Consider, for example, Bob Wade’s six 10-foot-tall dancing frogs.

The artist created them in 1983 as outdoor décor for Tango, a nightclub in Dallas. When a battle ensued over whether this creation was art or signage, City Hall chose to call it art, and the frogs remained—at least until the club went under and the frogs were auctioned off “just like the barstools and silverware,” Wade recalls.

The amphibian sextet subsequently danced for years atop Carl’s Corner, a truck stop served by HILCO Electric Cooperative on Interstate 35 near Hillsboro. Millions of travelers first did a double take when they saw the unlikely figures on the roof. After the novelty wore off, they became landmarks along the interstate, with only a short hiatus to join a statewide sculpture tour curated by Austin’s then-Laguna Gloria Art Museum.

The truck stop burned to the ground in 1990, but the frogs were, astonishingly, untouched. The sculptural troop was broken up, as three frogs moved to Houston then later hopped to the roof of a Chuy’s restaurant in Nashville. The other three languished across the freeway from the former Carl’s Corner at the home of Carl Cornelius himself. They made a brief appearance when Willie’s Place opened at the truck stop, but that didn’t last, either.

Then, in summer of 2014, the Taco Cabana chain bought the three for a new restaurant at—get this—the old Tango location in Dallas. They were refurbished and hoisted to the roof of a building on the same spot where they started. A happy ending, says Wade.

Much of this saga felt familiar to the artist. In 1978, he created a 40-foot-long, slightly belligerent-looking iguana for the Lone Star Café on Fifth Avenue in New York City. “When the iguana went up on the roof, some people got up in arms and said the lizard was illegal signage,” Wade says. As happened with the frogs in Dallas, Wade’s work was declared art, this time in court. The complaints didn’t end, though, and the iguana was later dismantled to hunker below the building’s roofline. A few years later, Mayor Ed Koch asked someone, Whatever happened to the iguana? His people made some calls and, Wade recalls, “Next thing you know, I’m overseeing reinstallation of the lizard, with Texas Gov. Mark White in attendance. It was one of my finest moments.”

Then the café closed in 1989, and the iguana, too, suffered the ignominy of being auctioned off like spare furniture. Yet this story, too, has a happy ending: In 2010, the refurbished reptile was lifted by helicopter to top the hospital building in the Fort Worth Zoo. A documentary about the sculpture, “Flight of the Iguana,” is in production.

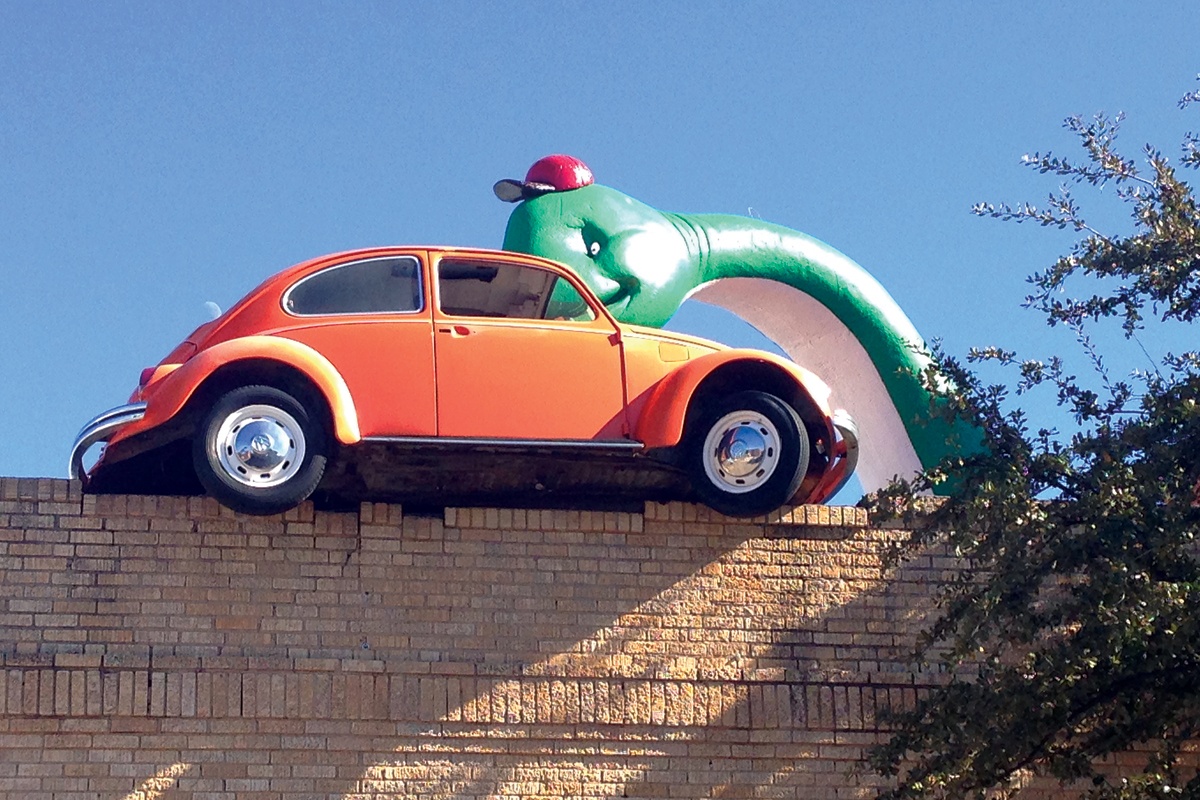

Wade also created a 40-foot-tall pair of cowboy boots that, since 1979, has served as a landmark for San Antonio’s North Star Mall. An enormous saxophone he built for a club in Houston in 1992 has hubcaps for keys, two beer kegs and a surfboard for the mouthpiece, and an upside-down Volkswagen Beetle for the bell. That club also closed, and the saxophone has been dismantled—no small feat, Wade points out—and now belongs to Houston’s appropriately quirky Orange Show.

A teardrop trailer topped with a giant replica of Kinky Friedman’s cowboy hat (and cigar) made the rounds during Friedman’s 2006 bid for governor then disappeared before resurfacing in Lockhart. Then there was Dino Bob, another VW-based sculpture that overlooks downtown Abilene.

The sculptures start with electrical conduit and galvanized steel pipes bolted together to form the internal structure. Wade then creates a rough shape using heavy wire mesh, adding finer details with window screen wire as needed. This framework is then covered with spray-on urethane foam insulation, which hardens and can be carved. Structural additions, such as Volkswagen bodies or, in the case of the iguana’s spines, sheet metal, are added along the way, and, lastly, the sculpture is painted.

“Quirky and outsized” describes Wade’s own saga as well as his sculptures. His family moved around for his father’s work in hotels, living in Galveston, Beaumont and Marfa before landing in El Paso, where teenage Bob joined a hot rod club. He drove his customized 1951 Ford Victoria hard-top convertible to enroll at the University of Texas in 1961, creating a stir when he pulled up at the Kappa Sigma fraternity house. The buttoned-down brothers from Dallas and Houston hadn’t seen anything like the car or its outgoing, long-haired, bearded driver, and dubbed him “Daddy-O.”

Today, the hair has thinned, the beard has turned white, and the car is long gone, but the name sticks. It’s used by most of his friends and the waitstaff at Shoal Creek Saloon in Austin—a building adorned with a giant New Orleans Saints football helmet that Wade built from the carcass of a VW bus. Daddy-O often occupies a table there, effortlessly pouring forth fantastic stories of his sculptures, his photographs and his friends, most of them famous or infamous. One story leads to another, and another and another.

Wade also admits to a conventional side: He earned A Fine arts degree from UT and a master’s in art from the University of California, Berkeley. He taught art at the university level for 12 years and exhibited his more conventional art in major galleries in Santa Fe and Dallas. His large, colorized canvases of old photographs hang in high-rises, offices, prestigious art museums and homes throughout Texas and beyond, including the royal palace in Monaco. Three belong to the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos.

Wade’s photography adds a sense of humor and satire to the Wittliff’s Southwestern and Mexican imagery, says curator Carla Ellard. “Wade reinvents vintage photographs and postcards by airbrushing them using transparent layers of acrylic paint and sometimes hand-painting with oil paint. His image of ‘Solda-dera,’ originally taken during the Mexican Revolution, brings to light the role of women during a violent time in Mexico’s history. His ‘Rodeo Cowgirls’ is just plain fun—giving new life to a vintage image by adding color.”

Austin writer and speaker Dan Bullock, a longtime friend, calls Wade’s use of color stunning. “He can turn a black-and-white photograph into an amazing piece. It takes a real steady hand and an incredible eye. His past couldn’t have been as wild as he’d like you to believe for him to be able to do that.”

Yet the artist cheerfully claims his inner Daddy-O. “It’s not so bad to have a nickname to go along with your career,” he says. “I’m a little far out, not the average person. Who knows what’s around the corner? I get goofy calls all the time.”

The latest such call came from Castle Hill Partners, which owns Hope Outdoor Gallery, a wildly painted street art site in Austin, asking for a sculpture. Wade decided to play off the acronym for the gallery, HOG, and the nickname for Harley Davidson motorcycles, hogs. An oversized (of course) motorcycle made out of parts from Harleys and ridden by a javelina (aka a hog) made partly out of beer kegs will be, Wade says, “Daddy-O’s latest goofy thing.”

Wade prowls postcard shows and junk shops for images to use in his photo murals and odds and ends to incorporate into his sculptures. These finds fill the converted garage and carport that serve as his studio behind the West Austin home he shares with his wife, Lisa. The effect is a kind of a free-form museum of the life and times of Daddy-O.

Old postcards organized by subject fill a closet, boxed canvases line one wall, stacks of photographs cover tables, and shelves overflow with toys, trinkets, memorabilia and doodads. Somehow, Wade seems to know what all he has and where everything is, along with an idea for what to do with most of it.

Wade shows no signs of slowing down, and his words of wisdom to aspiring artists are telling: “Go as fast as you can for as long as you can.”

It seems to work for Daddy-O.

——————–

Melissa Gaskill is an Austin writer.