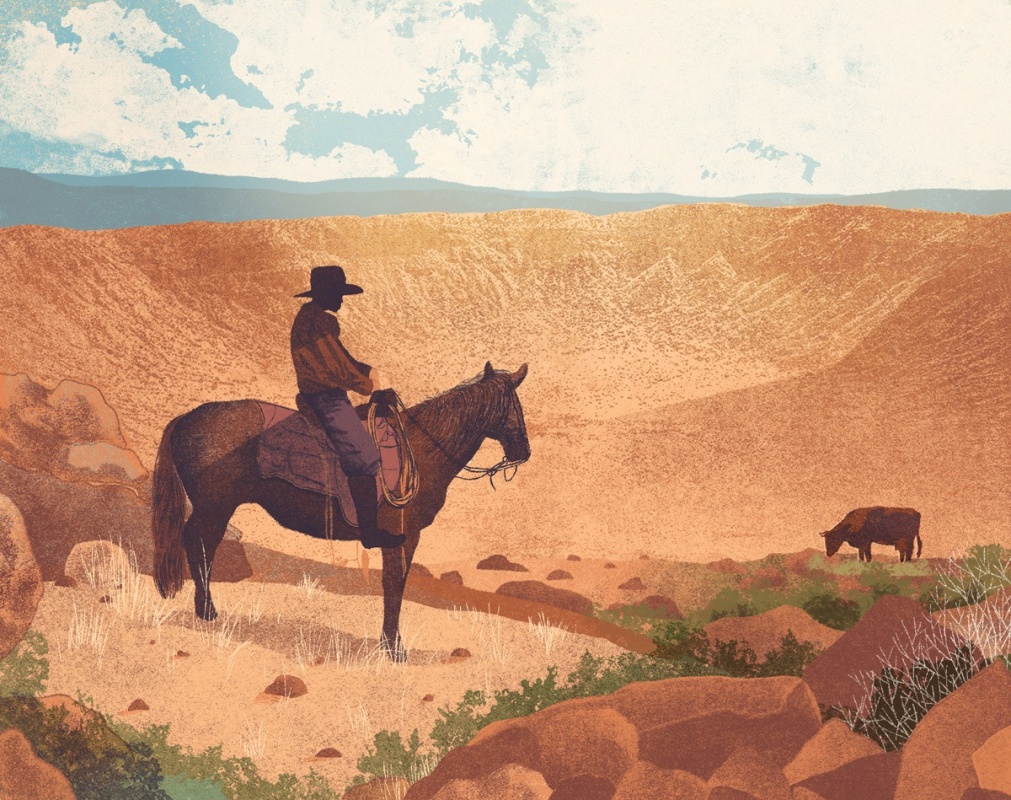

The story behind the discovery of the Odessa Meteor Crater begins more like a Lonesome Dove epilogue than like a scientific endeavor.

A 12-year-old boy gets credit for first reporting this disruption in the undulating Chihuahuan Desert terrain southwest of Odessa. In 1892, Julius D. Henderson, son of Ector County rancher John J. Henderson, rode his horse out in search of a lost calf. He located the wandering bovine grazing in an odd, oblong-shaped dropoff in the landscape, and after returning home, he told others about the strange hollow.

In 1920, Elisha Virgil Graham—whose family had settled in the area only because their wagon oxen had accidentally been killed by a freight train on the Texas and Pacific railroad tracks between Monahans and Odessa—discovered a peculiar, lava-like rock near the center of the sunken area. Graham gave the rock to his friend, Samuel R. McKinney, the first mayor of Odessa. McKinney fancied the strange rock and used it as a paperweight in his office.

Finally, in 1922, a scientist took notice, but this was also rather by accident. A.C. Bibbins, a Baltimore geologist visiting the mayor’s office on business, noticed the peculiar rock and examined it more closely. Bibbins declared that the paperweight was actually a meteorite, and McKinney permitted him to dislodge a shard and send it to George P. Merrill, the head curator of the Department of Geology at the United States National Museum (now the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution), for analysis. Merrill confirmed Bibbins’ conclusion: The paperweight was a meteorite composed of extremely hard nickel-iron.

Scientists immediately began flocking to Odessa to examine the crater and the land surrounding it because the site was a fertile meteorite hunting ground. They initially theorized that the Odessa meteorite was little brother to the Barringer meteorite, which created a much larger crater in Arizona 50,000 years ago. There were some similarities between the craters, and scientists suggested that the Odessa meteorite had broken away from the Barringer before impact. The Barringer Meteorite Crater was the first officially designated meteorite crater on Earth; the Odessa Crater became the second.

Over the next few decades, researchers would repeatedly drill into the big crater in Texas, attempting to locate the main meteorite mass. On October 24, 1965, the Odessa Meteor Crater was designated a National Natural Landmark, and in the spring of 2002, a museum was completed at the site, providing information on meteorites and actually selling pieces of the Odessa meteorite.

In May 2003, Vance Holliday of the University of Arizona drilled into the crater again, this time for core samples to determine the crater’s age and the effects of the meteorite impact. From the core samples, Holliday dated the crater at about 63,500 years old, demonstrating that the Odessa and Barringer events were unrelated. The results also suggested that the main meteorite impact initiated catastrophic damage farther than a mile in every direction from the event’s epicenter, producing 621-mph winds and a thermal pulse. This means that any woolly mammoths, giant ground sloths or saber-toothed tigers wandering through the impact pulse radius at the time might as well have been subjected to a nuclear detonation.

Holliday’s contributions were followed by impact simulation studies by David Littlefield, formerly of the University of Texas and now a mechanical engineering professor at the University of Alabama-Birmingham. Entering earlier geologic data and impact analyses into databases at the Texas Advanced Computing Center in Austin, Littlefield created a 3-D virtual recreation of the Odessa impact. The simulation calculations indicated the Odessa meteorite was much larger than previously thought and wound up intersecting with the Earth more like a glancing blow than a direct hit.

“It’s rare for a meteor to strike the earth at such a shallow angle,” Littlefield says. “Most meteor strikes tend to produce crater diameters that are roughly equivalent to the crater depths. The depth-to- diameter ratio of the Odessa meteor crater was off. It’s got a much larger diameter relative to the depth.”

The advanced computer simulations explained why.

The meteorite that hit near Odessa was oblong and struck the earth at a low trajectory with its flat side, traveling at a speed of 57,600 miles per hour. “Most of the meteor vaporized on impact,” Littlefield says, “but if it had been larger, it might have ricocheted back into space.”

A failed celestial skipping stone in West Texas! Does Larry McMurtry write sci-fi?

——————–

E.R. Bills is a writer from Aledo.