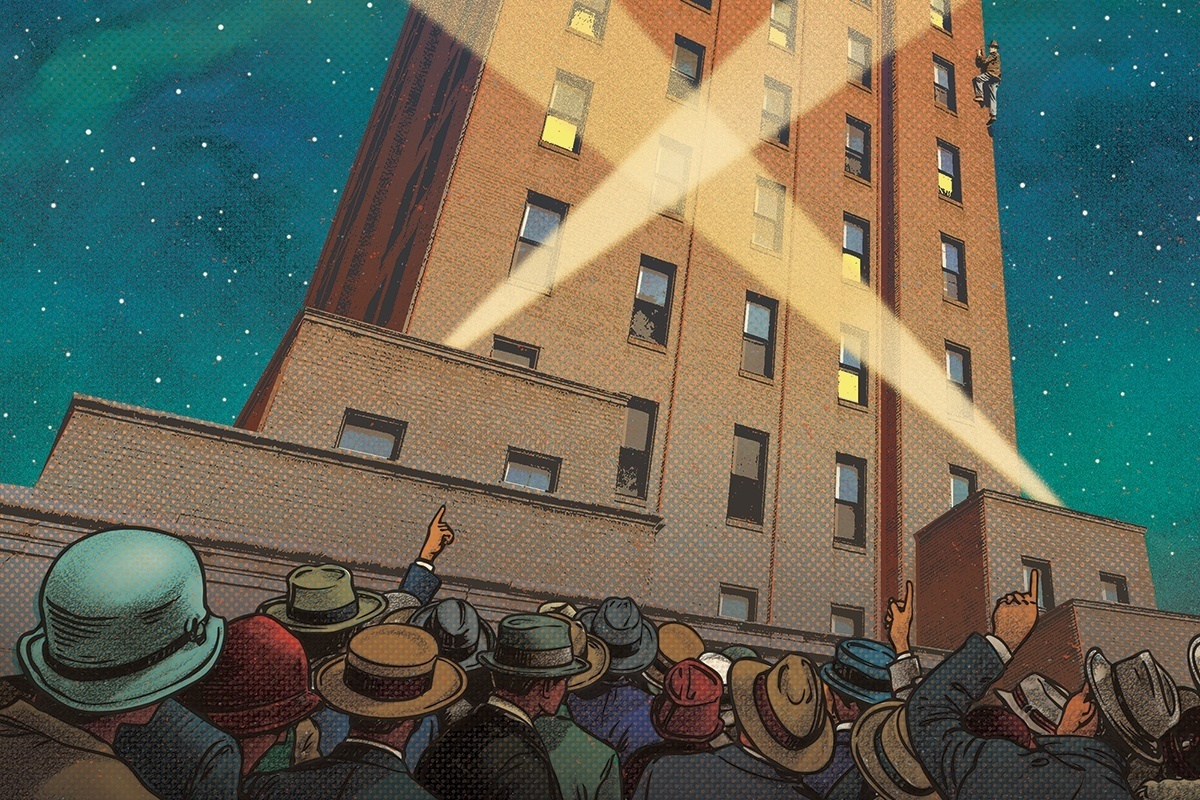

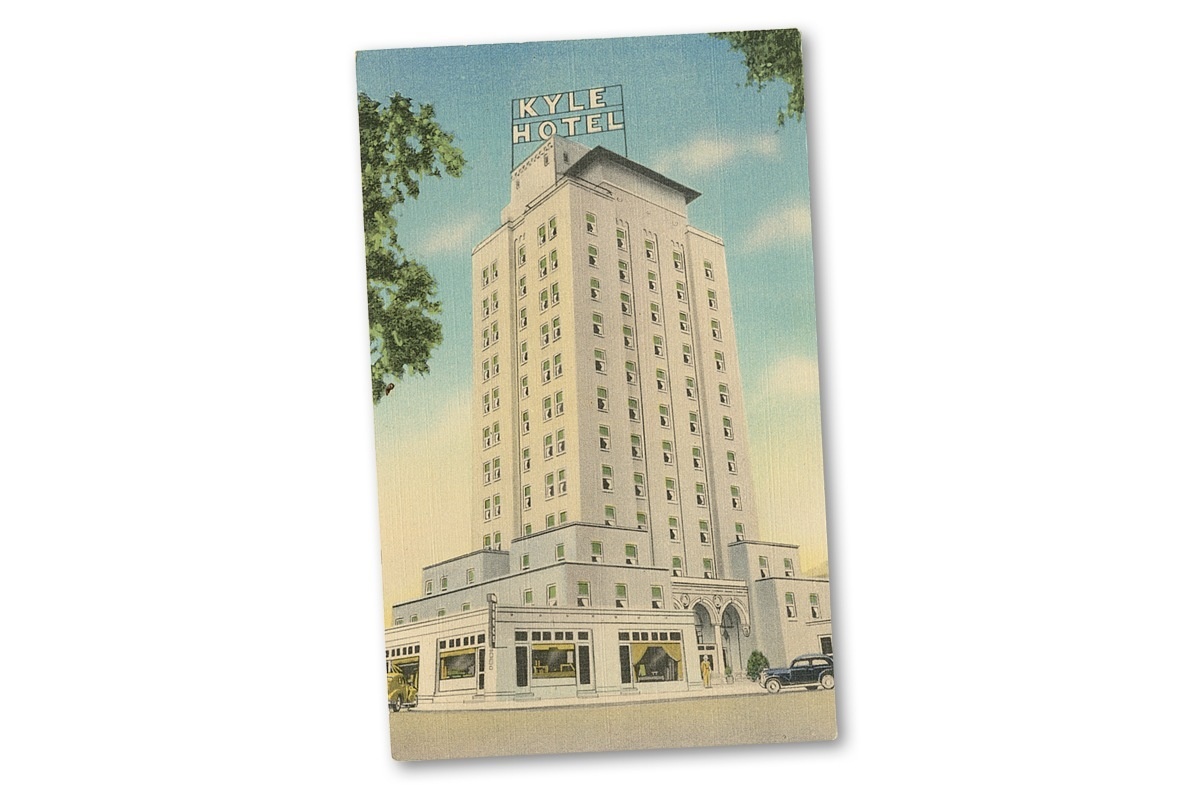

On January 21, 1929, the “human fly” gripped the brick wall and slowly ascended Temple’s sleekly narrow Kyle Hotel. A crowd of observers, decked out in their Sunday best, exchanged knowing glances and looked skyward. Halfway to the 13th and final floor, the man-fly pulled a Coca-Cola bottle from his pocket and took a leisurely sip. The onlookers laughed and cheered. Those lucky enough to purchase tickets to the grand opening party ventured inside to dance to Henry Lange and his orchestra’s hit song, Hot Lips. For $1.50, they could stay the night in one of 125 rooms appointed with steam heat, ceiling fans and running ice water.

In October of that year, the stock market crashed, foretelling the Great Depression. Farmers saw cotton prices plummet. The town’s major employer, the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway, implemented layoffs and pay cuts. Four of Temple’s five banks closed. Temple’s population remained static at 15,000 throughout the 1930s. Yet the Kyle and other high-rise Texas hotels like it held on for decades as towering symbols of something larger. Soldiers huddled in them during World War II. Community groups met for lunch. High school kids held proms.

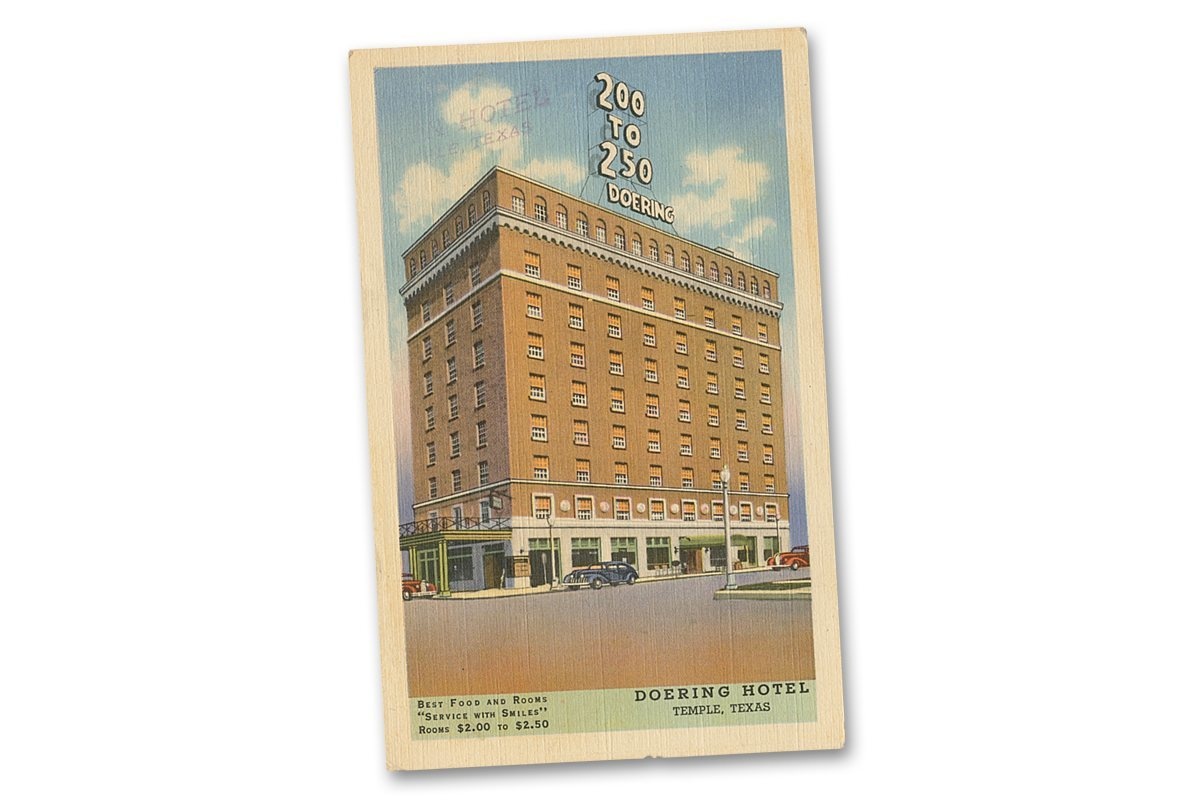

The Kyle was the third “skyscraper” in Temple. The 113-room Doering Hotel—later sold and renamed the Hawn Hotel—had celebrated its opening in 1928 with a different human fly ascending its nine levels. The six-story Professional Building came second and housed a grocery, stenography school, barbershop, law office, flower shop and cigar store.

New Yorkers might argue whether any building with fewer than 20 stories, or perhaps even 50, could be billed as a skyscraper, but architect T.J. Gottesdiener, quoted in the Christian Science Monitor decades after the firm he worked for designed Chicago’s iconic Sears Tower, perhaps put it best: “What is a skyscraper? It is anything that makes you stop, stand, crane your neck back and look up.” In the late 1920s, high-rise buildings began to ascend in Texas, and they became a symbol of good times, progress and optimism in tough times ahead.

Frank Doering was a prominent Temple resident who sold his Ford dealership to jump into the hotel game. Doering’s family occupied the eighth floor, just below a ballroom that became a vital part of the Temple social scene. His grandson, Frank Harlan, now 85, spent a chunk of his childhood in the hotel, getting haircuts in Shorty Carmen’s barbershop, picking out his own steaks in the kitchen, and pushing the buttons to go up and down in the elevator repeatedly while its operator sternly looked on.

“I remember listening to the trains from the hotel,” Harlan said. “They still had steam engines back then. You would hear them blow the whistle and the sound of the wheels as they hit the crossing.”

Well-made, reliable elevators were one of the keys to the rapid construction of high rises, as were the mass production of steel and a better understanding of structural loads. In Texas, health and transportation also factored into their construction. Temple was founded by the railroad in the 1880s, and residents quickly had a need for quality medical care, which led to the construction of what is now Scott & White Memorial Hospital. Hospital co-founder Dr. A.C. Scott Sr. worked with Beaumont businessman W.W. Kyle to open a hotel that could house hospital visitors. The hotel found success under the management of Theodore Brasher “T.B.” Baker’s hotel chain that included the Menger and Gunter hotels in San Antonio, the Stephen F. Austin in Austin, the Baker in Dallas and the Galvez in Galveston.

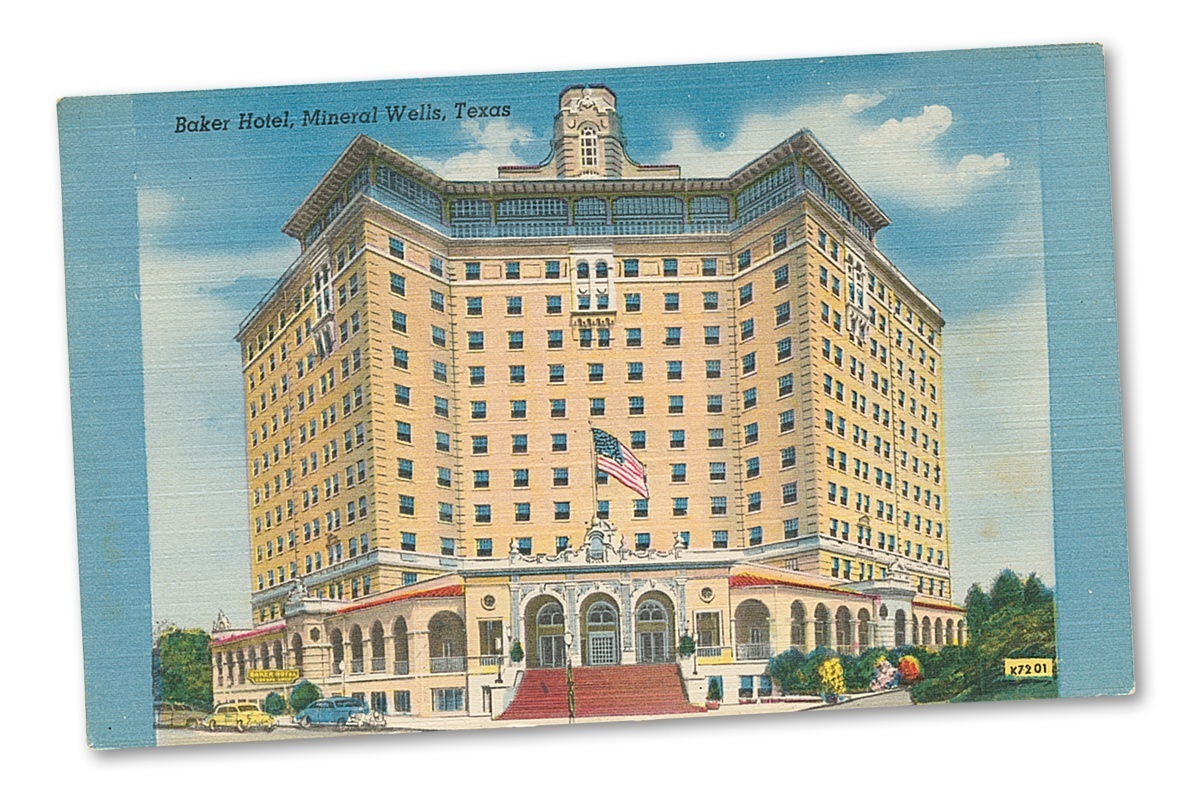

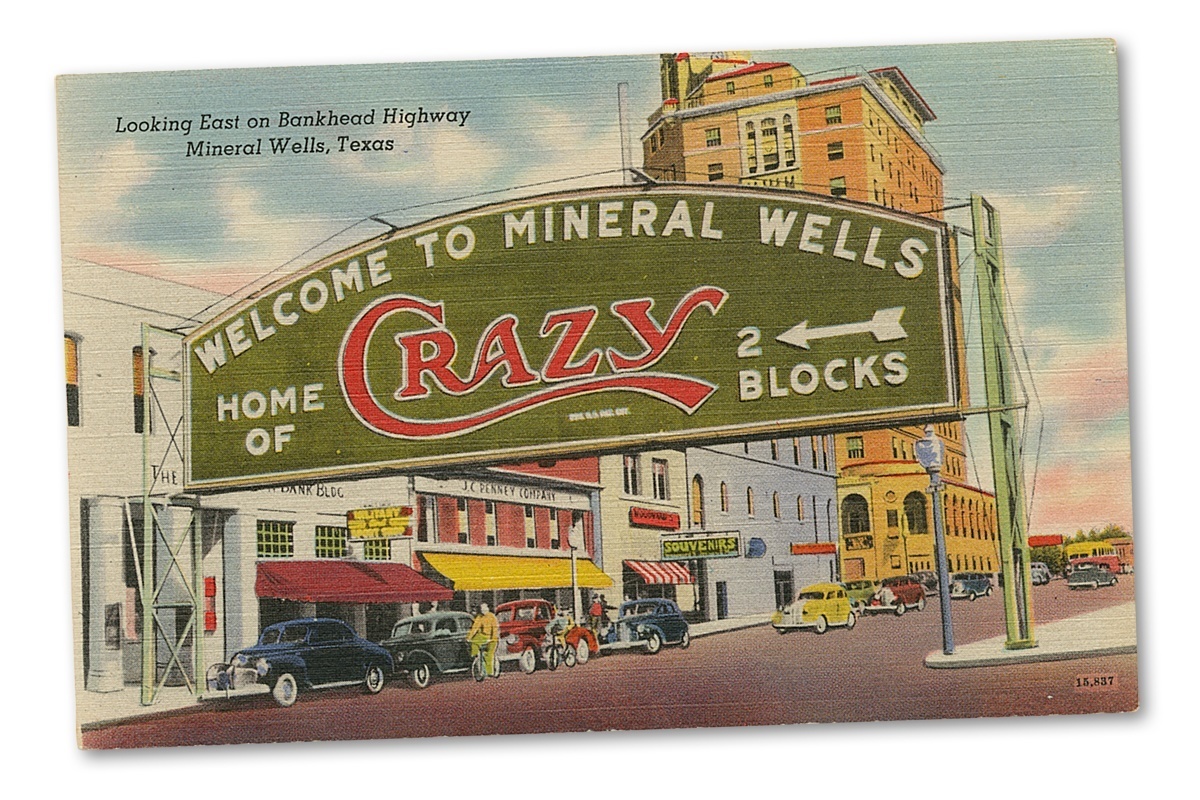

But the hotel magnate’s name is most closely associated with the Baker Hotel in Mineral Wells, a 14-story edifice visible for miles. Since the 1880s, Mineral Wells, 50 miles west of Fort Worth, has staked its name and reputation on mineral water, and by 1910, 150,000 visitors a year came to “take the waters” to cure what ailed them. In 1927, locals raised $150,000 to build the hotel.

Hotel impresario Baker saw the potential, and the 450-room Baker Hotel opened just weeks after the stock market crash in 1929. The hotel was a trifold marvel with an Olympic-size outdoor pool, a bowling alley, an 18,500-square-foot drinking pavilion and the rooftop Cloud Club that attracted celebrities including Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Jean Harlow and even the Three Stooges. During World War II, the hotel was filled to the brim with soldiers.

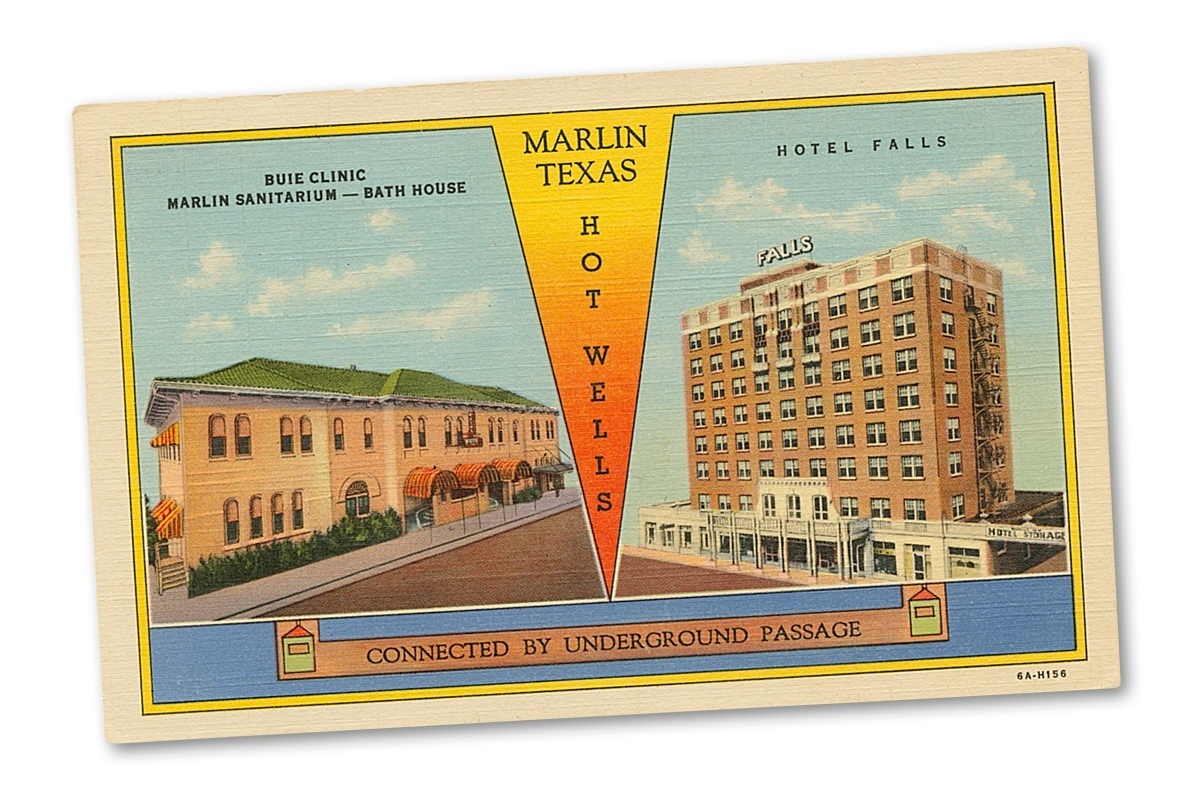

A similar lure of healing waters in the Central Texas town of Marlin led Conrad Hilton to open his eighth Hilton Hotel there in 1929. The nine-story structure, later renamed the Falls Hotel, connected through an underground tunnel to the Marlin Sanitarium-Bath House, opened by Dr. Neil Buie across the street. As many as 100,000 people a year came to Marlin via three rail lines.

New York Giants Manager John McGraw was so convinced of the mineral water’s curative powers that he moved the baseball team’s spring training to Marlin between 1908 and 1918, a stretch in which the Giants won the National League pennant four times. In her book, Taking the Waters in Texas (University of Texas Press, 2000), Janet Mace Valenza writes that the Marlin regimen involved drinking mineral water followed by two hours of baths, including full-body rubdowns with salt and oil.

Time passed and trends changed. Mineral baths were replaced by antibiotics and other medicines. Interstate 35 sent traffic zooming past Temple, and downtowns fell out of vogue. The 1970s saw the decline and then eventual closing of these hotels. The Falls and Baker became the targets of ghost hunters. Many attempts have been made to reopen them. Sometimes a reimagining worked. The mineral water still flows continuously from a fountain across from the Falls Hotel, but only a barbershop remains inside the hotel’s doors.

But in Mineral Wells, the big story has been a nine-year effort to revitalize the Baker. A team has been working to attract foreign investors to cover an expected $56 million price tag. Among the partners is Dallas businessman Brint Ryan, who did the impossible in 2012—he reopened the beautifully revived Hotel Settles in his hometown of Big Spring, as if turning the key on a portal to the past.

In Temple, the city obtained a Department of Housing and Urban Development grant in the late 1980s to transform the Kyle Hotel into low-cost housing for the elderly, and it remains open under the direction of the city’s housing authority. The Doering/Hawn Hotel was purchased by the city of Temple with the intent to find a developer and bring it back to life. A deal is in the works, but, as with the Baker, full financing is pending.

Harlan, the grandson of its founder, dreams of living long enough to move into the renovated building. He toured the hotel’s stripped-down ground floor last year. Age kept him from climbing the narrow staircase to the top, but a newspaper photo of the old hotel jarred him. In it was a ballroom piano wizened by time and covered with pigeon droppings. “I took piano when I was younger, and I remember doing a recital at the hotel. I was maybe 12, and I played American Patrol [a tune made popular by Glenn Miller] in the ballroom. It was probably on that very piano.”

——————–

Joe O’Connell is an Austin writer.