As a Texas boy, born and bred, I thought I had a pretty good grip on the interesting, big and weird things that had gone on around these parts, especially regarding critters. I didn’t know much about Chupacabras, the legendary bloodsucking cryptids supposedly killing livestock in parts of South Texas, but I have had a beer with the deceased, stuffed Clay Henry III, the former goat mayor of Lajitas (and permanent fixture of the Starlight Theatre in Terlingua), and I saw “Hawmps!” a couple of times as a kid, so I was familiar with the short-lived U.S. Camel Corps out at Camp Verde in the mid-1850s.

Both yarns were fascinating and tough to beat, but Texas is a vast, strange place. And last summer, I unwittingly stumbled onto a story that overshadowed them both.

In early August, I lit out toward Rocksprings in Edwards County, not in search of outlandish critter tales but to take a guided tour to Devil’s Sinkhole. Part of Devil’s Sinkhole Natural Area, the sinkhole is a collapsed, vertical cavern approximately 40 by 60 feet at its mouth and reaches depths of 350 to 400 feet. From a distance, it’s a harrowing black puncture in the hard limestone of the Edwards Plateau. But up close, you see that the immediate vertical drop is around 140 feet and the walls down are dotted with green plant life. It’s dramatic during the day, but at night it becomes astounding.

At or around dusk, the sinkhole mouth fills with Mexican free-tailed bats slowly rising from the depths in a spiral. Devil’s Sinkhole is home to nearly 4 million of these winged critters, and they soon blot out the waning sunset as they leave to scour the surrounding sky for sustenance.

But that isn’t the astonishing part.

A sign near the sinkhole viewing platform mentions a top-secret, World War II weapon called “Project X-Ray.” When I asked our guide about the undertaking, he smiled. “It lost out to the Manhattan Project,” he said, and then shared the tale.

On December 7, 1941, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, a Pennsylvania dental surgeon named Lytle S. Adams was visiting Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico. As the implications of Japan’s act began to sink in, Adams’ thoughts turned to retaliation.

Adams was amazed by the hundreds of thousands of bats that emerged from and returned to the caverns every night.

He wondered if they couldn’t be used as weapons—fitted with incendiary devices and dropped from planes. He had heard that many of the buildings in Japanese cities were constructed of wood and realized that if bats could be “weaponized,” they could be released to roost before sunup, when built-in timers would ignite the incendiaries, creating thousands of fires simultaneously.

On January 12, 1942, Adams communicated his thoughts to the White House by letter. Adams’ idea made it to President Franklin Roosevelt’s desk, and within days, Roosevelt had dispatched instructions regarding the plan to an Army colonel. “This man is not a nut,” Roosevelt wrote. “It sounds like a perfectly wild idea but is worth looking into.”

The “bat bomb” project was soon off the ground, and the effort appeared promising. Bats generally congregated in large numbers, could carry twice their weight in flight, would fly in darkness and roost in secluded places and, perhaps most important, could be manipulated to hibernate and, while dormant, did not require food or maintenance.

Adams himself was recruited to research and acquire a suitable species and sufficient numbers of bats. By March 1943, the Mexican free-tailed bat had been chosen for the operation, and military napalm inventor Louis Fieser was designing miniature incendiary devices for the bombers. The bats were being collected from large caves in Texas, including Devil’s Sinkhole and Bracken and Ney caves, and Carlsbad Caverns.

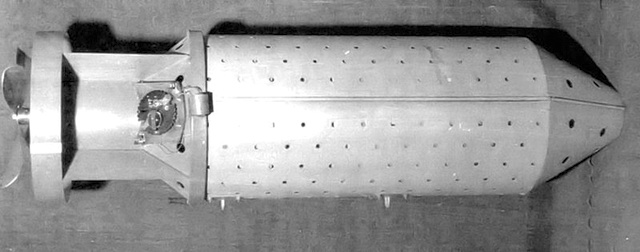

In early May 1943, 3,500 bats were tested at Muroc Dry Lake in California. First they were placed in refrigerators to force them to hibernate. Then on May 21, 1943, a test run involving five large canisters of bats was executed. Each canister held cardboard boxes packed with around 180 bats, which were supposed to exit as they awoke from hibernation. The bats were dropped from 5,000 feet, but the canisters descended too quickly. The bats never took wing because they had not fully recovered from hibernation.

The project was relocated to a new auxiliary airfield under construction at Carlsbad, New Mexico, and the experiments continued. In the next test run, the bats were placed in ice cube trays to facilitate hibernation, then fitted with dummy incendiaries and positioned in cardboard cartons for the drops. Unfortunately, when the next batch of bats descended from a B-25 and a Piper L-4 Cub, many, again, didn’t recover from hibernation quickly enough.

Undeterred, project team members gathered more Mexican free-tailed bats and tried again. This time, they allowed the bats more time to recover from hibernation before they were deployed, and many woke up too quickly and escaped from the cardboard cartons.

Testing continued with mixed results. By early June, the Mexican free-tailed bombers had burned down the new Carlsbad Airfield’s control tower, a barracks and several other buildings, all while in various stages of construction. A report dated June 8, 1943, indicated that work on the project had concluded until researchers developed better incendiary device attachment mechanisms, a special time-delay, a parachute-delivered bat container (to allow them more time to shake of the effects of hibernation) and a less complicated time-delay igniter to activate the incendiary payloads.

In August 1943, the project was passed on to the Navy and assigned to the Marine Corps. This is when the program became known as Project X-Ray.

Marines began guarding Devil’s Sinkhole and the other major bat caves in Texas. The experiments recommenced at the Marine Corps Air Station in El Centro, California, on December 13 using improved egg crate bat trays in the bomb canisters. After numerous experiments and operational tweaks, a definitive test mission was executed over a mock-up Japanese village at the Dugway Proving Grounds test site in Utah.

An incendiary specialist at Dugway reported that the bat bombers were effective because the small units were capable of creating a reasonable number of destructive fires without being detected. A National Defense Research Committee observer concurred, concluding that Project X-Ray had indeed produced an effective weapon.

After some positive results and optimistic accounts, more advanced and effective incendiary devices were ordered and an expanded Project X-Ray test regimen was scheduled for August 1944. But by then, Project X-Ray was racing against the Manhattan Project, and when Navy Fleet Adm. Ernest J. King was informed that the bat bombers would probably not be combat ready until mid-1945, he canceled the project. The bat bomb project had cost an estimated $2 million.

For Mexican free-tailed bats, the war was over. The Marines left the Texas caves, and normality returned to Devil’s Sinkhole.

Today the descendants and relatives of the former kamikaze bat bombers of Project X-Ray no longer have to worry about being placed in refrigerators or egg crates. Like their mammalian brethren in the U.S. Camel Corps, some bats did their bit and then the rest went about their business. Bat-watching in places like the Sinkhole, the Ann W. Richards Congress Avenue Bridge in Austin and Clarity Tunnel at Caprock Canyons State Park afford bats some level of celebrity—but now as natural wonders instead of weapons.

——————-

E.R. Bills is a writer from Aledo.