Sidewalks to nowhere. Walls without roofs. Vacant hotels. Fallen trees. Graves. Seeing relics of abandoned towns along Texas highways, fields and railroads evoke questions about the past.

“There is just a ceaseless interest in this topic,” says T. Lindsay Baker, Tarleton State University history professor and Texas ghost town expert. “People connect with the dreams and the hopes of the people who once lived in the places.”

Baker identifies more than 1,000 former towns across the state in “Ghost Towns of Texas” (University of Oklahoma Press, 1986). Of the 88 sites he chronicles for the first of his two books on ghost towns, some still have skeleton populations or have been revitalized, he says, explaining that his definition of ghost towns are “places whose reason for being no longer exists.”

Guided by Baker’s definition, I explored four diverse sites, avoiding well-known destinations in favor of the obscure to sample why some Texas towns die. By visiting these places, I got to “see, smell, and touch Texas history where it was made,” as Baker implores the readers of his book to do. I learned history from the remains themselves—or lack thereof —and from the Texans who came from the dust, woods, mesas and pastures to share their stories.

Sher-Han

A series of cold calls leads to Hansford County Judge Benny Wilson to see whether he’s heard of long-gone natural gas company town Sher-Han in the Panhandle.

“I grew up there,” Wilson chuckles. “I didn’t know I came from a ghost town.”

Phillips Petroleum Co. founded Sher-Han, named for Sherman and Hansford counties, in 1944 to process natural gas from a southern Great Plains oilfield. The company was growing to support industries during World War II, according to the book, “Phillips The First 66 Years” (Phillips Petroleum Co., 1983). The Michigan-Wisconsin and Panhandle Eastern pipeline companies also set up compressor stations there.

Wilson’s father worked in the “Mich-Wish” plant, and the family rented a company-provided house on-site for $40 a month starting in 1959. The three companies provided a total of 105 homes, and Sher-Han’s population reached about 400 and supported a vibrant town.

Having no paved roads leading to town, Sher-Han boasted its own community centers, a Baptist church that straddled the Texas-Oklahoma border, a grocery store with a Phillips 66 gas station, and recreational areas, including a golf course with sand greens.

But the companies dismantled Sher-Han in the 1960s. “Most of the companies realized the liabilities of having families that close to something that explosive,” Wilson says. “They urged everyone—in fact, they gave a deadline—to get those houses out of there.”

All the houses were moved or abandoned. Wilson’s parents bought their house for about $1,500 and moved it to Guymon, Oklahoma. Like his co-workers, Wilson’s father then commuted about 15 miles on newly built roads to work at the stations, which still operate, served by North Plains Electric Cooperative, along with a helium plant.

This spring, Wilson, 64, made the trek from the Hansford County Courthouse in Spearman back to his boyhood home. He had not returned for decades.

“Even as close as it is, it’s out of sight, out of mind,” he says.

Where State Highway 136 intersects the Oklahoma border, howling wind and high-swirling dust obscure Sher-Han from the modern world. From eroded roads with faded speed-limit signs, Wilson points out curbless sidewalks that lead to crumbling foundations among fallen dead elms, upturned roots sprawling. Low grass overtakes the basketball court, and cacti the baseball field.

“Just everything you look at,” he says, “you think of someone you grew up with and wonder what happened to them.”

Nearby, a labyrinth of tanks, pipes and warehouses comprises a gas compressor plant that thrums much like it did more than 50 years ago. On the horizon, wind turbines tower over the flatlands.

“I guess everything has its time in history,” Wilson says, “but I’m proud that I got to grow up there because I had a lot of good friends.”

Manning

The smell of honeysuckle and pine floats on a breeze, and dewberries ripen in the sandy loam among the grasses in the Neches and Angelina rivers’ bottomlands. At present-day Manning in East Texas, a white two-story bed-and-breakfast framed by sycamore trees overlooks a 15-acre pond that brims with bass.

This bucolic scene belies its history as one of Angelina County’s largest industrial towns. Manning prospered starting in 1905 around a Carter-Kelly Lumber Co. sawmill, which capitalized on the area’s virgin longleaf yellow pine forest before coming to a sudden end.

During its prime, the sawmill planed millions of board feet of lumber a year, and a company town grew to support the business. The population reached about 1,500 before the mid-1930s, according to firsthand accounts in the self-published book, “Were You At Manning?” compiled by Robert Poland, 94. His father, Frank Poland, worked in the mill’s lumberyard.

The town bustled with businesses, hotels, two picture-show venues, a church, school, jail, train depot and commissary, where townspeople could spend their company-issued currency. The finest and only painted house belonged to mill manager W.M. Gibbs.

One January morning in 1935, according to newspaper articles from that era, a fire consumed the sawmill with a blaze that could be seen from miles away. Kester Stanley, who was about 12 years old and living in Sweet Gum Valley at the time, remembers hearing sirens over the pop and crack of burning sap.

Because most of the area’s pine forest was already cut, the company didn’t rebuild, and most of the townspeople moved away. Carter-Kelly Lumber Co. dismantled the homes—except the Gibbs house—and the remains of the charred mill were left to fade.

On the dam of the sawmill pond, Robert Flournoy, 72, begins a tour of the ruins. His father was the Manning schoolhouse superintendent who purchased the mill manager’s property in 1941. The Lufkin lawyer grew up in, and now owns, the Gibbs house, which he recently converted into the bed-and-breakfast, served by Sam Houston Electric Cooperative. Guests of the Mansion at Sawmill Lake can stay in the Whippoorwill Suites and fish the pond or hike around the ruins.

In a shady meadow that would have been the epicenter of Manning’s industry, aggregate mortar binds the worn-down stone and redbrick walls of the mill complex, including the sawmill building, planer and dry kiln, where the forest’s thick vines and spider webs thread the many cracks. Scraps of half-buried iron scattered in the grass mingle with abandoned farm equipment.

“It’s amazing how nature reclaims places,” Flournoy says. “We think we’ll be forever.”

Girvin

The mesas and West Texas sky seem closer than they actually are at U.S. Highway 67 and FM 11 in northeastern Pecos County. In this semiarid region, wisps of cirrus clouds cross the hazy blue sky over flat-topped mountains just as they have before and after the rise and fall of the 20th-century railroad town of Girvin.

Named for early rancher John H. Girvin, the town developed around a cattle-

shipping point on the former Kansas City, Mexico and Orient Railway constructed in 1912. As the town grew, a post office, general store, hotel, saloon, school and lumberyard joined the wooden depot and shipping pens by the tracks. Over the decades, people came to Girvin to work in myriad industries, including oil and electricity production, salt mining and farming.

In 1933 a new highway, U.S. 67, bypassed Girvin, and eventually the freight station closed and passenger rail service to the town ended, according to “Pecos County History” (Staked Plains Press, 1984).

Mildred Helmers, Girvin’s postmaster for more than 30 years, and husband Arno purchased the depot building from the railroad for $1,000 in 1956 and moved it to the highway. They lived there, operating a general store, gas station, the Girvin Social Club bar and later the relocated post office, until the mid-’80s.

“She is the only woman who has moved a whole town,” says daughter Arna Marie Helmers McCorkle, 62.

The Girvin by the railroad became obsolete, but the town about a mile away by the highway, also called Girvin, lived on. The last residents left new Girvin as recently as 2000, McCorkle estimates. Today, the club is an abandoned sun-scorched building with broken windows, a dismantled porch and a rusty corrugated metal roof.

“Now it’s a ghost town just like the other one,” she says.

At old Girvin, roofless concrete block-and-plaster walls mark the site of the Helmers’ first general store and residence. Next door, the western-style facade of an old store is feebly braced with 2-by-4s. Nearby, the rafters of a former gas station mingle with debris on the ground, and the bare windows in the upper-story walls yawn over silent railroad tracks.

On a postage stamp-sized cemetery lot with no gate, knee-high iron crosses adorn crude mounds of rock marking mostly the resting places of children. At the foot of a comparatively ornate tombstone for Asa Galloway, 1901-19, a century plant has died, tall stalk felled and leaves rotting. Out of its mulch grows a young verdigris-colored agave.

The 1930s-era schoolhouse is a bright spot among the ruins and blur of green mesquite. The pink brick school, where the father and uncle of rancher Snap Woodward, 49, attended classes, now serves as a voting location and a venue for the yearly Girvin reunion. In 2012, about 15 families at the reunion celebrated the town’s 100th anniversary.

“Girvin has lived its glory,” McCorkle says. “But those of us who were raised here will always remember the fun we had.”

Morris Ranch

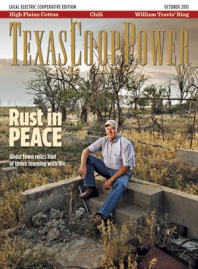

Wearing a sweat-stained cowboy hat and biting a Travis Club cigar, rancher William “Billy” Roeder, 71, leans on his truck parked along Morris Ranch Road southwest of Fredericksburg. He waits in the shade of a two-pronged live oak at the fence line of a former hotel that served guests of Morris Ranch, once a nationally known center for raising and training thoroughbred racehorses.

Francis Morris, breeder and owner of the filly Ruthless, who won the first Belmont Stakes in 1867, purchased 23,000 acres of Texas rangeland in 1856. He later hired his nephew Charles Morris to manage the equestrian complex. Morris Ranch reached its prime in the 1880s as a self-sufficient community entirely devoted to horses.

“They picked this corridor down here because they thought it was the best atmosphere, conditions, to raise horses,” speculates Roeder, who served as a director of the Gillespie County Fair & Festivals Association for 28 years and helped bring pari-mutuel horse racing to the county tracks.

Roeder, a Gillespie County commissioner, grew up on this land, and his ancestors were among the first settlers of Fredericksburg in 1846. His grandfather, whom he affectionately calls “Opa” after the German tradition, worked for the Morrises, whose horses raced in other states including New York and Louisiana. Opa Roeder’s job was to transport the horses via train to and from the racetracks.

The ranch’s decline began in 1895 after the death of Francis Morris’ son, John A. Morris, and the rise of a national movement to outlaw gambling that put most horse racetracks out of business.

When portions of the ranch went up for sale, Opa Roeder purchased 500 acres for $1 each. Roeder has preserved the slip of “yella notebook paper” that tallies his grandfather’s payments.

Having grown up on his ancestral land, the ruins of nearby Morris Ranch, now divided up and privately owned, are familiar landmarks to Roeder, and some harbor stories to which he is the last living connection.

“Once we’re gone, that generation isn’t going to know those people,” he says to longtime friend and fellow landowner Troy Ottmers, 57, of their children. Both men are members of Central Texas Electric Cooperative.

Roeder remembers the Morris Ranch hotel that served as a post office and general store where he, young and barefooted, would buy penny bubblegum in the 1950s. He attended several grades in the nearby Morris Ranch schoolhouse, a three-room limestone and gabled beauty with a bell and steeple.

Across a field where horses once thundered over a 1-mile training track, Roeder points out the roofless jockey house. Nearby, a hole in the ground marks the site of the former cotton gin. Towering above, limestone masonry forms a cylindrical building with a lookout deck, possibly a mill. The headquarters home, a frame two-story with wraparound porches, demonstrates the Morris fortune.

“For me, it’s neat to look at this and think of what this would look like if it was the 1880s,” Ottmers says, imagining bustling buggies and women wearing long skirts.

At the Hill Crest Cemetery, the oldest legible monument—a rose granite pillar flecked with chartreuse- and rust-colored lichen—memorializes William Morris, 1804–91, brother of the ranch’s original owner.

The cemetery’s high vantage reveals the scope of the former ranch. “As far as you can see—those mountains—was part of this,” Roeder says, nostalgic. “It was just yesterday. That ain’t a long time ago.”

——————–

Suzanne Haberman is a staff writer.