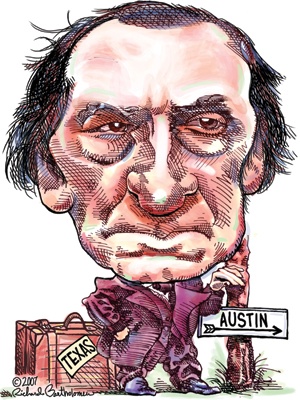

Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar probably deserves better from history than he gets.

Lamar was the first vice president and the second president of the Republic of Texas. A poet who was passionate about education, he is known as the “Father of Texas Education” and the “Poet President.”

While president, he moved the government from Houston to Austin because he believed the Republic’s capital should be more centrally located. During his term, Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Great Britain diplomatically recognized the Republic of Texas, and the Texas Congress passed a law benefiting schools and universities by setting aside land that could be sold only if the profits went to public education.

As president, Lamar also experienced failure. He never “solved the Indian problem,” and the Comanche continued to raid settlements. Lamar was responsible for a battle in Van Zandt County in which many peaceful Cherokee died, including Sam Houston’s good friend Chief Bowl. Desperate for money for his debt-ridden government, Lamar decided to annex the settlements around Santa Fe and Taos, in present New Mexico. He sent an expedition to Santa Fe in 1841, but Mexican troops captured all 275 soldiers and volunteers, marched them to Mexico City, and imprisoned them. History, as it often does, has taken note more of his failures than his successes.

History has also left Lamar overshadowed by Sam Houston, once his colleague and finally his archenemy. Houston was colorful and often loud; Lamar was quiet and soft-spoken. Houston dressed flamboyantly in moccasins and buckskins; Lamar was always carefully dressed, although he was known for baggy pants.

The two men became comrades when Lamar joined the Texas army as a private. A native of Georgia, he first visited Texas in 1835, when revolt against Mexico was brewing. His friend James W. Fannin urged him to travel around the territory, collecting letters, stories and official documents. Lamar meant to write an official history of Texas, but he never completed it. His notes, known as the “Lamar Papers,” are in the Texas State Library, where they are valuable to scholars.

Lamar decided to move to Texas and returned to Georgia to put his affairs in order, but when he heard of the massacres at the Alamo and Goliad, where his good friend Fannin died, he returned to Texas so fast that he rode his horse to death and had to finish the trip on foot. Lamar found Houston’s troops at Groce’s Ferry (outside present-day Houston) where they were training for battle. He so impressed Houston with his bravery, rescuing a young soldier about to be killed by Mexicans and rushing a crowd of Mexican soldiers surrounding Texas Secretary of War Thomas Rusk, that Houston promoted him to full colonel. Lamar and Houston disagreed after the Battle of San Jacinto and capture of Santa Anna. Houston believed Santa Anna was more valuable to Texas alive than dead; Lamar thought he should be executed on the spot. Houston prevailed.

In September 1836, Houston was elected president of the Republic and Lamar vice president. Houston favored statehood; Lamar did not. Houston, who had lived with the Cherokee, fought for recognition of the Indians’ rights to land in East Texas granted them by Mexico; Lamar believed the Indians had no rights.

According to the Constitution, Houston could not succeed himself after his first term. When Lamar announced his candidacy, Houston endorsed other candidates, two of whom died before the balloting. Desperately, at the last minute, Houston endorsed a candidate unknown to the voting public. By then, although Houston was personally popular, his policies had lost favor, and Lamar won the election. At Lamar’s inauguration, Houston spoke for over three hours, praising his own accomplishments. Lamar left in disgust, and an aide read his remarks. Lamar later delivered them personally to the Texas Congress.

When Houston was again elected president in 1848, Lamar retired. Long a widower, he traveled to Georgia with his daughter, Rebecca Ann, who died the following summer. He published his poetry in a book titled Verse Memorials, and the most poignant poems are elegies to his wife and daughter.

Judy Alter received the 2005 Owen Wister Award for Lifetime Achievement from Western Writers of America. She is a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power.