I’d had a great day catching my limit of red snapper, but eight hours on a boat out in the Gulf of Mexico under a summer sun wrings out a lot of energy along with the sweat. Now, though, having enjoyed a long shower and fried shrimp for supper, I sat with my wife on the balcony of our rented condo four stories above a South Padre Island beach, taking in the surreal scene below as dozens of moving flashlight beams played back and forth across the sand.

The roar of the surf all but washed out the excited squeals of the kids below as they scurried here and there chasing ghosts—ghost crabs (Ocypode quadrata). It’s the seaside version of catching fireflies and putting them in a jar, except that the crabs are bigger than bugs, about the size of a small child’s fist.

Our daughter Hallie opened the sliding-glass door and joined us on the porch. “Daddy, I want to go catch some crabs,” she said. I tried at first to beg off, but she persisted. Finally, realizing how disappointed she would be if we didn’t go, I gave in. Looking back, I’m sure glad I did.

Ghost crabs, whose pale coloring blends in so well with the sand that they seem to disappear, are so named because they primarily come out at night to scavenge the beach for food—from sand fleas to dead fish. During the day, these crustaceans spend most of their time digging, cleaning and repairing their burrows. And they dash to the water’s edge several times a day to wet their gills, thereby enabling them to extract oxygen from the air.

With large, black eyes on the ends of long, vertical stalks, ghost crabs have excellent 360-degree vision—and a startling appearance. They also live up to their genus name, Ocypode, which is derived from a Greek phrase that means “swift-footed.” When ghost crabs spot something threatening or bigger than they are—like a little girl with a flashlight and a green plastic bucket with a yellow handle—their eight legs can propel them up to speeds of 10 mph.

Operating on pure fight-or-flight instinct, the crabs don’t realize it’s all just a game when a kid is on their trail. If captured, they don’t get cooked or even kept for “life.” A seasoned crab chaser, Hallie only holds them in her partially sand-filled bucket overnight. She releases them on the beach the next morning, none the worse for wear.

On a good night, she can round up a dozen or more crabs in an hour. And each year, she gets better at it. Now on the verge of being too cool for such childish behavior, especially with her dad tagging along to offer an extra light as well as parental supervision, she could offer ghost-crabbing lessons:

- The bigger crabs, maybe 3 inches wide, tend to be found farther from the surf.

- Those larger crabs, though not as common, run slower and are easier to catch.

- Bigger crabs are best captured by throwing sand on them. When the sand hits them, they usually stop running and dig in. But they seldom get deep enough to save themselves from a bucket ride.

- Sometimes, a particularly sizable crab will turn and stand to fight, its pinchers snapping menacingly in the air. Keep the crab occupied while your buddy sneaks around and catches it from behind. And try not to let it pinch you.

Despite the experiential knowledge Hallie has gained on our annual trips to South Padre, a crab taught father and daughter a lesson neither of us has forgotten.

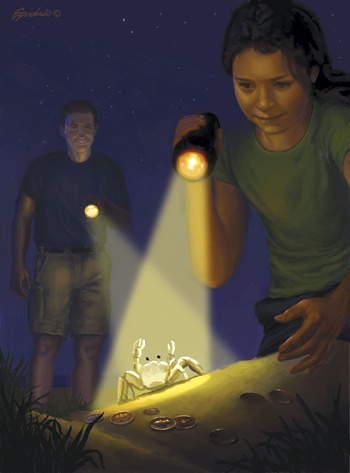

As we walked along the beach on the night that I tried to get out of going with her, Hallie’s flashlight beam soon locked on a hefty crab scooting rapidly across the sand on its spindly legs. I tried to keep my flashlight trained on it as it zigged and zagged. The chase went on and on, a human-crab version of “America’s Scariest Chase Videos.” Finally, Hallie got it cornered, tossing a handful of sand on it.

“It’s daring us,” she said, moving in for the capture. I looked closer and saw its larger of two claws extended and ominously opening and closing in a silent warning to back off. Then I spotted something shiny in the circle of light my flashlight made: coins. The feisty crab had drawn its figurative line in the sand surrounded by coins. “Looks like somebody lost some money,” I said.

Hallie waited for the right moment and snatched the crab as I started collecting the scattered coins—an assortment of quarters, dimes and nickels. Catching her breath after the spirited race, Hallie began to process what had just happened. “He led us to treasure,” she said. “He paid for his freedom.” Thinking for a moment, she added, “I’m gonna let him go.”

“Good idea,” I said, busy counting the ransom money.

As treasures go, it wasn’t much. A little more than $3, barely enough for a caffe latte. But treasure, I began to realize, is not just money. That night’s real treasure was the chance to experience a real-life fairy tale with a young princess. Not only had the crab led us leprechaun-style to a small pot of gold—well, contemporary silver coins—it had turned the tables and captured us in a special father-daughter moment.

As I pocketed the gritty change, Hallie reached in the bucket, pulled out the crab and gently released it. We both watched as it hurried away, its own story to tell.

——————–

Mike Cox is a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power.