First this business with the name—Great Texas Balloon Race. This annual event in Longview is as much a race as the Super Bowl is a beauty pageant. It’s not timed. There are no photo finishes. The prize goes not to the swiftest, nor the fittest, most persistent or the one with the razor reflexes.

No, to win the GTBR, a balloonist must be without peer at doing the math in his head; making U-turns; not letting being lost ruin the day; throwing beanbags at targets and playing ring toss; and, above all, staying poised. The winner must be the best at being decisive while questioning everything, and, when it’s all on the line, playing hunches and having faith that the oft-fickle winds of fortune literally have his back when he needs them most.

Kind of makes a race look simple.

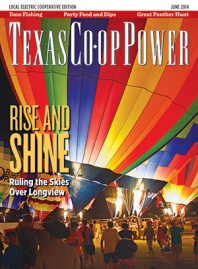

It’s 5 a.m. on the last Sunday in July 2013. Today is the final day of competition in a weeklong series of trials, about half of which have been scrubbed because of weather. A ground fog covers the low land surrounding East Texas Regional Airport, and a half moon glows above. Slowly the parking lot begins filling with pickups and vans, modified with back lifts that are carrying large wicker baskets with sturdy aluminum handles. It’s either the world’s largest picnic or ground zero for the Great Texas Balloon Race and the U.S. National Championships, which run concurrently from 2012 through 2015.

The Great Texas Balloon Race traces its origins to 1978, when Bill Bussey, a Longview dentist and world-record-holding hot air balloon pilot, agreed to drag a banner behind his balloon touting the opening of a local shopping mall in return for backing for a balloon race. Today the GTBR is one of the premier gatherings in the country, drawing more than 100 racing and novelty balloons annually for the three-day event.

Pilots and their ground crews mill about, making nervous small talk and sampling doughnuts and coffee. A couple of pi balls, helium balloons with strobe lights, are set loose to test wind conditions. One heads east. The other starts west.

At 6 a.m., the doors to LeTourneau University’s Abbott Aviation Center open, and the pilots, already queued up, quickly file in.

For the next 15 minutes, after getting GPS monitors and souvenir coffee mugs, they’re briefed on the tasks they must complete, the location of the perimeter outside which they must launch, wind and weather conditions, and forecasts at varying altitudes. There are two kinds of balloonists: floaters and flyers. Floaters just enjoy being in the air. Flyers try to get from Point A to Point B. Today, they’re all flyers.

Outside, in the middle of a long row of 62 vehicles parked side by side, like a ready row of F-16s on alert, Bill Adler’s crew sits patiently in a red Ford van. Jean, his wife, is in the passenger seat. She’s the reason they’re here. Thirteen years ago, she wanted a balloon ride and, in Bill’s words, “one thing led to another.”

In the middle row are Ramey Carroll, his son, Tanner, and Sam Robey, 52. In the back are a photographer and a writer from Texas Co-op Power who pledge to shut up and stay the heck out of the way. In the ignition are the keys.

The plan is simple. Jean Adler acts as crew chief, handles the GPS readings and talks with other crews to share ideas. Robey programs the GPS and, along with Ramey Carroll, helps put the rig together. Tanner Carroll, 20, still carrying the muscle that allowed him to play offensive line at nearby Pine Tree High, provides the beef.

Preparation requires more than just manpower and time. Guy Gauthier, 68, a Longview balloon builder—he rigs them for launching—says a new balloon can cost $20,000. Top-of-the-line racing balloons, shaped more like footballs than inverted raindrops, can approach $100,000.

“Just to buy a good used balloon can run $15,000 to $17,000,” says Richard James of Diana, a balloonist and member of Upshur Rural Electric Cooperative. “I know people who pay nearly that much to play golf year-round.”

Most of the balloons have sponsors. LeTourneau University sponsors Adler, 71. Pat Cannon, a two-time national champion and member of Rusk County Electric Cooperative, says funding is the least of a pilot’s needs. “What you really need more than money are really, really good friends,” says Cannon, who took third place at the 2013 nationals. “You have to have people who are willing to get up at zero dark thirty and drive all over creation and crew for you.”

‘This is Where it Gets Fun’

Adler’s crew members are ready to roll. They will use the maps in their minds and on their laptops and suss out the best places to launch. If they get there first, they’ll launch a helium test balloon and watch its ascent with binoculars and a compass to determine if they’re in the right place at the right time to take advantage of the varying wind directions at that spot at different altitudes.

If it’s right, and they’re on public property, they’re golden.

If it’s right, and they’re on private property, they must get the often-sleepy landowner to sign a release saying it’s cool to launch on their property. The Adlers already have a secretly delicious plan: They’ll launch in their own front yard on Lake Cherokee about 2 miles away, should conditions permit.

Within 10 minutes, the skittish winds will literally blow the plan apart.

It’s 6:15 a.m. The Abbott Center’s doors open and the pilots bustle out. Some run. Most, the experienced ones anyway, walk. They must launch before 7:30 a.m., but other than that, there is no real urgency. Adler reaches the van and the plan goes into action.

Tanner Carroll turns to the back seat and smiles. “This,” he says, “is where it gets fun.”

For the next 99 minutes, it’s fun if your broad idea of fun includes liberal interpretations of the Texas Motor Vehicle code; a series of launching spots that don’t pan out; inevitable U-turns and impromptu off-roading; and the constant peppering of coordinates, bearings, GPS numbers and wind direction. There’s the thrill of the fog limiting visibility to about 100 feet—tops—and of a delivery truck heading straight at the van stopped in the turn lane as its driver stares intently at the balloons hovering over the airport. “Do you think he sees us?” Jean Adler asks, sounding as worried as she’ll get this morning. A blast of the van’s horn and the sudden jerk of the delivery truck’s steering wheel by the startled driver answers that question.

Adler’s crew makes six U-turns, tears down a couple of one-lane roads, releases two pi balls, shouts out coordinates like an artillery spotter and drives about 25 miles to travel one. The spot they choose is on the other side of the fence that bounds the southeast corner of the airport.

“It’s not an exact science,” Jean Adler shrugs.

This is the spot. It’s got the right clearance, right wind, right range … but the Adlers have the wrong balloon. The night before, he flew his balloon called Wildfire over the crowd as part of the nightly fan festivities, which include demonstration flights, some character balloons and the dusk glow, when the burners are cranked for a few seconds to create a sea of light and color. Adler forgot to change balloons. Fortunately, he lives only 15 minutes away.

He makes it in 10.

All but one of the dozen or so balloons that will launch from the same property are airborne before Adler returns. His crew springs into action, unstrapping Spitfire, stretching it out, attaching it to the basket, fitting the GPS and laptop to their mounts, blowing air into the balloon with a giant fan and then heating that air with a burner powered by three propane tanks, each one able to keep it aloft for 30 to 45 minutes, depending on air temperature.

Seven minutes later, they’re ready. The Adlers kiss, and Bill says, “I’m gone,” hits the burner and eases into the air.

This is his moment, but the crew lives vicariously. Tanner Carroll, an Eagle Scout who just finished his sophomore year at Texas A&M University, got introduced to ballooning through a connection from Cub Scouts. Ramey Carroll crews because his son loves it so, and he values the bonding time.

Pilots are drawn to ballooning for varied reasons, but most have to do with the tranquility and feeling of going with the flow of nature. “I love the idea that I really can’t control it,” James says. “You have some control, but God and the wind determine where you go.”

Says Tanner Carroll: “You get up in an airplane, it’s fascinating, but in a balloon, you’re free with the elements. It feels like the ground is going away from you instead of you going away from the ground.”

Sticking the Landing

That peaceful, ethereal, kumbaya feeling isn’t guaranteed.

At the 1986 National Championships in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Cannon heard a rifle bullet whiz by and looked down to see an irate landowner aiming at his balloon, perhaps fearing an alien abduction or a discovery of his secret brewing operation—or just overly persnickety about his airspace. Cannon didn’t stick around to find out. He recorded the GPS coordinates and, upon landing, alerted the local sheriff, who paid the man a visit to discuss the felony crime of shooting at aircraft.

Lee Ratcliff, 65, who’s been crewing for 15 years, values the friendships. “I don’t really know why I get up at 5 a.m. all week to do this,” he muses. “Well, the people are friendly; there’s a certain camaraderie. It’s not like NASCAR drivers, who’ll get into a fistfight after one nudges the other—and there is some nudging here.”

Often it comes when the pilots are attempting one of the two skill tasks, the ring toss. The idea is to control your altitude such that the crosswinds take you right by the 20-foot pole, and you can simply reach out and slip the 12-inch ring over the top, the equivalent of a basketball dunk. “I’ve been bumped away more than I care to remember,” says Cannon, who’s also dunked more than a few.

Acing the ring toss brings a $5,000 prize. If more than one pilot does it, the first one gets $1,000 and splits the remaining $4,000 equally with the other winners.

On this day, Adler doesn’t even attempt the ring toss. He’s too far away. He missed with his first projectile during the beanbag toss, in which a pilot must hit a target on the ground with the first bag and then try to get close to the first beanbag with the second. Now, getting anything out of the skill portion is moot.

He’s been in the air 17 minutes. With his tasks completed, he looks to land. Being a local, he knows where to look. He spots a clearing between two cul-de-sacs a little over a quarter mile from one corner of the airport.

Jean Adler already knows where he’s heading. She pulls the van onto Anita Street and slams the transmission into park. Locating a landing spot is more difficult than finding a launching point. Sometimes you have to set down without permission. Ratcliff remembers one pilot setting down on a soccer field that looked public but wasn’t. And it was locked. But Ratcliff played a hunch. Many such facilities simply use some form of the street address as the lock combination. Ratcliff’s hunch was right.

Cannon also once landed in a cul-de-sac deserted save for a parked car in which a couple was engaged in flagrante delicto in the back seat. “Both of them jumped out buck naked and ran,” he laughs.

This landing is relatively routine. In her house across Anita Street, Toya Moore hears the roar of the burner. “I told my son, ‘I think a balloon is landing outside our kitchen window,’ ” Moore says. Instead, the balloon is a good 100 feet away. Moore takes a few snapshots with her camera phone and buries her face in the keypad. “I’m going to put on Facebook: ‘This is what I woke up to!’ ”

The whole flight has taken less than 20 minutes. The crew patches a quarter- size hole in the fabric, disassembles the rig, rolls up the balloon and slides the basket on the lift. Their day is done.

Adler goes to the race website and checks the standings. He’s holding at 35th place.

“If I stay 35th, I’ll be tickled,” he says. “Last year, I was 45th. Next year, I’ll be 25th or better.”

When the final standings are posted, he’ll have slipped to 37th, but Adler remains undaunted. He’s confident that in 2014, the skies will be clear, the temperature right, the ring toss will be a slam-dunk, the beanbag throws will be true and the winds of fortune will have his back. Maybe he’ll even get that backyard launch after all.

——————–

Mark Wangrin is an Austin writer.