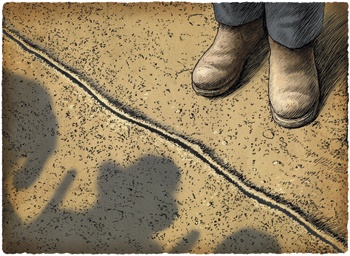

Of the many mysteries surrounding the battle of the Alamo, one of the most enduring and endearing centers on the line that Texas commander Lt. Col. William Barret Travis supposedly drew in the sand with his sword. According to the story that’s been passed down, Travis drew a line in the sand of the Alamo courtyard and asked any man willing to stay and fight with him to step across the line.

Oddly enough, the story of this line in the sand reportedly comes from the one man who chose not to step over it, a Frenchman and veteran of the Napoleonic Wars named Moses Rose. Rose was 51 at the time and his action, or inaction as the case may be, has been justified on the grounds that Rose had witnessed enough slaughter with Napoleon’s army that he wanted nothing more to do with such martyrdom. Asked later why he chose not to stay at the Alamo, Rose reportedly replied, “Because I did not want to get killed, by God.”

From that story, history has often tagged Moses Rose as “the coward of the Alamo.” Those who stayed perished at the hands of the Mexican army on March 6, 1836. While we might imagine that Rose hated the story of Travis’ line in the sand, that is not the case. In fact, the story comes to us courtesy of Rose, who told it often after he decided to get while the getting was good. Although the story of the line in the sand is doubted by some historians and scholars, the fact that Rose originated the story, portraying himself as something less than heroic in the process, adds a certain credibility.

Rose demonstrated some maturity and common sense in his escape from the Alamo. To the east of the Alamo was a dense mesquite thicket, which looked like the best way to get out, but Rose correctly surmised that such thickets would be thick with Mexican soldiers. Instead, he headed west, right through the heart of San Antonio, which was deserted, its citizens hiding behind locked doors. He saw not a single person on his way through town. He followed the San Antonio River south for about three miles, then turned east and made his way across the prairie toward Nacogdoches.

Rose stopped in Grimes County for a while and found shelter with the Abraham Zuber family. Mrs. Zuber picked cactus thorns from his body while he told her the story of Travis’ line in the sand. “Travis’ speech is burned into my soul,” he told her.

Had the story stayed with Mrs. Zuber we might not know anything of it today, but she repeated the story to her son, William Zuber, who had been with Sam Houston’s army when the Alamo fell. Zuber published the story in the 1873 Texas Almanac and later repeated it during an address to a Texas historical society in 1907.

According to Zuber, Moses Rose was with Napoleon’s army during its invasion of Russia in 1814 and fought gallantly enough to be named to the French Legion of Honor. He left France and ended up in Nacogdoches, where he was living when the Texas Revolution erupted.

Rose dedicated himself to the Texans’ cause, selling or mortgaging all his possessions to fight against the Mexicans—hardly the actions of a coward. He participated in the siege of Bexar and was present when Mexican Gen. Martín Perfecto de Cos surrendered. According to Zuber, Rose and Jim Bowie were close friends.

Moses Rose remains one of many enigmatic figures involved in Texas history, but the story he circulated about Travis’ line in the sand has seared its way into the American consciousness as a symbol of courage and patriotism. That story is the cornerstone of the Alamo legend itself.

J. Frank Dobie saw Travis’ line in the sand as more important than any discussion of whether or not it actually happened. “It is a line that not all the piety nor wit of research will ever blot out,” Dobie wrote. “It is a Grand Canyon cut into the bedrock of human emotions and heroical impulses.”

The man who first told the story went back to Nacogdoches and operated a butcher shop. He often testified on behalf of heirs of Alamo defenders trying to secure land grants for services rendered during the revolution. Whether or not people considered him a coward is not documented, but Rose moved to Logansport, Louisiana, in 1842 and died there in 1851.

Though Rose never married and left no direct heirs, a descendant of his brother Isaac presented Moses Rose’s musket to the Alamo museum in 1927. Rose might have used that musket at the Alamo but not, we are sure, for the entire 13-day siege.

——————–

Clay Coppedge is a regular contributor to Footnotes in Texas History.