A helicopter touches down in an open field. Ken Graff hunches over and approaches it at a trot. He’s met with a smile of exhilaration and relief from a teenage boy in the passenger seat who pops out and is quickly replaced with another. Ken shouts something to the pilot over the whut-tut-tut of the rotors. They are both grinning and nodding. Ken holds his straw cowboy hat against the wind of the sweeping blades as he turns and shuffles back to the sign-up table under an oak tree where a short line of mostly young people have bought their tickets and await their turn for a ride over an amazing sight: a giant maze carved from a cane field.

This is not the kind of scene one would expect at a farm, but it’s not uncommon here at the Graff Family Farm in Hondo from late September through late November. It is then that this small corner of the Graffs’ land along U.S. Highway 90, about 40 miles west of San Antonio, is transformed into the South Texas MAiZE.

Now in its ninth year, the South Texas MAiZE—an “agri-tainment adventure” promising “farmtastic” fun—has become an effective, if atypical, solution for the Graffs to maintain their family farm. The main attraction is, of course, a giant maze—cut from 7 acres of sorghum Sudan grass known as haygrazer that’s grown to feed cattle. “It looks a lot like corn but is much more drought resistant,” Ken explains. Kids and adults alike enjoy the challenge of making their way through the giant labyrinth. On average, a walk through the maze takes one hour from start to finish.

The last of a few nontraditional ideas for turning a profit on the farm, the maze is the idea that stuck, and took root, growing bigger every year. By the fifth year, 2006, proceeds from the event had helped the Graffs pay off all previous debt amassed from a string of unrelenting droughts. Today, while the Graffs still dabble in typical agricultural practices—they maintain a small herd of cattle and run cattle for other ranchers—the maze accounts for the vast majority of their income and has, at last, made their farm self-sustaining.

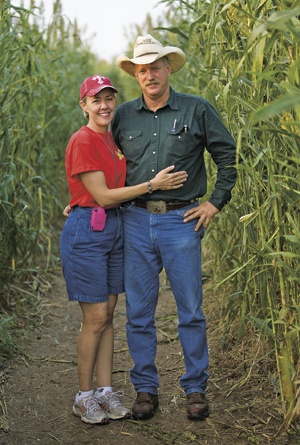

Ken and his wife, Laurie, sit at a picnic table in the shade of an ancient oak between a giant rubber pillow-shaped trampoline called The Corn Popper and some food booths. They talk about the challenges faced by family farms today and the changes that have occurred in the space of just a generation. They describe how Ken’s parents ranched and farmed this same land for more than 30 years, raising cattle and growing wheat, oats and milo to support a family of four.

“They didn’t have to think about change,” Laurie says. “We were forced to.”

Ken’s face darkens as he recounts the devastating droughts that recently have plagued Central Texas. The years “2008 and 2009 were the worst we’ve seen here,” he says. “It even beat the drought of the ’50s. There is no way we would have survived it if we weren’t doing this.” Last fall, Medina Lake was about 48 feet below normal.

Ranching and farming has been a way of life here for the Graff family ever since Ken’s great-great-grandfather, Louis Graff, who emigrated from Alsace-Lorraine in France in 1847 and helped found nearby Castroville, purchased this tract in 1872. With the help of his son Charles, Ken’s great-grandfather, and Adolph, one of Charles’ sons and Ken’s grandfather, the farm and ranch once boasted 10,000 acres. Today, Ken retains just 700 of those. But holding onto that land has—until recently—been anything but certain.

By the time Ken returned from college and started working alongside his father, Ralph, in 1987, the idea of supporting a family entirely on income from traditional farming was already a fading dream.

“When interest rates (affecting operations) hit 20 percent and higher in the ’80s, it just killed everyone here,” the 45-year-old Ken recalls.

To supplement his income from the farm, Ken turned to welding—a skill he picked up in high school. He jokes that welding helped support his “farming habit.” When single, the additional income was “play money,” but once he was supporting a family of his own, the outside revenue was needed just to get by.

When Ken’s father passed away in 1995, the farm was in crisis. Debt had piled up, and Ken and Laurie were searching for a way to make the farm profitable again. A natural beef program supported by the Texas Department of Agriculture offered a possible solution. It promised a higher dollar per yield for chemical-free and grass-fed cattle than raising them by conventional methods. And it could be sustainable at the Graffs’ scale of farming. The Graffs were soon running 250 head of cattle with hopes of a bright future.

But within a year, a bitter drought struck the region. Pastures were reduced to dust.

“I had to burn prickly pear in the dead of summer,” Ken recalls. In extreme droughts here, the cactus is the only plant that survives, and knowing that hungry cattle are going to eat the cactus, ranchers burn the spines off with a blowtorch. Feed had to be trucked in, at considerable cost, and again the debt piled up. “I vowed never to feed through a drought again,” Ken says.

Though their income from ranching improved with better weather in the following years, the Graffs still sought another solution. A chance contact with a member of the San Antonio Chamber of Commerce in 1997 resulted in the idea of starting agritourism on the farm. Within a year, a pavilion was built, and Ken and family were hosting tour and conference groups, bused in from San Antonio, for Texas-style barbecues and Western entertainment. A growing number of groups arrived each year, bringing a considerable contribution to the Graff farm’s income.

“Then September 11th happened,” Ken explains, remembering the terrorist attacks of 2001. “When the economy went bad, we went from 20 to 40 tours a year to none.”

Laurie describes having learned about the MAiZE concept from a brochure a customer brought her. As the story goes, Brett Herbst, a Brigham Young University agribusiness graduate, started the first MAiZE in Utah in 1996. Experiencing wild success, he soon found himself consulting with farmers who hoped to replicate the idea. Today, the company helps consult with and support more than 220 MAiZE sites in the United States and abroad, including 10 in Texas.

“Each diversification was an answer to prayer,” says Laurie, having recounted the Graff family’s many ventures over the past years. “We did a little bit of everything. This is finally sustaining us.”

“I haven’t pushed a welding rod in five years,” Ken adds with a smile.

——————–

Jody Horton is a freelance writer and photographer and a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power.