Granger’s City Hall is normally a quiet place. Its single spire can be seen from a distance, marking the corner where the town’s daily business takes place. Columned archways, transom windows and pressed-tin ceilings are reminiscent of a time more than 100 years ago when cotton was king and the area prospered. Following that era, this quaint little town of nearly 1,300 settled into a predictable, comfortable routine.

But that all changed when Paramount Pictures transformed the quiet community into the backdrop for a new adaptation of the 1969 classic film “True Grit” starring John Wayne.

In October 2009, first-term Mayor Scott Murrah found himself in the middle of a major challenge when Paramount’s scouts visited Granger and told him that the town was being considered for the film’s location site. “I really did not grasp the full reality of how big that was going to be,” he said.

Two months later, after considering eight states and dozens of towns, Paramount gave Murrah the news that this predominately Czech community, nestled among the gently rolling blackland of Williamson County, would be getting company—Holly-

wood was, indeed, coming to this once-renowned railroad town.

Although Murrah realized that “True Grit” would generate much-needed revenue, bringing the movie to Granger would also mean disruption of the locals’ routine—and it meant making sure the town was back to normal by May 8, in time for the 33rd annual Granger Lakefest.

But the biggest concern for Granger officials was getting assurance that the historic bricks of Davilla Street, which were laid in 1912, would not be damaged during filming. Paramount officials gave that pledge, Granger’s City Council approved the project, and construction of the movie set began in January 2010.

Granger, which originated in 1882 when the Houston and San Antonio branches of the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad intersected, rolled out the figurative red carpet for Oscar-winning filmmakers Joel and Ethan Coen and a cast of some of the silver screen’s finest.

In the Coen brothers’ version of “True Grit”—a closer adaptation of Charles Portis’ novel than the 1969 production—Jeff Bridges plays the part of the salty, drunken and trigger-happy U.S. Marshal Rooster Cogburn. Matt Damon brings to life LaBoeuf, a self-serving Texas Ranger who has no reservations in “paddling the backside” of the gutsy 14-year-old Mattie Ross, played by newcomer Hailee Steinfeld. Josh Brolin’s character, outlaw Tom Chaney, rounds out the list of colorful characters for the blockbuster film that earned 10 Academy Award nominations.

Robbie Friedmann, Paramount’s location manager for the film, said the Coen brothers wanted a town that resembled Fort Smith, Arkansas, back in 1875—the central setting for the book and the movie. Granger had the necessary core elements required to make the period piece believably authentic.

“Granger was the town that time forgot,” said production designer Jess Gonchor, explaining that one of the town’s key attractions is a train crossing that helped set up a crucial scene.

“You have to sense that Fort Smith is the last stop on the line as Mattie arrives on the train.”

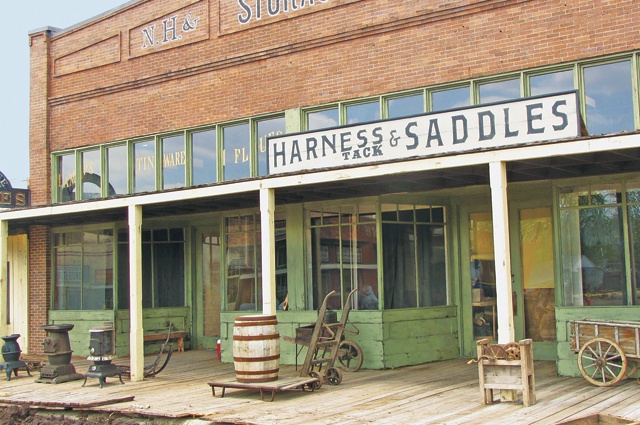

The movie required several “new” building façades, dirt streets and hitching posts. Six inches of dirt covered Davilla Street; Granger National Bank housed the marshal’s office and an attorney’s office. An abandoned building across from the bank was converted to the undertaker’s shop, and Granger’s main thoroughfare became a temporary home for businesses like Arkansas Laundry, Hotel Main and Pony Express.

Electric lines, once hovering overhead, were buried; any evidence of the 21st century was slipping away.

When scenes required trees where there were none, movie crews drilled holes into wooden poles and inserted makeshift “branches,” using a bit of movie magic and a bark-like covering to produce the desired effect.

The Monarch Boarding House façade was constructed in the lot next to the home of third-generation Grangerite Bennie Bartosh. He says he “watched every nail go in” from a bench in his backyard.

Paramount used golf carts to shuttle employees and customers, allowing businesses to remain open; and as visitors flocked to town to catch a glimpse of the Coens and the actors, merchants began to realize financial benefits.

The Cotton Club, a popular restaurant and dance hall, normally is open only on weekends for dinner, but owner Jill Cox changed her schedule to serve the famished crews home-cooked meals of chicken fried steak, mashed potatoes, fresh vegetables and gooey, rich desserts. “We fed 25 or 30 people every day for lunch, so it was very profitable,” she said.

Granger Lumber Company owner Walt Peters saw daily revenue increase by nearly $300, and Monica Stojanik, manager of Bohuslav’s Red & White Grocery—where circus peanuts and orange-slice candies hang from a wire rack—said hungry crews and visitors bought snacks and sandwiches every day.

Granger, Stojanik said, became a 24-hour tourist attraction: “On weekends, our little town had wall-to-wall crowds. We were all friends because we had a common interest. It was great for business and great for the community.”

Fittingly for the old railroad town, a vintage steam train brought in for filming was a major attraction. Movie train coordinator Stan Garner said he moved this same train to New Mexico for the movie “3:10 to Yuma” and to Marfa for “There Will Be Blood.” On the set in Granger, the first train sequence is short but critical, Garner says, because the train is used as a “reveal”—it’s the first time the audience sees Fort Smith.

Granger Police Chief David Mace, a soft-spoken man light years removed from the surly character of Rooster Cogburn, kept daily onlookers in line with the help of area law enforcement officials. Visitors were asked to be silent during filming, remain in designated areas and refrain from using any camera equipment.

In four short months, Granger had been chosen, transformed, filmed and returned to normal. Throughout the excitement, traditional priorities remained intact. True to its word, Paramount finished filming by May 8, in time for Lakefest. “Fort Smith, Arkansas” was gone, and Davilla Street, once again, belonged to the citizens of Granger.

Gone but not forgotten, the making of “True Grit” left an indelible impression on the rural community; residents felt ownership in the movie that briefly placed their town in the limelight. Now, there’s nothing out of the ordinary to observe, and Bartosh is one of many who feels the loss: “It was nice when they were all here—town seems empty now.”

Today, it’s business as usual at Granger National Bank, which served as Steinfeld’s classroom. As the youngest member of the cast, Steinfeld not only had to learn to shoot a gun, get comfortable with Western-style horseback riding and learn to roll a cigarette—she also had to keep up with her math lessons. When the movie wrapped, bank employees asked Hailee to autograph the boardroom wall—a permanent reminder of the newcomer who won the hearts of an entire town.

The film’s crew members left with their own fond memories. Garner recalls a little girl in a pink dress who came with her grandfather to see the steam engine. Fascinated, she picked up a railroad spike, sat down in the dirt and started playing. “Before you know it, her little pink dress wasn’t so pink anymore,” Garner recalls. “Those are the things I remember.”

Hollywood has moved on, leaving the townspeople to their simple, quiet lives. One blinking red light slows travelers and locals. With the exception of Ace’s Bar, nothing much is taking place in the way of nightlife. But when the weekend arrives, The Cotton Club, once again, will be in full swing, breathing life into Granger—a town that has survived the hands of time and has proven to possess a true grit of its own.

——————–

Connie Strong is a freelance writer based out of Chappell Hill, near Houston.