It is hard for me to write dispassionately about J. Frank Dobie’s books because the first adult book I ever read was his Legends of Texas, first published in 1924. My grandmother gave it to me when I was 7 years old, and I devoured it. It was the first book I had ever read that referred to people I knew about.

Dobie’s uncle, Jim Dobie, who figures in several of the legends, once courted my grandmother’s little sister. Judge W.P. McLean, who hunted for Moro’s gold, was a family friend in Fort Worth. That book made the connection between life and literature for me. I moved on to other Dobie books, and my first adolescent writing efforts were bad imitations of Dobie’s tale-telling.

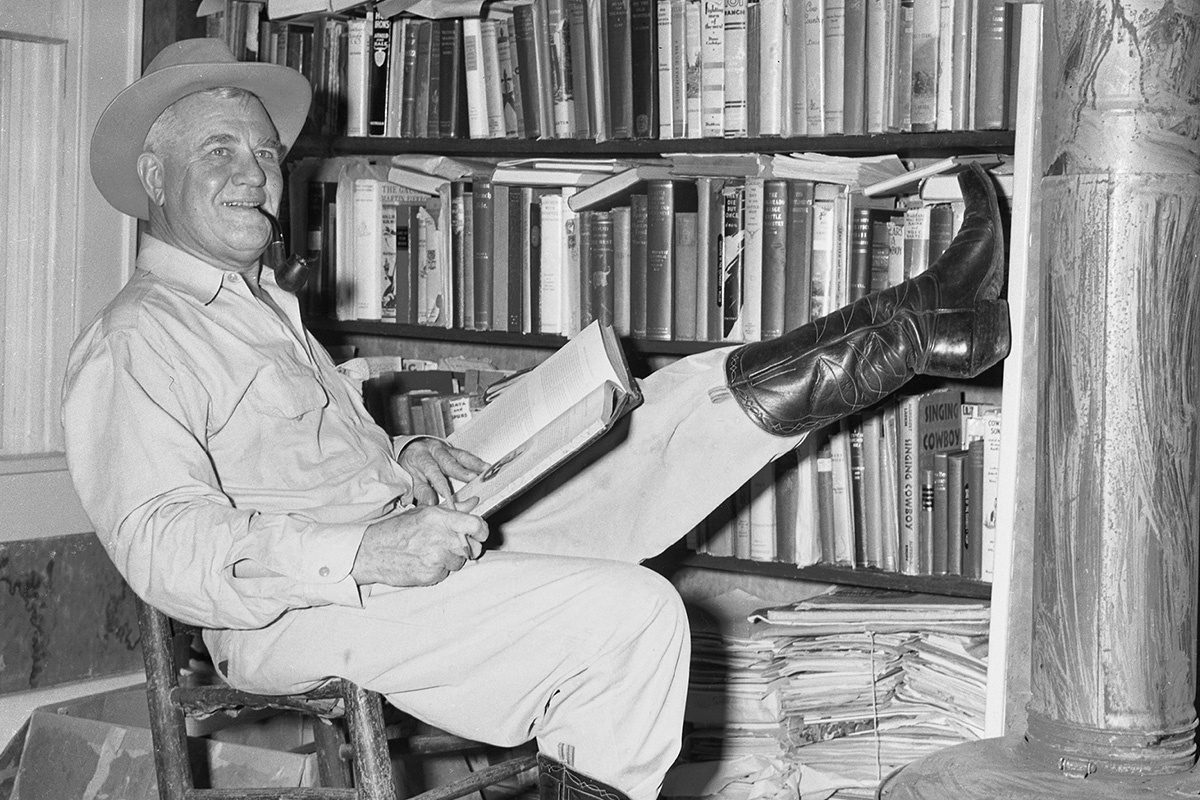

Although I occasionally saw Dobie on the Drag near the Universtiy of Texas in Austin, I never had the courage to walk up to him and introduce myself. By many accounts, he was a nice man, although Américo Paredes cruelly parodied him as the patronizing blowhard K. Hank Harvey in his George Washington Gómez, a novel written in the 1930s but not published until 1990, long after Dobie’s death. Stephen Harrigan paints an unflattering picture of him as Vance Martindale, a callow and ambitious English professor, in his novel Remembering Ben Clayton. In his 2009 biography, J. Frank Dobie: A Liberated Mind, Steven L. Davis traces Dobie’s intellectual development but says little about his personal life except that in 1919, when his wife, Bertha, was struck with the Spanish influenza, Dobie chose to remain with the peacetime Army in France, where he was enrolled in the Sorbonne, rather than apply for a transfer home to be with her. Davis quotes a letter that she wrote Dobie but never mailed, saying that he “cares a thousand times more for experience than for me.”

If I had to classify Dobie as a writer, I would have to put him with the regionalists, a group of American writers who flourished in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s and extolled the virtue of regional differences over mass culture and rural life over industrialism. They included Willa Cather, William Faulkner, Lewis Mumford, Robert Penn Warren, John Crowe Ransom, Mary Austin, John G. Neihardt, Bernard DeVoto, Zora Neale Hurston, Oliver La Farge and Mari Sandoz.

Many of these writers forged links to the emerging academic study of folklore and drew on material gathered by folklorists such as B.A. Botkin and Dobie’s friend John A. Lomax; some considered themselves folklorists. A few were utopians, attempting to formulate a culture based on American roots as an alternative to what they perceived as an alien European culture being disseminated from New York. All were antimodernists, wistfully clinging to an image of an older and apparently simpler America, the “sunny slopes of long ago” that Lomax and Dobie used to toast, the “old rock” that Dobie’s cattlemen heroes were cut from.

But Dobie was different from most of his fellow regionalists. They expressed themselves in fiction, poetry or, in the case of Mumford and DeVoto, essays and historical narratives, often based on folk sources. Dobie, as far as I know, never attempted a novel or published a poem. What Dobie excelled at was turning oral narratives into short written pieces. He had an ability to get people to talk, a sharp ear for cadence and language, and an uncanny ability to create a stage for his narrator. Most of his 20 books are, in fact, strings of finely crafted anecdotes derived from interviews with stove-up cowboys, prospectors and desert rats.

Dobie’s focus on oral tradition stemmed from his conviction that the narratives of old-timers had a value in themselves and did not need to be adapted into fiction or poetry to have communicative power. Literary historian Robert L. Dorman writes that Dobie saw their unadorned and unmediated words as artistic creations that contained truths about “the mind, the metaphor, and the mores of the common people” that escaped academic historians. Dorman says Dobie disdained the “Ph.D.s who could write historical learned monographs on ‘Utah Carl’ and ‘Little Joe Wrangler’ ” that would be full of “ethnological palaver” and would obscure the experience of hearing the singer or narrator “vivid and alive.”

Dobie’s A Vaquero of the Brush Country (1929) so closely paralleled the handwritten narrative of its subject, a retired cowboy named John D. Young, that many years after it was published, it became the object of litigation among Young’s heirs, the Dobie estate and the University of Texas, and it was reissued in 1998 with both Young’s and Dobie’s names on the title page as co-authors.

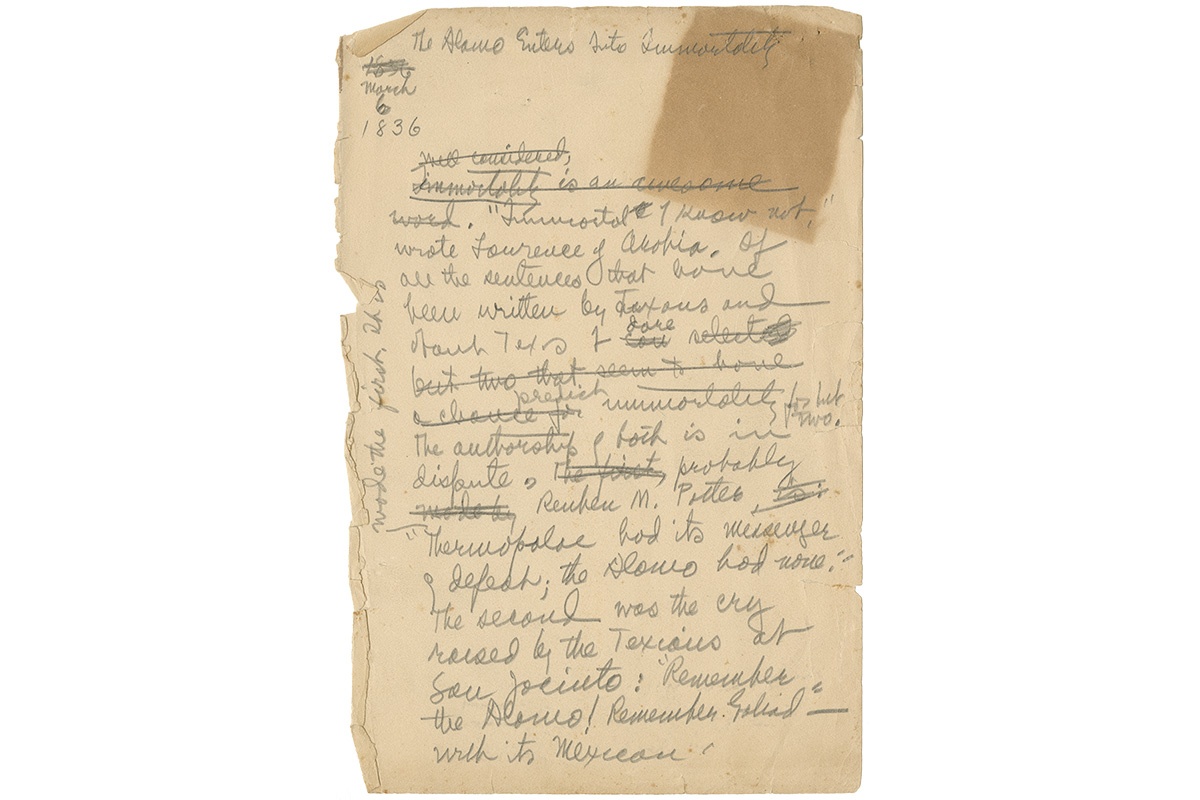

Much of Dobie’s popularity stemmed from being in the right place at the right time. The oil-rich state of Texas was attracting national attention in the early 1930s, preparing for the 1936 centennial celebration by shedding its southern former Confederate identity and assuming a new and dynamic one as part of the West, and Dobie wrote about ranchers and cowboys. When the centennial celebration came, Dobie was smack in the middle of it. He served on the Advisory Board of Texas Historians that reported to the Commission of Control for Texas Centennial Celebrations, got into a public dispute with the sculptor Pompeo Coppini about the Alamo Cenotaph, published The Flavor of Texas, and emerged as “Mr. Texas,” the state’s best-known spokesman. When the national spotlight shined on Texas, it illuminated J. Frank Dobie.

Dobie’s reputation declined after his death, reaching its nadir in Larry McMurtry’s ill-tempered 1981 denunciation of his books as “a congealed mass of virtually undifferentiated anecdotage: endlessly repetitious, thematically empty, structureless, and carelessly written.”

I don’t think he was as bad as all that. It’s true that he never wrote anything to equal Cather’s O Pioneers! or Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, but his books did make Texans, with their inherited cultural inferiority complex, realize that their native soil was fertile with literary inspiration, and they gave ordinary people a place in history long before “people’s history” became fashionable. Most of all, he knew how to tell a good story.

——————–

Lonn Taylor, widely published author and former historian at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, lives in Fort Davis.