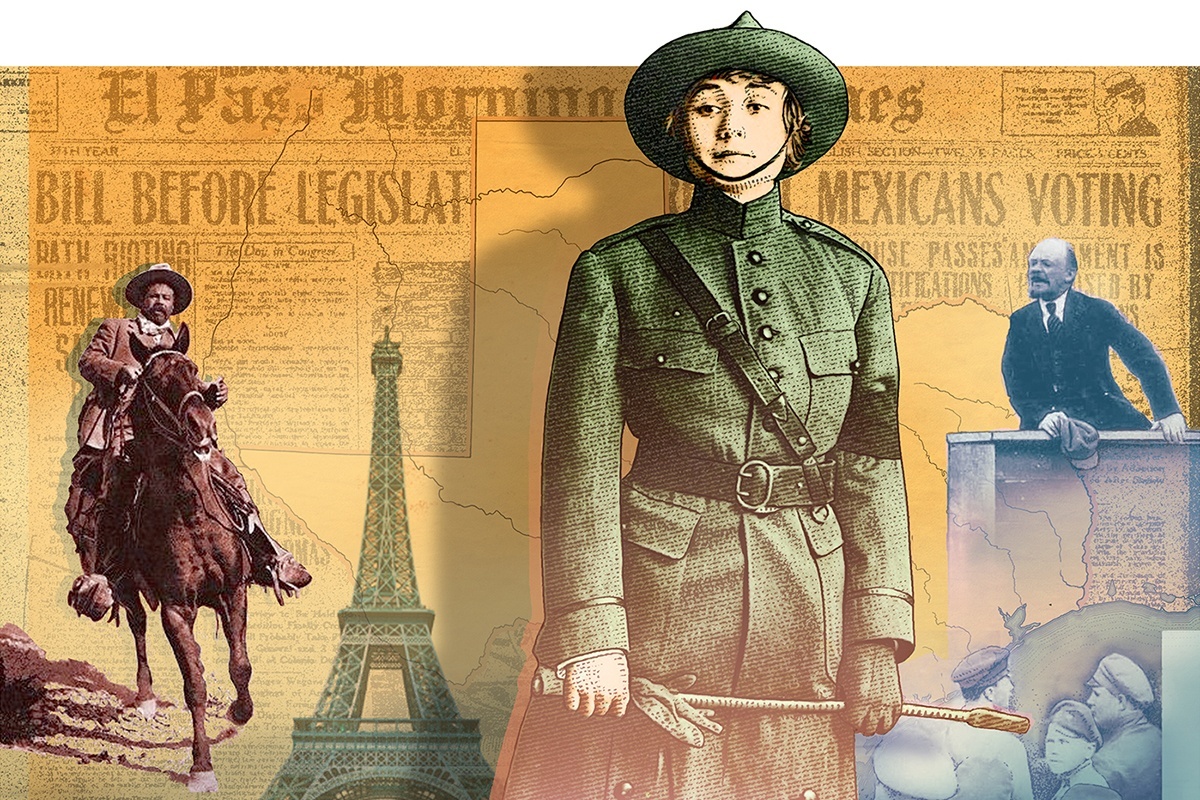

In 1916, 25-year-old reporter Peggy Hull blew into El Paso to cover the U.S. military response to Pancho Villa’s attacks for the Cleveland Plain Dealer. Eager to be taken seriously by her editors, Hull crafted her own uniform of khaki pants, knee-high boots and a brown hat, modeled after the Ohio National Guard soldiers whom she followed to Texas to cover the border conflict.

While embedded with the soldiers, Hull wrote compelling stories, and El Paso newsmen soon took notice. The El Paso Herald described how the young but seasoned reporter had fought a “real battle” with her editors at the Plain Dealer.

Hull pushed to work with the Ohio troops, but her editors refused to send a woman to the conflict. In response, she funded her own way to Texas in the first of several daring moves that propelled her to become first documented American female war correspondent.

Hull started in the news business in her home state of Kansas after an editor offered her a typesetting job—if she didn’t mind ruining her nails. When a major fire broke out and there was no one else available to cover the story, Hull took the assignment and advanced to the rank of reporter.

Once a reporter, Hull moved from one newspaper to the next, giving her notice as soon as she hit the limits of what papers would allow from a female reporter. In almost 10 years, she jumped through six states, and when the Plain Dealer editor resisted her request to cover the hunt for Villa, Hull stayed in Texas.

“Won’t come back; fire me if you like,” she wired to him. He immediately fired her.

Hull’s reporting from the border was so powerful that within a few months, she was reporting for the El Paso Morning Times. The next spring, the United States entered World War I, and reporters lined up for their foreign correspondent credentials.

Hull wanted her own press pass because she knew she wouldn’t gain front-line access without it. The War Department denied her, but Hull’s El Paso editors allowed her to push forward.

Without a press pass, traveling to France proved to be another challenge. Her male counterparts received visas to England and France, but Hull was denied and had to appear before a judge for approval.

Once in Europe, Hull reported from the sidelines, a hindrance she transformed into an advantage. She met a general who allowed her to interview soldiers at an artillery training camp. While the credentialed reporters waited to report on military action, Hull sewed buttons onto the shirts of soldiers waiting to fight. As she worked, they told her their life stories, which she reported to Texas readers.

Her editors in El Paso put her stories on the wire, and Hull’s coverage went national. Several papers even claimed her as one of their own. The other correspondents in Europe quickly became jealous and demanded that the military ban her from interviewing soldiers.

This proved an insurmountable hurdle, but before Hull packed her bags to return to Texas, the Morning Times published an article in which she chided the newsmen who pushed her out. She let them know she wasn’t defeated: “I learned to be a good loser long before I came to France,” she wrote.

Back in Texas, Hull resumed reporting El Paso news, but a year later, she set her sights on a new foreign conflict—the Russian Civil War. Hull was desperate to head to the Siberian city of Vladivostok. It didn’t interest her El Paso editors, but Hull found another sponsor, the News-paper Enterprise Association.

Hull found her way onto the War Department’s list of approved reporters. In doing so, she became the first American female war correspondent.

During World War II, Hull was one of 127 women who received foreign correspondent credentials from the War Department. Some of the women headed to Europe and others set out for the South Pacific. Both groups traveled a path first paved by Peggy Hull.

——————–

Emilie Le Beau Lucchesi is the author of Ugly Prey: An Innocent Woman and the Death Sentence that Scandalized Jazz Age Chicago.