Spend enough time in the fields where thousands of young onion plants are being harvested, and you, like Bill Martin, will crave a juicy hamburger topped with fried onions.

Such cravings are a daily work hazard for Martin and his brother-in-law Bruce Frasier, who belong to the fourth generation of an onion-raising family in Carrizo Springs. Their Dixondale Farms lays claim to being the oldest and the largest grower of onion plants in the United States, shipping more than 420 million pungent plants a year.

The Dixondale crew stopped raising eating-size onions in 1965. Instead, it plants onion seeds and harvests small plants to be shipped to other growers. And they can chow down on their onions bought at the local grocer or across the country.

Martin, vice president of Dixondale Farms, keeps a bushel of onion lore under his smudged white Stetson. For example, onions are daylight-sensitive rather than temperature-sensitive, he explains. The onions that thrive in the northern states’ 16 hours of summer light will never develop much of a bulb in Texas’ shorter summer days. The North’s longer days produce hotter onions. Texas, by contrast, is known for its 1015 SuperSweet onions, which are to be planted in the Rio Grande Valley on October 15 for April harvest. Dozens of varieties for various climates get their start at Dixondale Farms.

“People in Georgia [known for its sweet onions] don’t want it known, but a lot of Vidalia onions start life here in Dimmit County, Texas,” Martin says. The farm ships Bermuda onion plants to Bermuda, too.

Dixondale Farms staggers its plantings from late August through January on 350 to 400 acres laid out in a narrow three-mile strip for easier harvesting access. During one week in October, crews planted 28 varieties of onion and leek seeds in double rows—about 60 million seeds. Before the seed goes in the ground, the growers know where 80 percent of the plants are headed: mail-order customers, farm and garden stores, and retailers such as Lowe’s, Wal-Mart and The Home Depot.

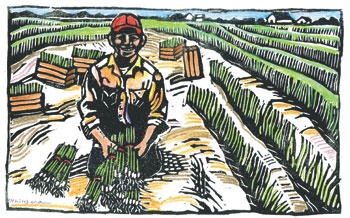

In October, harvesting of the slender, tender plants begins, with onions going to supply growers and gardeners in the Rio Grande Valley and Florida. Cutting and bunching is still done by hand. Earning up to $800 per week, the field hands kneel in the cultivated soil, unearth the plants, bind 60 plants together with fat rubber bands and trim the tops off, leaving behind what looks like the entire world’s supply of chives. A bunch of tiny, green-topped bulbs fits in a circle made by your thumb and index finger.

“When it gets hot in the afternoon, cutting the tops off makes your eyes water,” Martin says. At this size, it’s impossible to tell varieties apart, so careful record-keeping is essential.

“You control growth in onion plants by when you water,” Martin explains. Dixondale relies on its 1,000-foot-deep wells, drawing on a water table that is much higher now than it was 50 years ago. That’s because the region’s farmland has transitioned to hunting leases. Because onions wear out the soil, Dixondale Farms rotates cantaloupes, onions and leeks over the farm’s 2,200 acres.

Martin says all the best-tasting dishes have onions in them. That’s why, besides overseeing onion harvests and the family cattle ranching operation and giving visitors tours, he likes to contribute onion recipes to the Onion Patch, Dixondale Farms’ quarterly newsletter.

Joseph McClendon, the great-grandfather of Martin and his sister Jeanie Martin Frasier, founded Dixondale Farms in 1913. While their father, Wallace Martin, still knows his onions, Jeanie’s husband, Frasier, known as the Onionman, is president of Dixondale Farms. When Frasier came into the business run by his father-in-law in the 1980s, he shifted the business to mail-order selling. The U.S. Postal Service custom-designed a shipping box with air ventilation holes to keep the onion plants fresher, and the farm mails tractor-trailer loads of boxes at a time.

The packing crew fills orders for the popular sampler of red, yellow and white onions based on the length of day at the destination. Trucks line up to haul drop shipments of plants for backyard gardeners and a dozen mail-order nurseries in the eastern United States. People with roadside stands often order 30 bunches of assorted plants.

“The people up north, snowed in, are among the first to order,” Martin says.

“A lot of customers pick up the phone and want to visit with us to brag about their onion crop,” Frasier says. “We’re trying to educate. If the same question comes up, we address it in the newsletter.”

Photos of grinning customers proudly displaying their prize onions fill the catalog, newsletter and website. “I don’t know what our future will be. None of the fifth generation has yet committed to coming back,” Frasier says. But given Dixondale Farms’ tradition of having a son-in-law lead the company, the family has no reason to cry about the onion business.

——————–

Dixondale Farms: P.O. Box 129, Department WP08, Carrizo Springs, TX 78834-6129; for more information, call 1-877-367-1015 or go to www.dixondalefarms.com.

Harlingen writer Eileen Mattei is a Nueces Electric Co-op retail member.