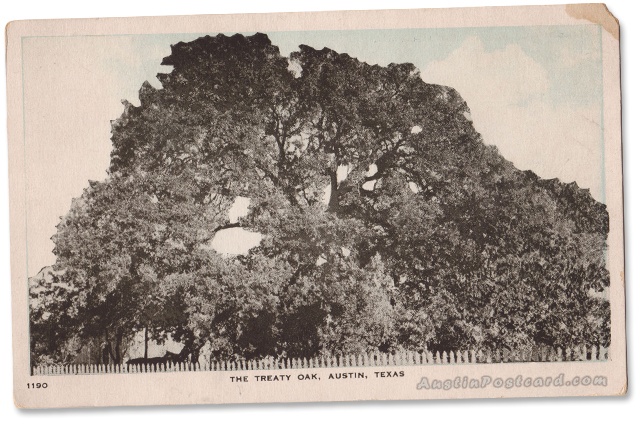

The stately Treaty Oak on Baylor Avenue near downtown Austin has witnessed more than five centuries of Texas history. Deeply rooted in the rich soil of the Colorado River bottom, the ancient, 50-foot-tall live oak is the sole survivor of a group of 14 trees known as the Council Oaks, a grove that shaded the ceremonies of Native Americans long before the city of Austin sprouted in the Texas Hill Country.

Legend has it that Comanche and Tonkawa maidens brewed a magical tea made from wild honey and tender leaves plucked from the Council Oaks, offering it to warriors as protection in battle. A boundary treaty signed by Stephen F. Austin and local native leaders beneath the tree may have given the Treaty Oak its name.

In 1861, when Gov. Sam Houston was removed from office for refusing to sign the oath of allegiance to the Confederate States of America, he climbed aboard a buggy beside his driver, Jeff Hamilton, and said: “We have plenty of time now, since we are both out of office, so turn back and we’ll drive over to see the Treaty Oak.” By some accounts, the great statesman sat in the shade of the oak’s spreading branches, contemplating his fears about Texas’ secession.

The city of Austin grew up around the Council Oaks like broom weeds in June. One by one, the towering trees fell or were cut down until, by probably the 1920s, the Treaty Oak stood alone.

In 1927—with its diameter measuring a mighty 5 feet wide chest high on the trunk, and its canopy stretching almost 130 feet—the Treaty Oak was admitted to the American Forestry Association Hall of Fame for Trees and declared the most perfect specimen of a North American tree.

For the next six decades, the tree spread its dappled shade over picnics, weddings and scores of visitors, but, in the spring of 1989 ominous signs indicated that all was not well. A wide band of dead grass encircled the trunk, and an Austin woman phoned the city forester’s office in June to report seeing brown leaves. Experts discovered symptoms of chemical damage. Forestry officials took soil samples, removed six to eight inches of topsoil from around the tree and injected a fine powder of activated charcoal mixed with water, which binds chemicals to the charcoal mixture’s surface, making them harmless to the tree. Another solution of microbes helped deactivate more of the chemical. Then the lab report came: The tree had been poisoned with Velpar, an herbicide used to kill hardwoods growing among pine trees, which the chemical doesn’t harm.

Investigators believed that some or all of a gallon of the toxic herbicide—roughly 25 times the amount required to kill the tree—had been poured in a circle near the tree in a deliberate act of vandalism. Velpar’s maker, DuPont, offered a $10,000 reward to find the perpetrator. In late June, the Austin Police Department arrested Paul Stedman Cullen, a feed-store worker with a checkered criminal past who was accused of trying to kill the tree as part of an occult ritual. Cullen was convicted of felony criminal mischief and, because of a prior felony conviction, was sentenced to prison. He served three years of a nine-year sentence and died in 2001.

As the tree continued its frightening decline, Austin City Forester John Giedraitis called in the cavalry. A group of experts from around the country gathered for a single day to tackle the problem. Texan billionaire H. Ross Perot gave a blank check to pick up the tab. To reduce stress on the tree, it was cooled during the heat of the day with water mist and sun-blocking screens. Fertilizer was applied to its aerated roots, and soil was removed and replaced to a depth of 3 feet. The valiant oak produced one flush of leaves after another in a desperate attempt to rid itself of the poison, slowly slipping into critical condition. “Thousands of people from all over the country visited the Treaty Oak, leaving get-well cards, candles and letters at its base,” says Giedraitis, now urban forestry program manager for the Texas Forest Service. For many, the tree became a symbol of old-fashioned quiet strength pitted against the evil that seemed to be invading the modern world.

Today, about half of Treaty Oak’s crown remains. Giedraitis took a pencil-sized graft, or cutting, from the tree and planted it near its injured sister, where it’s thriving. As for the big tree, “The lost crown is growing back,” says Giedraitis, “and the tree began producing acorns again a few years ago.”

The Treaty Oak joins a long list of Texas heroes who waged desperate battles for survival in the Lone Star State.

——————–

Martha Deeringer, frequent contributor