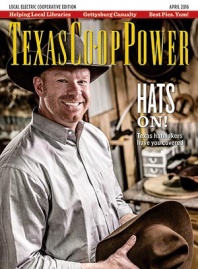

It’s hard to imagine a personal accessory more world-famous than the cowboy hat. Here in Texas, we might even be tempted to think that the first humans to set foot within present state boundaries wore the distinctive headgear upon arrival.

While that perception stretches the blanket, it’s not an exaggeration to say that—despite the fickle flights of style and trend—the classic cowboy image is as popular as ever. And when it comes to “goin’ cowboy,” whether fauxpoke or genuine article, much of the mystique is all about the hat.

Many of the store-bought Stetson and Resistol hats sold in the state are produced at the Hatco factory in Garland. For a more exacting fit, you can order a cowpoke chapeau custom-made by an expert independent hatter. Either way, when you crown your cranium with a cowboy hat, you’re struttin’ your stuff in the bootsteps of a grand and storied tradition.

Tracking the origins of that tradition, as one Texas hatter put it in a previous century, is “like following a twisting coyote trail.” Spanish and Mexican vaqueros wore versions of the wide-brimmed hat as they spread cattle culture northward into Texas and across the Southwest. Westering settlers adopted the protective headwear, too, and in 1865, Philadelphia hatmaker John Batterson Stetson introduced his “Boss of the Plains” hat. By the cattle-drive heyday of the 1870s, Montgomery Ward catalogs offered the “Texan Chief Cow Boy’s Mexican Style Sombrero Hat” for $5.34.

Western movie stars established the cowboy hat as an American cultural icon in the 20th century, and country-western singers further solidified its timeless appeal. When one of Ernest Tubb’s Texas Troubadours asked if he could perform sans Stetson, Tubb offered to let him off the tour bus. George Strait continued the tradition when he first went to Nashville in the early 1980s, though record executives tried in vain to get him to “lose the hat.”

Not long ago, when hatmaker and aspiring country singer Brooks Atwood wore his hat into the Nashville offices of MCA Records, an executive smirked, “All we need is another Texas hat act.” Bristling, the East Texas cowboy shot back, “This hat ain’t no act.”

The songwriting buddy who had accompanied Atwood to the meeting recognized a hit lyric hook when he heard one. “Don’t say that phrase out loud again!” he whispered. “We gotta write that song!” This Hat Ain’t No Act is the title track on his 2014 release.

Like many hatmakers, Atwood, whose family and business are members of Trinity Valley Electric Cooperative, began appreciating cowboy hats as a toddler, romping around wearing the hat and boots of his father, Dick Atwood. An 84-year-old Frankston-area rancher, the elder Atwood says he started making hats after years of looking for one that would work hard in the hay fields and branding pens and then still look good on trips to town. One of the few Texas companies that makes hats in bulk for retail stores and custom hats specially fitted to a customer’s head, Atwood Hat Company started out with three styles in 1996 and now offers more than 125 styles with names like Van Horn, Sweetwater, Langtry and Rodeo Del Rio.

Jeff Biggars uses a conformateur to get a precise fit.

Tadd Myers

Biggars blocks a crown, one of the first steps in crafting a hat.

Tadd Myers

Biggars smooths the felt on a hat.

Tadd Myers

Biggars applies steam as he shapes a hat.

Tadd Myers

“Some of the designs these days are different and crazy,”says hatmaker Jeff Biggars, who opened his western wear and custom hat outpost, Biggar Hat Store, on the Decatur square in 2013. “The vast majority of straws used to be plain white, in three styles. But when I worked as a designer for American Hat Company in Bowie, we started doing more colors and some wilder weaves.”

Taller crowns with smaller brims used to be more popular, too, but today’s tastes often reverse those dimensions. Biggars’ Red Dirt Special custom felt design features a big 5-inch brim. “We call it a super punchy hat ’cause it’s preferred by cowpunchers,” Biggars says. But his favorite custom hat is his Eighter From Decatur, named for a classic gambling expression that became the title of a song by Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys.

Western hats for women also have surged in popularity. Hatmaker J.W. Brooks of J.W. Brooks Custom Hat Co. in Weatherford and Lipan gets artsy with his Neon Cowgirls line inspired by Dale Evans and Roy Rogers and other sagebrush fashionistas of the 1940s and ’50s. Brooks creates designs on the undersides of his upturned brims that give his women’s hats a blingy zing. Hatmaker John Davis of Limpia Creek Hats in Fort Davis adds that bolero-style hats, with a flat top and brim, are also in demand. “They dress ’em up with bound edges and triple bows,” Davis says.

Despite style trends that come and go, any custom hatter will still build you a basic, old-school cowboy hat. “Our own style has never changed,” testifies James Andrae of Capital Hatters in Stephenville. “We specialize in good old quality western hats.”

J.W. Brooks irons a hat at the J.W. Brooks Custom Hat Co. in Lipan.

Tadd Myers

Brooks applies an iron to a hat.

Tadd Myers

J.W. Brooks stitches the inside band into a hat.

Tadd Myers

Brooks draws a custom stitch design that will adorn the underside of a brim.

Tadd Myers

That “old” theme is reflected not only in the tried-and-true hatmaking process but also in the antique equipment used by hatters. First, they measure your head with a sci-fi-looking gizmo called the “conformateur.” At Spradley Hats in Alpine, Jim Spradley’s conformateur was made in Paris in the 1850s. Then the hatter “builds” the hat from a “blank,” a hairy, conical piece of raw felt that hatters buy from hat-body factories. Pure beaver fur makes the best and most expensive felt hats, but wild hare fur and wool are also used.

Placed in a blocking machine, the hat body is pulled in all directions as steam latches together the microscopic barbs on the fur to create the hardened felt. A poplar block is inserted to create the hat’s size and crown height, and then the fibers are reshrunk with a blast of cold air. After a two-step ironing process, the felt is sanded, and the brim is trimmed on a plating machine. Finally, the hat is hand-shaped with the customer’s head template.

In addition to making hats, some hatters also restore them. “A lotta old hats have been whooped up bad,” says 23-year-old hatter Seth “Johnny” Bishop of Johnny’s Custom Hatters in Longview. “As long as it’s beaver and the color isn’t gone, we can usually bring it back.” Biggars recently restored a cowboy hat that had been crushed and magic-markered by its owner’s angry ex.

Conversely, some hatters will distress a hat—make a new hat look old. Biggars distressed the hat Daniel Day-Lewis wore in the film There Will Be Blood. “He won an Oscar for the role,” jokes the hatter, “and I think I should’ve gotten an Oscar for the hat.”

Many customers request a hat like one they’ve seen in a movie or one that is worn by a favorite musician. “I get a lot of orders for John Wayne hats and the hat worn by Tom Selleck in Quigley Down Under,” says Murchison hatter Rex Fleming. “Another favorite is a hat worn by the late blues guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan, and I also get requests for hats like the one I made for singer Ray Wiley Hubbard.” The high-crowned “Gus hat” worn by Robert Duvall in the television miniseries Lonesome Dove is also a perennial favorite.

“A cowboy hat is an extension of your personality,” Biggars says. “I can tell a lot about a person just by lookin’ at their hat.”

Biggars holds a finished hat in his shop on the Decatur square.

Tadd Myers

The inside of a hat made at the J.W. Brooks Custom Hat Co.

Tadd Myers

The inside of a hat made at the Biggar Hat Store.

Tadd Myers

Biggars checks the symmetry of a hat.

Tadd Myers

Biggars hand-sands the felt.

Tadd Myers