In October 1918, El Pasoans couldn’t congregate in public places, go to school, church or the theater. They were even required to wear face masks in public. Even with such precautions, by the end of the year, 600 citizens were dead. Was it the bubonic plague, scarlet fever, an early strain of Ebola? It was none of those infamous killers—it was the flu.

The 1918 influenza, also called the Spanish flu, killed at least 50 million people around the globe. That’s a conservative estimate; experts such as Alfred W. Crosby, professor emeritus of American studies, history and geography at the University of Texas, say the number may be more like 100 million. The deadliest virus ever known took El Paso, a West Texas town of 75,000, by storm.

El Paso had some factors that made it especially susceptible: a large population with a dense urban core; overcrowded Mexican-American neighborhoods that did not have hospitals or other health services; and Fort Bliss, which housed soldiers in close quarters, many of whom had recently returned from Europe where the flu had already taken hold as fighting raged in the battles of World War I.

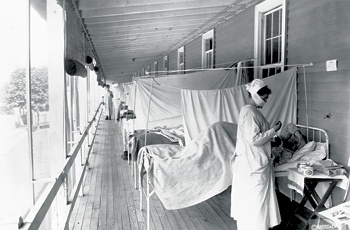

El Paso historian Fred M. Morales wrote about the city’s oldest neighborhood, Chihuahuita. He said that ambulances had to come to the area four to five times a day to transport the ill and dying to makeshift hospitals.

On November 9, the ban on public gatherings was lifted; two days later, more than 8,000 people came out for the Armistice Day parade. The virus had run its course, and the Great War was over.

Commemorating the end of a war is always bittersweet, even for the victorious, tempered by respect for those who died in service. In 1918, an aching irony marred the celebrations as many young men returned from war only to be stricken with the flu. It killed swiftly, in a matter of days, and proved most deadly for those aged 20 to 40. In fact, this strain of influenza killed more Americans in one year than had died in battle during the war.

Crosby published harrowing accounts of the illness in his 1976 book, Epidemic and Peace, 1918.

But until the mid-1970s, this killer was largely unknown by those born after 1918. Families, for the most part, didn’t pass down stories about it. Historians didn’t tell its tale. Yet it was the single biggest worldwide pandemic ever.

Why was the story of this frightening illness so slow to emerge from the shadows of history? For those who lived through 1918, the war and the flu are inextricable from each other. Both brought death to the young and healthy. Perhaps those who lived through this terrible time didn’t tell its tales because they wanted to forget.

For some time, Crosby’s book was the only one written specifically about the epidemic. Largely ignored in its first edition, the book was revised for a 1989 edition, titled America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918, as viruses such as HIV/AIDS, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome or “bird flu”) and Ebola began to appear in headlines. Other researchers thought that the tragedy of 1918 might give us knowledge to stave off a future epidemic, and public health officials began planning for one. We can only hope that swine flu will not reach epic proportions.

In 1918, families were overwhelmed, sometimes losing several members within days. Judy Shubert, a Texan who writes family history pieces, knew the flu had affected her family but didn’t know how until she found some old letters. Her Great-Aunt Lucy died of the flu while traveling. Lucy’s parents, living in Millsap, received this devastating letter from a family friend she was visiting:

“Dear friend it is with a sad, sad heart, one that is broken—broken to tell you that we laid your darling at rest with our darling boys all in one lot and at the same time, Jan. Sat. 4 at 3 o’clock. Lucy died Dec. 30 and my little darling baby went home Dec. 31, and my two boys went New Year’s day. O you can’t know how hard it was to give up three at once and a true friend, too. All that loving hands could do was done. They all looked like they was asleep and so they were in the arms of our savior. We can’t understand why the Lord does these things but he will make all clear some day.”

The double blow of “the war to end all wars” and history’s deadliest illness left a wake of devastated families across the globe—families who, for the most part, didn’t pass down the stories of their tragedy. It didn’t matter how death came; its finality silenced a generation.

——————–

Shannon Oelrich, former Texas Co-op Power food editor, is a freelance writer who lives in Pflugerville.