Laurie Greenwell of Austin delivered this eulogy at her mother’s funeral in 2014 in Wimberley:

I was with Mom when she got her diagnosis. The doctor didn’t hold out much hope, given Mom’s age and other factors. As Mom and I walked to the car, my head was spinning, and I wondered if I would even be able to drive home, even as Mom said in measured tones, “Well, I’m really lucky. I’ll be able to get my affairs in order, say goodbye to everyone, and I’m so glad I’m not having a stroke!” Then she continued, “My body has always been so good to me, it will see me through. This cancer will be my chariot out of here.”

And so things came to pass as Mom said.

She did get her affairs in order. She did say goodbye to everyone. But so much more also came to pass: We were blessed with the opportunity to witness someone go into death fully alive.

I have always thought Mom had a sense of the mystic about her. From an early age, she had a quiet confidence that God was all around and that God loved us more than we could ever comprehend. I can’t say I have ever truly known what Mom described, but I have been able to believe because I trusted her confidence. I have felt the same way when reading the words of St. Francis, Yogananda or Julian of Norwich. Some invisible, numinous vibration resonates deep within me.

People have asked me, “What was it like to grow up with a such a wise mother?” Truth be told, Mom didn’t always act like a paragon of virtue. Life with her was not always a cakewalk. She was often frustrated, and her nature was fiery. Once she told me that some days she was so exhausted raising the seven of us that the only way she could get out of bed was to get angry. If my sister, Anne, and I woke up to the sound of Mom vacuuming, we knew we’d be better off spending the day at a friend’s house.

And regrettably, her Kirby vacuum cleaner never broke down. Her marriage, her children and the church didn’t always measure up to her lofty expectations. There were times, even as an adult, when I was afraid of her. Her moods trumped everything in our home. We knew that “if Momma ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy.”

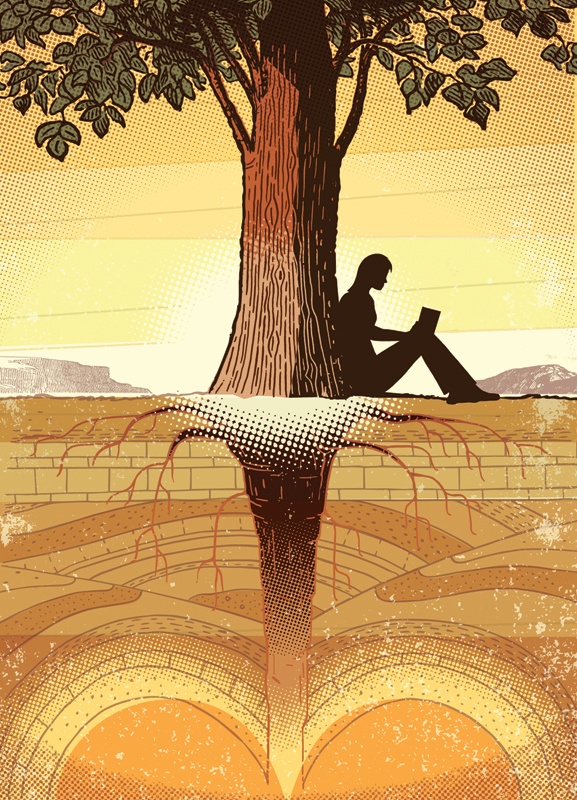

But Mom endeavored to truly know herself. Mom was always, always seeking. I have often thought of her as a great tree with beautiful branches and a network of roots, with a great taproot winding deeper and deeper into the earth, searching for an underground spring to sustain the tree above. As her taproot searched deeper, the more she blossomed. In her book “Bewitchment and Beyond” (available at amazon.com or from a box in her closet), she wrote:

“Consciousness, not belief systems, will prevail against darkness. In physics, it is axiomatic that when the microcosm changes, so does the macrocosm. The universe responds to the growth of consciousness in a single, individual soul.”

She wrote these words, but she also tried to live them. There were difficult years following Dad’s stroke. Mom’s commitment to caring for Dad at home was fraught with challenges. One particularly difficult day, she told me that she took comfort in rising to the occasion. “And,” she said pointedly, “YOU remember that.” (And, yes, I was crying over something.)

After Dad’s death, she struggled to fill the newly empty days. She started taking qigong and tai chi, made new friends, wrote poetry and read with fervor. Aging never signaled stagnation for her. In fact, the opposite seemed to be true. I grew much closer to Mom, me in middle age and her in old age. Mom’s psychological and spiritual growth during her later years was exceptional. She gained almost mythical status among my friends and clients because I couldn’t wait to share what I was learning from her. But the greatest lesson of all was granted during these last, precious months: Mom showed us how to die.

The day after her grim diagnosis, we sat down for breakfast. Because the cancer was at the base of her esophagus, she was having difficulty swallowing. The prognosis was that she would soon not be able to swallow food at all. And thus she said to me, “You know, I will probably die of starvation. I have decided to do it in solidarity with the poor of the world who are truly starving. I will have food, but will be unable to eat it. There are millions of people who have no food at all. I think if I could do that, it would ease my suffering.”

Her declaration took my breath away. It was, as Oprah would say, an “Aha” moment. And when I shared my mother’s plan to offer her suffering up for others, I saw the same expression on my friends’ and clients’ faces that I must have on my own, an instantaneous knowing—because on some fundamental level, we know that we are all one.

Or, as Mom wrote, “We carry both pain and joy. Is everything connected? Are the sufferings of children 10,000 miles away related in some way to ours? I cannot address those children’s pain in a hands-on way, but could more awareness, more compassion, make a difference?”

As the weeks passed and her symptoms intensified, I kept pressing her. “Is offering your suffering to others helping you now?” She assured me that it was. “I know that it’s not all about me,” she said. But one particularly hellish day, she blurted out, “I sure hope all this suffering is helping somebody!” This time it was my turn to be the voice of assurance. I said I was pretty certain that it was helping.

And up to her final hours, Mom was full of gratitude. Grateful to see her children. Grateful for her full life. Grateful for a rainy day. During her final week, I asked her what she was thinking. “I’m not thinking,” she said. “I’m just sitting here being thankful.”

Now it is my turn. Mom, I hope you are here, celebrating your life with us. I am so grateful I was able to be with you during your final weeks when you taught me so much about grace and gratitude. I wouldn’t trade a second of that time for anything. I am grateful that you had the courage to see your suffering as a vehicle of transformation, for yourself as well as those near to you, and that your soul is part of eternity. But mostly, Mom, I’m grateful that you were my mother. I love you.

——————–

Laurie Greenwell lives in Austin.