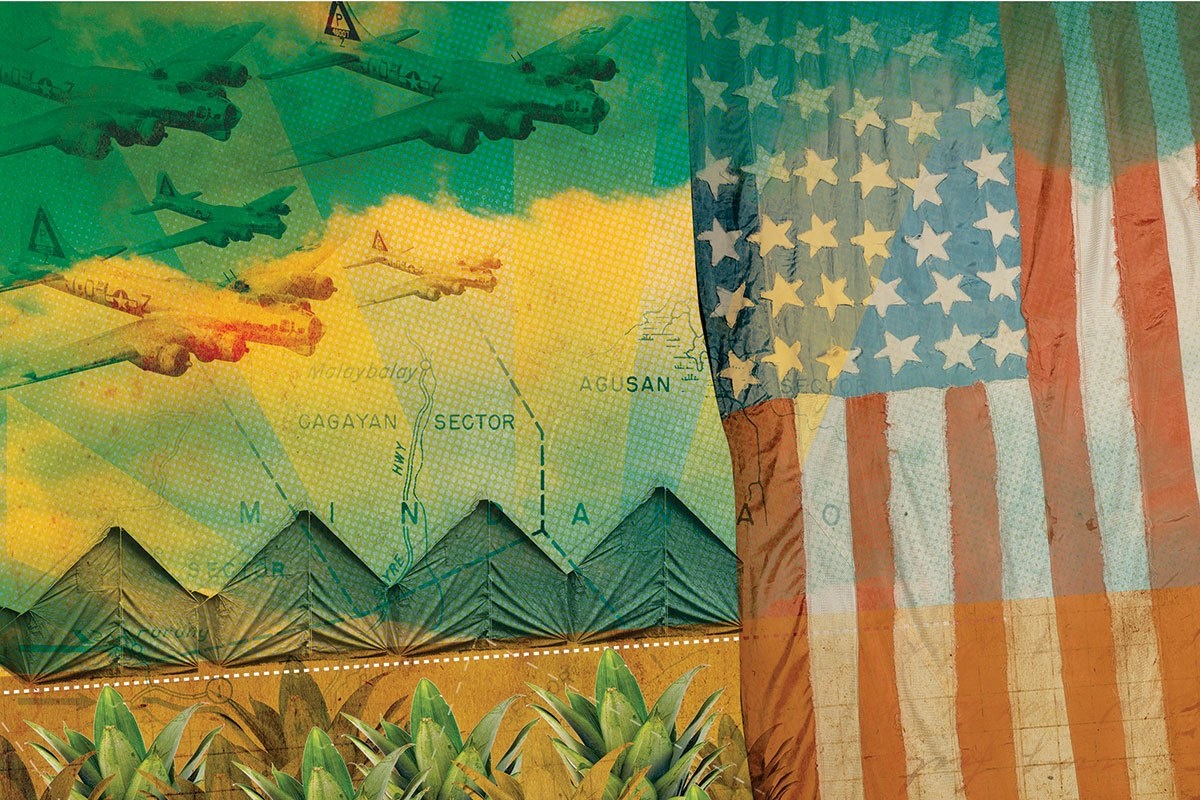

The most popular item in the shop at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg is a postcard depicting an American flag that is on exhibit in the museum. The flag was stitched together in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp by a Texas boy, Paul Ray Spain, and two fellow prisoners during World War II.

Spain was a 22-year-old farm boy from Olton when he joined the U.S. Army in Riverside, California, in September 1940. Like a lot of young men during the Depression, Spain dropped out of high school and joined the Civilian Conservation Corps. When he completed his CCC service, he enlisted in the Army rather than returning to his family’s cotton farm, hoping for adventure instead of backbreaking work.

He got more adventure than he bargained for.

In California, Spain was mustered into the 440th Ordnance Company, part of the ground echelon of the 19th Bombardment Group of the U.S. Army Air Forces. After training in Albuquerque, New Mexico, his unit was sent to San Francisco, and in October 1941, it boarded the USAT Willard A. Holbrook, a troop ship headed for the Philippines. Spain and his buddies in the 440th ended up at the remote Del Monte Airfield in Mindanao.

The airfield, built in the middle of the 12,000-acre Del Monte pineapple plantation in the fall of 1941, was a three-runway landing field for the long-range B-17 Flying Fortress bombers of the 19th, which was normally based at Clark Air Base on the island of Luzon. The field was so new that the men stationed there lived in tents; no barracks had been built when Spain and the rest of the 440th arrived December 3, 1941.

They accompanied 16 of the big B-17s that were flown from Clark Field to Del Monte; the rest of the 19th’s planes were destroyed on the ground when the Japanese bombed Clark Field on December 8. Nichols Field, closer to Manila, was bombed that same day, and Del Monte was suddenly the only operative large American air base in the Philippines. From December 18 to the first week of May 1942, the airfield was under constant air attack.

The B-17s on the ground at Del Monte were useless because there were no spare parts and little fuel, and they were flown to Darwin, Australia. Before the bombers left, Spain and his buddies dismounted some of the twin 50-caliber machine guns from the B-17 gun turrets and mounted them on tripods to create anti-aircraft batteries on the ground. Even though they shot down a few of the Japanese fighters escorting the high-altitude bombers, the guns could not reach the bombers themselves.

Del Monte Airfield withstood Japanese air attacks for 4½ months while the main Japanese army was occupied trying to dislodge the combined American and Philippine forces from the Bataan Peninsula, across the bay from Manila.

Early in January 1942, Gen. William Sharp arrived at Del Monte with a small force to organize the defense of Mindanao, and he made the airfield his headquarters. He asked the men of the 440th to help repair his troops’ weapons and make anti-tank mines by filling pineapple juice cans with dynamite and improvised detonators.

Del Monte Airfield became the last exit from the Philippines. In mid-March 1942, Gen. Douglas MacArthur and his family and staff evacuated the island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay and spent two nights at Del Monte. Next they flew to Australia in three B-17s sent from Darwin. A week and a half later, Philippine President Manuel Quezon and his entourage stopped at Del Monte on the way to Australia. Quezon’s son, Manuel Jr., wrote in his memoirs that there was “an overpowering smell of rotting pineapples, because no one was picking the fruit.”

On April 12, Gen. Ralph Royce arrived with 10 B-25 and three B-17 bombers to attack Japanese positions in the region as a prelude to Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle’s raid on Tokyo.

Japanese troops finally landed in northern Mindanao on May 3, and Del Monte Airfield, just 10 miles from the coast, was quickly overrun. Before the formal surrender, the post commander gave the American flag that flew over the field to Spain, by now a corporal, and two other members of the 440th, Privates Joe Victoria and Edwin Lindros. His order was for them to burn the flag to keep it from falling into Japanese hands. They complied, but before setting fire to the flag, they cut the 48 stars from its field and hid them in their clothing.

Miraculously, the three men managed to stay together through 40 months of Japanese captivity. They were first taken to Davao Penal Colony on the southeast coast of Mindanao, where they remained for two years, and then in June 1944, Spain, Lindros and Victoria were loaded into the holds of Japanese freighters—the notorious “hell ships”—and taken to Japan.

At war’s end, the three men were in Nagoya Prison Camp No. 7 in the city of Toyama, where they were beaten, starved and forced to work 12 hours a day in a steel mill. On August 22, 1945, a week after Emperor Hirohito’s announcement that Japan would surrender to the Allies, guards told them the war was over.

Spain, Lindros and Victoria retrieved the stars they had hidden for 3½ years in the steel mill. Using an old sewing machine and a rusty nail, they sewed the stars onto a 4-by-6-foot American flag they made from parachute silk. They hoisted the flag over the camp gate, and it was flying there when American troops finally reached the camp September 7.

The three men agreed that when they got home, they would pass the flag among themselves as long as they were alive. “The deal was that one would keep it and then send it to the next one,” said Spain’s son, Greg.

Spain was the last survivor, and when he died in Austin in 1986, the flag was placed on his coffin and then given by his widow to the National Museum of the Pacific War.

Marty Kaderli, the museum’s director of membership and development, has been with the museum for 30 years. “Because the prisoners of war made it a symbol of not surrendering,” she says, “it is the most visited and revered item in the museum’s collection.”

——————–

Lonn Taylor, former historian at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, lives in Fort Davis. He is the author of The Star-Spangled Banner: The Flag That Inspired the National Anthem (Harry N. Abrams, 2000).