When world-renowned French rock art expert Jean Clottes visited the Lower Pecos Valley in 2006, he was stunned by the rock paintings he saw in the caves and limestone shelters there. “It is my considered opinion—after having seen rock art on all the continents—that the Pecos River rock art is second to none and ranks among the top bodies of rock art anywhere in the world,” he said.

He could have said the same thing about the Hueco Tanks State Park and Historic Site northeast of El Paso. Together, the two areas in West Texas offer a fascinating glimpse into the beliefs and preoccupations of early inhabitants who lived here or traveled through over the millennia.

You can see these paintings on guided interpretive tours offered at both sites (see “Rock Art Tours” sidebar). In the Lower Pecos Valley near Del Rio, you’ll see large polychromatic panels that depict the shaman’s journey to the spirit world. At Hueco Tanks, you can see some of the more than 5,000 mysterious images, including the largest collection of painted masks in North America. The paintings are hidden amid rocks that held caches of fresh water (these hollows are called huecos) that have attracted travelers and inhabitants for more than 10,000 years.

Although many scholars, such as Texas archaeologists Harry Shafer and Carolyn Boyd, have spent their careers unraveling the mysteries of these paintings, you can begin to decipher a few of the styles and symbols quickly. Here’s a primer to get you started.

HUECO TANKS

Chihuahuan Polychrome Abstract Style

Early Archaic period (possibly Middle Archaic)

The earliest Archaic paintings at Hueco Tanks consist of abstract wavy lines and comb-like designs in red and black. Human and animal figures are conspicuously absent. No Chihuahuan Polychrome Abstract Style figures have been directly dated, but some research- ers believe that these figures may have been painted as early as 5,000 to 8,000 years ago, during the Early Archaic period.

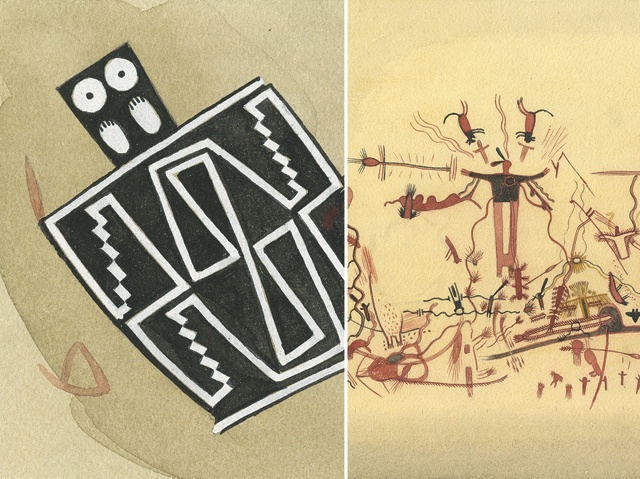

Jornada Mogollon Style

A.D. 650 to 1400, Late Prehistoric period

The Jornada Mogollon left behind more than 200 painted masks, many hidden inside caves. The late anthropologist Kay Sutherland theorized that the Jornada, who practiced agriculture, merged hunting-themed artistic motifs inherited from Archaic hunter-gatherers—horns and horned animals such as mountain sheep and deer—with Meso- american agriculture-themed imagery such as the jaguar, the plumed serpent Quetzalcoatl and the rain god Tlaloc. The Tlaloc figures at Hueco Tanks, for example, combine the goggle eyes of Mesoamerican tradition with the trapezoidal body of the Archaic tradition. Sutherland theorized that this new iconography developed at Hueco Tanks and later found its way to the kachina culture of Southwestern Indians. It can still be seen today in the art of the Hopi and other Pueblo people.

Historic Style

1800s, Historic period

Dancers and musical instruments, giant snakes, horses and soldiers are shown in panels that date to the Historic period. These images were probably largely painted by Mescalero Apache, with perhaps a few images by Kiowa or Comanche. The Tigua of Ysleta del Sur Pueblo also claim authorship of some of the imagery at Hueco Tanks. These historic paintings reflect the first early contact with Europeans in the area.

LOWER PECOS VALLEY

Pecos River Style

2250 to 800 B.C., Middle/Late Archaic period

Paintings in red, black, white and yellow portray the myths and rituals of the hunter-gatherers who lived in the region thousands of years ago. Some of the imagery depicts the shaman’s trance-induced journey to the spirit world. In these paintings, the shaman’s spirit is shown leaving his or her body. In some examples, the shaman takes the form of an animal, such as a bird, deer or panther. Birds and other creatures may escort the shamans on their journey or act as a barrier. Abundant ethnographic evidence—as well as the images themselves—suggests that sha-mans entered a trance induced by local hallucinogenic plants such as jimson weed, mescal beans or peyote.

Red Linear Style

Late Archaic period

The date for this style has not been firmly established. The one date obtained through radiocarbon dating places it within the Late Archaic period around A.D. 700. These tiny paintings depict human stick figures frenetically engaged in hunting, dancing and ritual activities. Some researchers have noted their stylistic similarity to Kokopelli, the flute player popular in Southwest- ern Indian iconography.

Red Monochrome Style

Late Prehistoric period

Large horizontal panels show silhouette images of humans with bow and arrows alongside animals such as dogs, turkeys, deer, rabbits, turtles and catfish. The human figures often have enlarged fingers and toes. Humans are always shown frontally, and animals are typically shown in profile. Most of the human handprints found throughout the Lower Pecos date to this stylistic period. Due to the presence of the bow and arrow in these paintings, archaeologists have determined that this rock art style emerged during the Late Prehistoric period around A.D. 800 following the arrival of bow-and-arrow technology in the region.

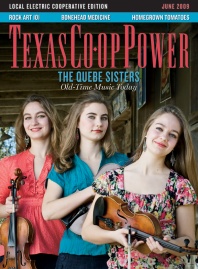

Historic Style

A.D. 1600 to 1800s, Historic period

After European contact, new subjects began to appear in the paintings—horses with riders, Spanish soldiers, churches, priests and guns. Explains Shafer in his book Ancient Texans: Rock Art & Lifeways Along the Lower Pecos: “Under pressures from Spanish and then U.S. expansion, the Historic Indian groups, mounted on purloined horses and armed with traded and stolen weapons, took refuge in the … uninhabited regions, such as the Lower Pecos and northern Mexico … These marauders of the southern Plains also left their artwork on the limestone canvas of the region. The topics they favored seem to reflect a growing familiarity with European culture.” Poignantly, the art also represents the beginning of their culture’s demise.

——————–

Elaine Robbins has written about mountain lions and butterfly gardens for Texas Co-op Power.