A six-week-old baby girl is being christened in a country church outside Lubbock. Her mother, my cousin, wears a pink designer dress and a cartwheel hat covered with red roses. Her father wears a suit and hand-tooled boots. But Emma, the baby, is clad in a gown of feed-sack material. The tiny frock is as soft as butter and the color of Guernsey cream. And it is beautiful.

Feed sacks! No way!

After the ceremony, the women in the congregation rave about the baby’s christening dress and want to know if it is French. The young mother proudly proclaims, “Emma’s dress isn’t French. It’s the dress my great-great-grandmother made for her first child. And she sewed it from feed sacks. Look, she even unraveled the string that stitched the seams and saved it to crochet a lacy hem on the gown. All the children in our family have been christened in this dress.”

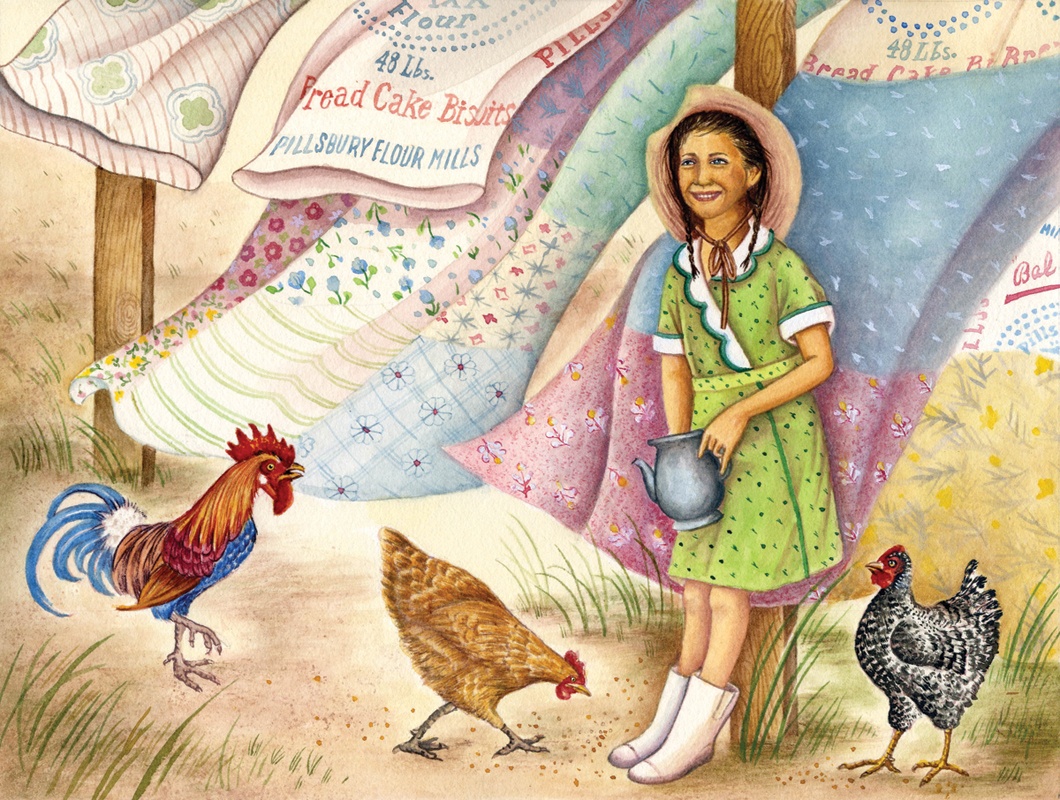

Baby Emma’s dress was one of many made by rural Texas women who recycled relentlessly during the hardscrabble 1920s and 1930s. They “made do” because money was scarce and hard times were a fact of life. Not a usable scrap of fabric was wasted.

“Use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without” had been a motto since Civil War days. But that didn’t mean these women didn’t long for pretty things. In those days, the cloth bags that held chicken mash, cattle and horse feed and kitchen staples such as flour and sugar were highly prized for use in quilts, tablecloths, pillowcases, dresses and dolls. Patient women would even rip open tiny Bull Durham tobacco sacks, wash and bleach then dye them and, several hundred sacks later, piece a quilt using them.

Feed sacks were originally made of plain muslin, but by the 1920s, manufacturers got savvy and printed the cloth in colors, as well as prints, plaids and flowered patterns. As a further enticement to seamstresses, most of the bags were sewn together on a chain-stitch machine, which made the seams easy to open.

Buying feed for animals and people was a necessity, so competition among manufacturers sizzled. Some feed companies sent salesmen out, not to question the farmer about the feed he needed for his livestock, but to ask his wife what she wanted in the way of patterns on the fabric: checks, stripes or flowers.

One woman, who collects vintage feed sacks today, remembers dresses she wore that were sewn from chicken mash sacks.

“During the Depression,” she says, “we had a flock of white leghorn hens. Sometimes it was hard to scrape up enough money to feed those cackling biddies. The only bright spot was that the feed came in sacks of pretty prints of pink and blue. After my dad emptied the feed into a container in the chicken house, my mother and I could hardly wait to grab and unstitch those bags, wash and iron them and smooth our dress patterns onto the material. Usually we went along when he bought the chicken feed so we could make sure we got the patterns and colors we wanted.

“By stitching the bags together, we also made large items like sheets, pillowcases and tablecloths. We called those items our ‘chicken linens.’ ”

In some towns, feed or grocery stores managed a feed sack exchange program. If customers had sack material they did not want, they could replace it with another one from a stack on the store shelf for a nominal sum.

But not all feed store merchants were thrilled about the change in sacks. One merchant complained that, “Years ago they used to ask for all sorts of feed, special brands. Now they ask me if I have an egg mash in a flowered percale. It just doesn’t seem right.”

Women who had access to more sacks than they could use added to their butter-and-egg money by selling their extras to neighbors or friends. Feed sacks were often repurposed to make underwear. Because these garments were not to be seen, busy farm women did not always remove the manufacture’s logo and printing on the underwear. Pity the fellow who had his underwear made from a Ralston Purina sack: That logo sported a mule.

This use of feed sacks continued until after World War II. During the war, textiles were scarce, with everything going to the war effort. Feed sacks sometimes were printed with victory slogans and scenes such as raising the flag on Iwo Jima. Others pictured characters from “Gone With The Wind,” “Cinderella” and “Alice in Wonderland” as well as space designs from “Buck Rogers.” Nursery rhyme characters like Bo Peep and Humpty Dumpty were favored for baby clothes, blankets and quilts.

By the 1950s, manufacturers started constructing their sacks from heavy paper and other materials cheaper than cloth. That put an end to feed sack clothing, created due to the shortage of money during the Depression and the shortage of cloth during World War II. During those years, feed sacks made it possible for thousands of resourceful women to create items both pretty and practical that they yearned for but could not buy.

——————-

Juddi Morris lives in Gainesville.