News stories about fraudulent internet-based land auctions in West Texas remind us that land fraud has been part of Texas life since the beginning of settlement here. In response to the modern-day scams, Jeff Davis County lawyer Bart Medley told a USA Today reporter that “much of the property was advertised with photos showing things like running water, green trees and green grass—things that simply don’t exist in that particular location.”

Medley’s words echoed similar ones spoken by Texas pioneer Noah Smithwick when he described a gang selling counterfeit Mexican land certificates to settlers coming to East Texas in 1831.

Both groups were peddling something that did not exist.

The biggest of all Texas land scams took place in the Big Bend, where everything is bigger, and it involved some bigger-than-life characters. At the heart of the story is Ben Leaton, a former scalp hunter who traveled north from Chihuahua City in 1848 with a woman named Juana Pedraza. Leaton moved his outfit into the ruins of an old Spanish fort on the north side of the Rio Grande about 4 miles downstream from Presidio del Norte (now Ojinaga, Chihuahua).

He transformed the ruins into a 40-room, walled adobe trading post, which he called Fort Leaton. There, he exchanged guns and ammunition with the Apaches for stolen livestock. John Caperton, who spent several days at Fort Leaton in 1849, described Leaton as “a remarkable man who had been all of his life in the moun-tains, knew nothing of government or law, was a law to himself.”

Gov. Angel Trias of Chihuahua, in a letter of complaint to U.S. Army Maj. Jefferson Van Horn about Leaton’s trade with Native Americans, called him a man “who does as he pleases, without respecting either the authorities of the Presidio or the laws of the country.”

Leaton’s fort occupied the only acreage in the river valley suitable for agriculture, and there were several Mexican farmers growing crops on it. Leaton dispossessed the farmers by paying Cesario Herrera, the alcalde, or mayor, of Presidio del Norte, to forge a title to the land for him.

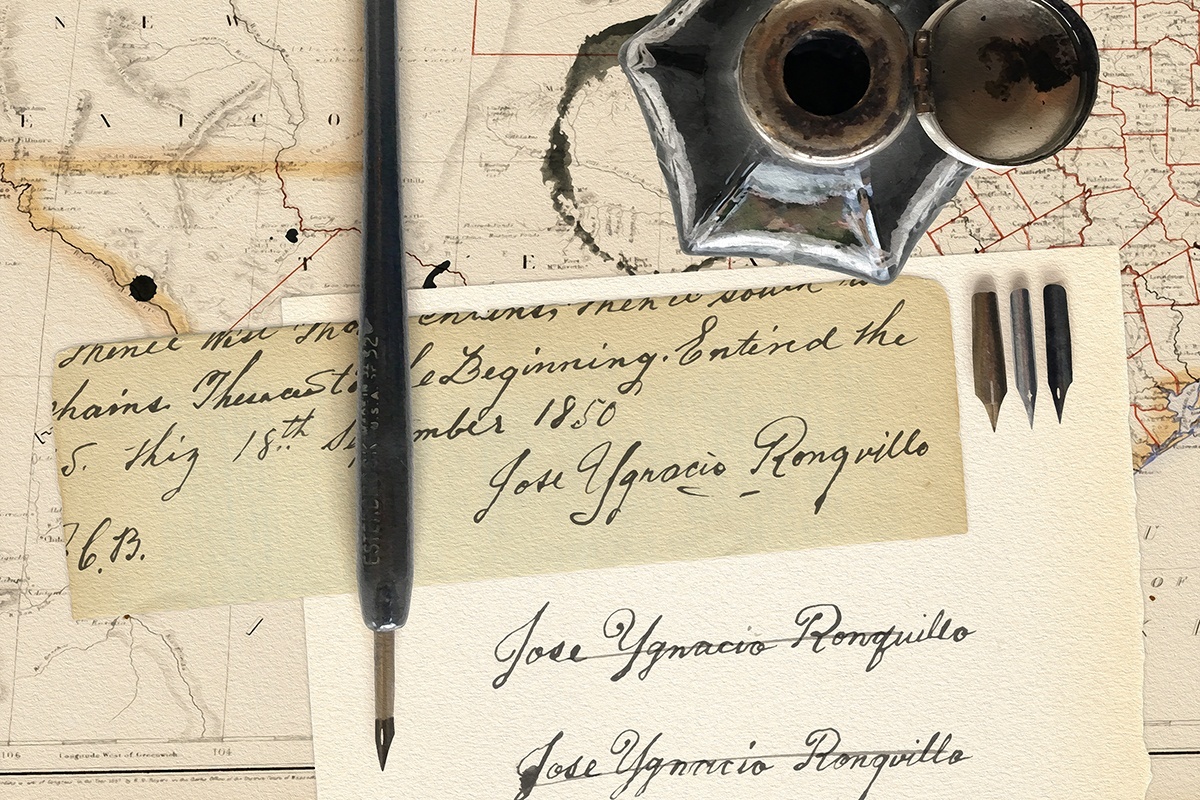

Then he convinced Herrera to forge a grant of 225 leagues (about 1 million acres) of land in what is now Brewster, Presidio and Jeff Davis counties. The grant was backdated to 1832 and purportedly made by Herrera to a Mexican army captain, Jose Ygnacio Ronquillo, who had been living at Presidio del Norte and had been killed in a battle with Apaches in 1834 or 1835. Herrera also forged field notes for a survey of the grant and a chain of title that involved transfers of the grant from Ronquillo to Hipolito Acosta and from Acosta to Pedraza, Leaton’s common-law wife. Herrera and Leaton were careful to ensure that all the people named in the forged documents, except Pedraza, were dead.

Leaton intended to have his million-acre grant confirmed by the Texas Legislature, but he died before he could complete the process, and his heirs failed to follow through on it. Everyone forgot about the Ronquillo Grant until 1884, when silver was discovered at Shafter, and the Presidio Mining Company opened a mine there.

Leaton’s grandson, Victor Ochoa, revived his family’s claim. A picturesque figure who inherited some of his grandfather’s characteristics, Ochoa launched a revolution against Porfirio Diaz from El Paso in 1893 and as a result ended up in the federal penitentiary in Brooklyn for violating the Neutrality Act. He invented and patented a streetcar brake, a fountain pen, an adjustable wrench and a flying machine he called an ornithopter, described by one writer as looking like “two bicycles being attacked by a pterodactyl.” Ochoa was also deeply involved in the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920.

David Romo, in his history of El Paso during that revolution, summed up Ochoa’s career by calling him a “revolutionist, federal prisoner, inventor, corporate president, writer, arms smuggler, narcotraficante, currency counterfeiter, secret service informant and mine owner.”

Ochoa hired Trevanion Teel, a flamboyant San Antonio lawyer who once won a murder case by swallowing the indictment and then challenging the state’s attorney to produce it, to sue the mining company for $1 million plus $6,000 a month rent.

While Teel was preparing his case, another claimant appeared, a Juarez attorney named Estanislado Ronquillo, who said that he was the grandson of Capt. Jose Ygnacio Ronquillo and thus the legitimate heir to the grant. Teel had attorney Ronquillo arrested for asserting a false land claim and was able to prove it in court. He demonstrated that even though Ronquillo’s grandfather was indeed named Jose Ygnacio Ronquillo, he had never been a captain in the Mexican army and had never lived at Presidio. Therefore, he was not the man to whom the grant had allegedly been made.

Before that arrest took place, however, the faux descendant had already sold his claim to James T. Fitzgerrell of Las Vegas, New Mexico, for $100,000. Fitzgerrell, in turn, sold two-thirds of his interest to Seth Crews of Chicago for $150,000, and then Crews and Fitzgerrell jointly sold the whole grant to Ernest Dale Owen, a Chicago investor representing something called the Chicago and Texas Land and Cattle Company, for the incredible sum of $4.5 million.

Owen bought Ochoa’s claim, which got Teel out of the way, and in 1892 filed suit against the Presidio Mining Company. The case ended up in the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans, and the testimony given there provides insight into conditions around Fort Leaton in 1850.

Depositions were taken from everyone who knew Leaton, Pedraza and Herrera. As historian Jefferson Morgenthaler puts it in his book The River Has Never Divided Us (University of Texas Press, 2004), “Owen got pounded at the trial. … Witnesses testified that Ben Leaton was a scoundrel, that Cesario Herrera had been taken to Chihuahua in shackles for forging land grants, that enormous land grants were illegal, that the conditions to the purported grant had never been met or waived.”

Jose Policarpo Rodriguez, a highly respected Methodist minister whose signature as chain carrier was on the field notes of the survey filed by Leaton in San Antonio in 1850, testified that he knew the surveyor whose name was on the field notes, R.A. Howard. Rodriguez said he carried the chain for Howard on many surveys, but that he could not remember walking around a 2,345.5-square-mile tract of land with him in the summer of 1850.

John W. Spencer, a neighbor and one-time business partner of Leaton’s, testified that even though the grant was supposedly made in 1832, no one around Presidio had heard about it until 1849. Victoriano Hernandez testified that he was 76 years old and had lived at or near Presidio all of his life, that he had first met Jose Ygnacio Ronquillo in 1824 and knew him well, and that he had not heard of the Ronquillo grant until long after Ron-quillo’s death. The court concluded, in Morgenthaler’s words, that “the Ronquillo land grant had been a scam from start to finish,” and Owen was left holding the bag for $4.5 million.

The theme of this tale is that it is possible to make money out of land anywhere in Texas if you can find the right sucker to pass it on to before the bottom drops out of the deal.

——————–

Historian Lonn Taylor writes from his home in Fort Davis.