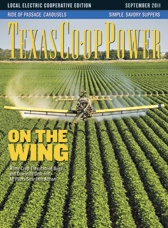

Prologue: Who are those guys flying 3 to 10 feet above the tops of crops at 120 to 130 mph? No, they’re not the crop dusters of yesteryear: They’re now called agricultural aviation pilots—aerial applicators, to be precise—who spray mostly liquid products for one main purpose: to help farmers maximize crop yields and produce food and fiber for a rapidly growing world. In the first of two stories about the ag aviation industry, Texas Co-op Power examines the vital role that aerial applicators play in helping sustain Texas’ agricultural economy.

No doubt, it’s a high-risk occupation: Almost every ag pilot I interviewed has made an emergency landing or knows of a colleague killed in a crash. But these pilots ask the public to understand that they aren’t daredevils deliberately dodging trees, power lines and communication towers for the fun of it. They are meticulous professionals who care passionately about their work and the farmers they serve. In a career field with more and more physical obstructions going up—such as hard-to-see meteorological evaluation towers sometimes erected in a matter of hours—they can never, ever, let their guards down.

As the industry saying goes: There are old pilots, and there are bold pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots.

As a child, I knew a pilot: my maternal grandfather, a Lubbock-area cotton ginner who flew a four-seat recreational plane. I yearned for the day I’d be old enough to go up with him. But in 1968, when I was 6, he was diagnosed with a serious illness and had to stop flying. My chance never came. Yet something was stirred deep inside. I kept my eyes on the sky, watching for small planes—an easy job for a farm kid growing up on the South Plains, where ag pilots zipping over green fields were a familiar sight.

About six years ago, I was driving home to Austin from Bryan on State Highway 21 one summer afternoon. Out of nowhere, there he was: an ag pilot in a tiny yellow plane flitting low across a baby-blue sky. I turned onto a two-lane country road in hot pursuit. Asphalt gave way to dirt, but still I couldn’t pinpoint the plane’s exact location. It kept dipping out of sight, behind trees, as the pilot swooped low for passes over an unseen field.

I pulled over and watched, spellbound. Who are these guys? My journalistic resolve was set: Someday, I would write about these pilots and maybe, if I could be so lucky, even ride with one. (My story of landing a demonstration flight in a two-seat ag aviation training plane is on tap for November.)

To better understand the world of aerial applicators, I visited Brett Whitten, who owns Whitten Flying Service near Snook. The first detail I learned is there’s no such thing as a typical day for an ag pilot/rancher—especially during a drought that’s burning up crops and drying up stock tanks.

Whitten, who took over the spraying business and a cattle operation from his father, the late Jon Whitten, is a lot like the farmers he serves: He works hard to make ends meet. But on some days, his plane never gets off the ground.

May 6, 2011. A faded orange wind sock hangs limp on a metal pole near a paved runway. Inside a hangar, a man is standing beside two airplanes, but I’m not sure whether he’s Brett Whitten, the friendly ag pilot I met in January at the Texas Agricultural Aviation Association (TAAA) convention in San Antonio.

This is, after all, Brazos River Valley country, where fertile farmland traditionally is served by several aerial application businesses in the Bryan/College Station area. I’m in the right place—County Road 270 about 1 1/2 miles southwest of Snook—but it’s possible I’m at the wrong hangar.

“Are you Brett?” I ask the man wearing sunshades and a once-upon-a-time white TAAA cap.

“Yes.”

“Uh, you’re expecting me, right?”

“Yes.”

Long, awkward silence. Whitten’s dog, a poker-faced, brown and white Australian shepherd, gives me the once-over. A young man wrestling with a small, electric pump glances up and looks back down.

“Brett, line 1,” rings out the voice of Whitten’s wife, Mary, over the outdoor intercom system.

“Were you lost?” Whitten finally asks, not smiling. “I saw you drive by.”

I blush. “Uh, no, I just thought, well, you know, I didn’t see your sign, so I kept driving to see if there was another hangar …”

Long, awkward silence. “I didn’t know you flew Air Tractors,” I finally blurt out, recognizing the signature yellow and blue paint of the world’s largest maker of ag aircraft.

Just like that, there it is: a Brett Whitten smile as warm as the morning sun. These are Air Tractor 301As, he explains, one of the first modern-era ag planes made by the globally renowned, North Texas-based company. One plane just got its overhauled engine back from Tulsa, Oklahoma. The other is now grounded with its engine in the same repair shop. He bought the planes used in the mid-1990s, and the ends of the wings look like they’ve been in a fight: Dents bear witness to scrapes with birds, such as buzzards, and small limbs protruding from the tops of trees. Across the wings, patches of peeling, yellow paint expose silvery aluminum.

Both planes have seen countless takeoffs and landings. The operable plane alone has flown about 11,000 hours.

“That’s a lot?” I ask.

“That’s a lot,” he says.

But right now, it’s largely a moot point. What’s being called Texas’ worst drought in more than a century has area crops in a death grip. Even some irrigated crops are being torched. Not much is growing. There’s just not much to spray.

But the good news is that Whitten actually has a scheduled job today: apply insecticide on irrigated research cotton at the nearby Texas A&M University Field Laboratory, overseen by Texas AgriLife Research, where he lands regular work. And this veritable river of conversation has broken the ice. I’m officially introduced to Tank, his constant canine companion, and 20-year-old John Terilli, who’s been working for Whitten since December. Terilli is dating the Whittens’ youngest daughter, Dulce, and they both attend nearby Blinn College.

Tank and Terilli keep their eyes on Whitten, anticipating his next move. Same goes for me. I met Brett and Mary at the TAAA convention, where Brett, who like his father served a term as the association’s president, offered to help me find a ride in an ag plane. In that setting, dressed in a sports jacket and tie, he seemed content to sit back and relax.

Now, I’m on his work turf, and the pencil-thin, fast-moving, 53-year-old is dressed for action: long-sleeved shirt tucked into beltless Wrangler jeans with a sheathed cell phone hooked on the waistband and a Phillips screwdriver in the right back pocket. I’m quickly learning: What feel like unbearably long silences to me don’t exist for Whitten. If he doesn’t immediately respond, it just means he’s thinking. Walk, and then talk. Keep up.

So here’s how the day’s shaping up: Feed the cows. Get the air conditioning running on the operable plane (the heat’s stifling inside the single-seat cockpit). Spray.

Right on cue, Edward “Chooch” Macik, farm research service manager for the Texas A&M field laboratory, pulls up with an Acephate 97UP insecticide delivery for Whitten. Together, they study a map of the research fields. Whitten can start spraying at 4 p.m., when field workers are gone. He needs to be finished in time to make it to a surprise birthday party for his sister-in-law in College Station. “Gotta get ’er done,” he tells Macik.

He’ll be spraying for thrips, early-season insects that suck on cotton leaves and slow growth. Whitten pulls a pen from his shirt pocket and draws a dot on top of an Acephate box: “He’s about that big.”

Time to feed the cattle. Whitten draws a pasture map for Terilli on top of the same Acephate box. “Yes sir,” Terilli replies, expressionless, arms folded chest-high across his black T-shirt as Whitten points out a dry creek bed that he’ll need to drive across.

We head to the hay barn where Terilli’s assignment is to haul big, round bales to the herd. But first, he has to outwit a recalcitrant starter on a John Deere tractor.

Whitten leaves Terilli to it, and he, Tank and I head back toward the green Kawasaki four-wheeler we rode from the hangar. I reach to pet Tank, who’s sitting still as a statue on sacks of range feed cubes in the bed. He glares, and I back away. “Tank’s slow to make friends,” Whitten says, sliding behind the steering wheel.

We drive down the runway, toward the pasture, and my heart pounds as I think about watching Whitten take off later today and then chasing him to the research fields. The pasture’s bone dry, but live oaks stand green beside half-full stock tanks. We approach a herd of crossbred cattle.

“It’s about enough to be a hobby,” he says, chewing on a wooden matchstick and dryly understating the economic importance of the cattle’s health and survival as baby calves scamper beside us with their tails up in the air. He slices open a bag of feed to a chorus of hungry moooos. With cows, calves and a big, black bull on his heels, Whitten scatters the range cubes in a big, walking circle.

Hands on his knees, Whitten studies the herd. He grabs a rope from the four-wheeler, drops it over his head and left shoulder like a quiver and laces the rope’s end through two back belt loops. “What are you gonna do with that rope?” I foolishly ask. “Tie a calf,” he says.

He drives forward about 50 yards, stops, leaves the engine running, slips out, grabs a baby male calf by its back right leg, lowers it to the ground, lashes the rope around all four legs and swiftly castrates the calf before Mama—who’s standing, head lowered, a nostril’s breath away from Whitten—can do anything about it. He ear tags him, hooks a handheld scale to the rope still taut around the calf’s legs and pulls up: “Can you tell me what this calf weighs?”

I squint in the harsh, midday sun. “I’m gonna call it 102,” I nervously offer. Whitten doesn’t question it and records the calf’s weight, tag number (839), color (black with white face) and the date in a red spiral notebook.

Total procedure time: 4 1/2 minutes. Total words spoken by Whitten: eight.

At a stock tank, Tank is allowed to leave the four-wheeler and get a drink. He wades into the brown water, lapping it up, and then happily rolls in the dirt. “Now you can pet him,” Whitten says with a mischievous grin. “Tank, load up. Let’s go.”

At our next feeding stop, Tank eyes a cow with a little too much interest. “Hey … hey,” Whitten says quietly to him. Tank, Whitten explains, takes this pasture stuff seriously. One time, from his perch on the four-wheeler, he bit a cow on the ear. In a fit of rage, she tried to climb inside the vehicle to take out her anger on Whitten instead.

Lunchtime. With me sandwiched between Whitten and Terilli in a single-cab GMC pickup, we head to Slovaceks in Snook. The restaurant/Exxon gas station draws customers from miles around. Inside, we run into several farmers who rely on Whitten’s spraying services.

Jason Wendler, who grows cotton, corn, sorghum, oats, wheat and soybeans near College Station, first hired Whitten’s father three decades ago before Brett took over the flying. Wendler explains that in normal weather years, this area receives generous rainfall. When the fields are too muddy for ground rigs—and crop-threatening diseases and insects are growing like weeds—farmers turn to ag pilots like Whitten who can cover a lot of ground in a hurry.

“You have to have an applicator to get everything done,” Wendler says, noting that plant-chewing pests such as stink bugs, green bugs, aphids, armyworms, head worms, the sorghum midge and three-cornered alfalfa leafhopper, which around here drills into the stems of young soybean plants, can decimate a crop within days.

Whitten and several farmers are congregated near the store’s front door when his son, 26-year-old Sam Brett Jr. “Buster” Whitten, walks in. Buster, a teller at Snook’s Citizens State Bank, who like his parents is a Texas A&M graduate, says hi to the group, grabs some lunch and heads back to work. His father, Terilli and I head toward the research fields. Whitten’s worried I’ll get lost chasing him in flight this afternoon, so he’s showing me exactly where he’ll be spraying.

We’re driving a gravel road through the research fields and listening to the Beatles on a mixed-music CD that Whitten’s oldest daughter, Cherry Whitten, made for him:

“When I find myself in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me, speaking words of wisdom, let it be. And in my hour of darkness, she is standing right in front of me, speaking words of wisdom, let it be, let it be …”

We’re discussing Terilli’s future: Right now, he’s considering becoming a basketball coach. “What about flying ag planes?” I ask. He laughs. No. Staying on the ground is fine with him.

The conversation turns to Whitten: Has he ever been frightened while flying? He smiles, wryly. Last summer, he was spraying here when an engine cylinder broke. “I set ’er down in that corn field right there,” he says, pointing. “But I didn’t have time to get too scared.”

Terilli steals my thoughts: “I have to think my flying career would be about done then.”

Whitten details another incident, some 13 years ago: The engine’s whine grew louder and louder, reaching a screech … and then … nothing. The blower, the engine-driven air intake system, cut out, Whitten says, making a slashing motion across his neck. The engine died, but he landed safely on a gravel road in the middle of a field.

We sit silently, hearing the engine in our minds. “Have you ever made a crash landing?” I finally ask. “Nooooo …” Whitten replies, rapping his knuckles on his cap. He’s merely had what he calls “off-airport” landings. And hitched rides home ending with him walking to the hangar, helmet in hand.

We’re headed back there now. The wind is picking up, and dust devils swirl in the distance. Terilli spots the yellow plane of a local ag pilot. “Oh my God, it looks like he’s too close,” Terilli says as we watch the plane swoop down for spraying passes of normal height—about 5 feet. “That’s crazy.”

Whitten pulls over, and we watch the pilot work. I glance up at the silver guardian angel, a gift from Whitten’s daughter Gillian Whitten, clipped to the sun visor over his head. “Please protect and watch over this family,” the inscription reads.

Miracle of miracles: Back in the hangar, Tank lets me pet him. And soon, Whitten will be taking off to spray the research cotton. My heart’s racing.

A local farmer, Walter Vajdak, pulls up to buy fuel for his two-seat recreational plane. He winds up staying, trying to help solve the air-conditioning puzzle.

Whitten climbs into the cockpit, starts the engine, and the two-bladed propeller spins to life. He climbs down, onto the left wing, with the wind from the propeller whipping his shirt. I, meanwhile, am trying not to notice that the palm trees outside the hangar are starting to sway.

The 70-year-old Vajdak, wearing his cap backward so it won’t blow off, approaches the temperature gauges and hoses hanging from the plane. Whitten lies on his stomach on the wing, his boots planted on the spray boom.

He and Vajdak yell at each other over the roar of the engine. Smiling and hopeful, they hook up a can of Freon and wait.

Nope. Didn’t fix it. The temperature gauge needles haven’t budged off hot. Step two: Change out the compressor. Whitten peers out at the wind sock. For the first time today, he expresses doubts about flying. He and Terilli start the arduous process of replacing the old compressor with a rebuilt one that Whitten has on hand. We all look out at the wind sock. It’s getting a workout. “If it’s stretched out, you’d better be careful,” Vajdak says.

At 4:35 p.m., Whitten makes a cell phone call: Nope, not gonna fly today. The 15-to-20-mph wind would prevent him from effectively spraying. My heart sinks at the news.

Finally, after 6 p.m., the rebuilt compressor is on. Now, it’s just a matter of letting a vacuum pump suck out residual moisture in the lines. But Whitten plans to knock out the spraying job in the morning, despite the status of the A/C. “If I look cool,” he tells Vajdak, “it’s working.”

Whitten looks at his watch: 6:30 p.m. He’s late for his sister-in-law’s birthday party. They’re used to it, he says, smiling sheepishly. Gotta go.

Update: By late June, about half of the pasture’s dozen or so stock tanks have dried up. One night, Whitten works until 11, penning more than 100 head of cattle to be driven by truck to auction the next day.

As Whitten says, he’s not the Lone Ranger. Everybody’s in the same boat, waiting for rain. The future holds many unknowns, such as who will take over his spraying business someday. But Whitten’s proud of his four grown children and their independence. He’ll help ’em on whatever path they choose. Same goes for his two part-time workers, Terilli and Jeff Cunningham, a Texas A&M senior who’s considering an ag pilot or military flying career.

That’s just Brett, Mary explains. Her husband of 30 years will give somebody the shirt off his back and expect nothing in return.

Mary’s eyes sparkle as she describes Brett, a natural pilot who soloed at 14 and was flying an open-cockpit ag plane—an S2C Snow designed by the late Leland Snow, the founder of Air Tractor—when they met in 1980. “To this day, I get a thrill seeing him fly,” she says, adding that the planes might look a little rough, but Brett takes good care of them. “That’s what’s kept me sane all these years.”

Mary laughs. They’re late almost everywhere they go because there’s always one more thing to fix or one more cow to check.

Brett Whitten takes this agriculture stuff seriously. He doesn’t differentiate between the days because the bugs don’t. He feels ownership of the fields he sprays. These farmers, his friends, are counting on him. They’re all in this together.

——————–

Camille Wheeler, associate editor

Our follow-up story will examine the biggest dilemma facing this small industry—retirement: Who will fly expensive aircraft that require high-tech knowledge and old-fashioned tail wheel, stick and rudder flying skills?